chronopolis

︎Artist, Animation, Sci-fi, Technology

︎ Ventral Is Golden

chronopolis

︎Artist, Animation, Sci-fi, Technology

︎ Ventral Is Golden

︎ Ventral Is Golden

“There is a time for being ahead, a time for being behind; a time for being in motion, a time for being at rest; a time for being vigorous, a time for being exhausted; a time for being safe, a time for being in danger. The Master sees things as they are, without trying to control them. She lets them go their own way, and resides at the centre of the circle.”

- Tao te Ching.

“There is no clear proof that the city of Chronopolis did never exist. On the contrary, dreams and manuscripts agree in revealing that the history of the city is a story of eternity and desire. Its inhabitants, hieratic and impassive, have for sole occupation and sole pleasure to compose time. Despite the monotony of immortality, they live in expectation: an important event must occur at the encounter of a particular moment and a human being.

Now, this long awaited time is about to come..."

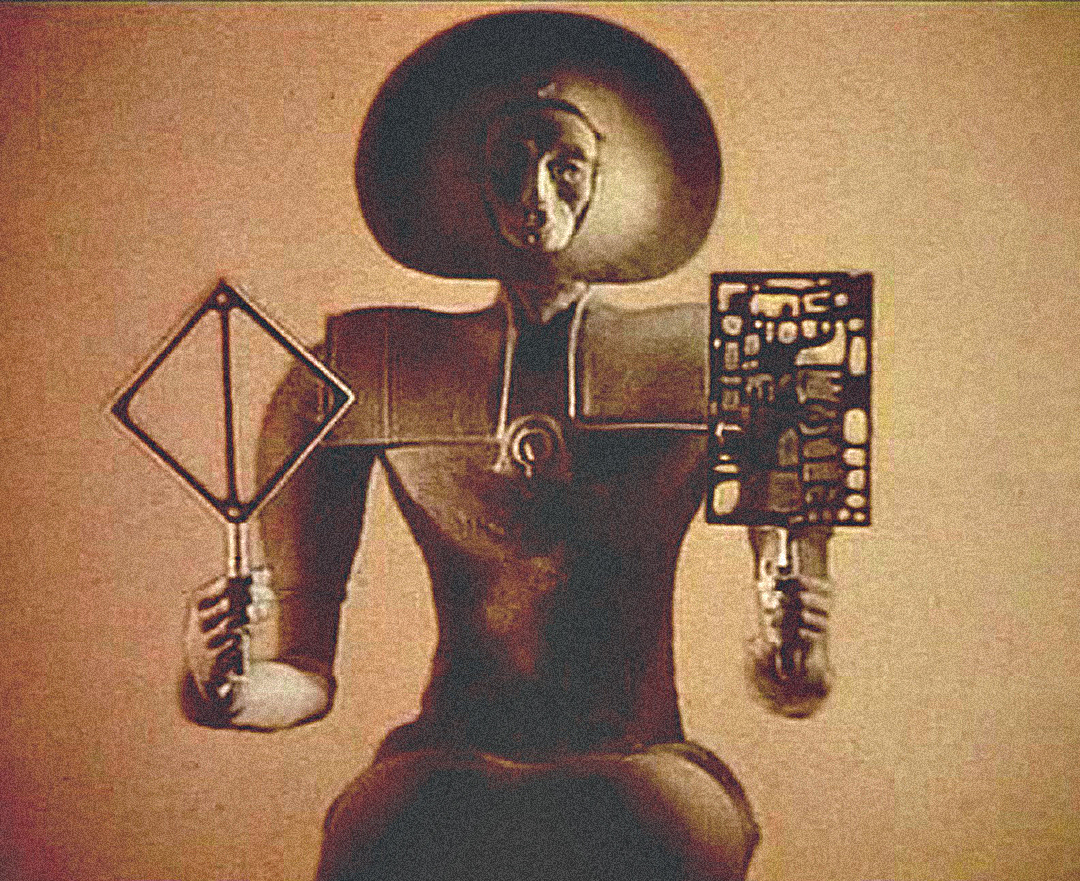

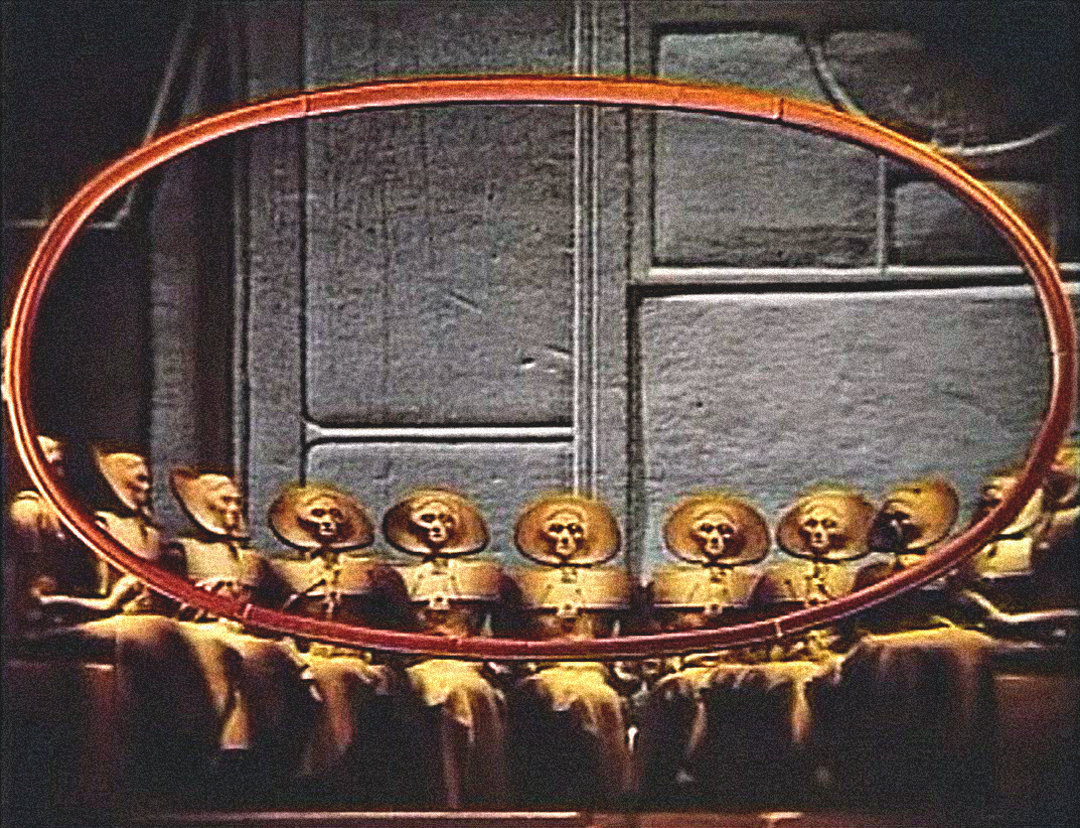

Chronopolis (1982), written, directed and produced by Polish artist Piotr Kamler, is an animated film that tells the story of an ancient city in the sky, populated by technologically advanced seers, who after acheiving eternal life have become jaded, finding that their most pleasurable pass-time and occupation is in the construction and dissolution of sentient mechanical devices.

Considered partly as a criticism of the films lack of an explicit narrative, Chronopolis in fact manages to avoid the more common science-fiction tropes by exploring instead the relationships between time and memory.

In part informed by the later musical score of its 1988 re-release by French experimental, electro-acoustic composer Luc Ferrari, and theories regarding the perception of time and the cinematic image of earlier french philosophers such as Henri Bergson and Gilles Deleuze, Chronopolis takes on an exploration of the boundaries of perception in relation to ‘duration’ and ‘intervals’ in acoustic and visual space.

Chronopolis (1982), written, directed and produced by Polish artist Piotr Kamler, is an animated film that tells the story of an ancient city in the sky, populated by technologically advanced seers, who after acheiving eternal life have become jaded, finding that their most pleasurable pass-time and occupation is in the construction and dissolution of sentient mechanical devices.

Considered partly as a criticism of the films lack of an explicit narrative, Chronopolis in fact manages to avoid the more common science-fiction tropes by exploring instead the relationships between time and memory.

In part informed by the later musical score of its 1988 re-release by French experimental, electro-acoustic composer Luc Ferrari, and theories regarding the perception of time and the cinematic image of earlier french philosophers such as Henri Bergson and Gilles Deleuze, Chronopolis takes on an exploration of the boundaries of perception in relation to ‘duration’ and ‘intervals’ in acoustic and visual space.

“It is time, 'a little time in the pure state', which rises up to the surface of the screen. Time ceases to be derived from the movement, it appears in itself and itself gives rise to false movements. Hence the importance of false continuity in modern cinema: the images are no longer linked by rational cuts and continuity, but are relinked by means of false continuity and irrational cuts. Even the body is no longer exactly what moves; subject of movement or the instrument of action, it becomes rather the developer [revelateur] of time...” - Gilles Deleuze.

In the historical traditions of Western philosophies, since Aristotle’s view that time was an unchanging and constant sequence of ‘nows’, to the Cartesian method of rationalising the world through the ‘Abstract Agent’ or the ‘Cartesian Self’ who was separate from time, firmly embedded the limitations of a future in which the material sciences described how bodies moved through uniformed space.

Across the topology of this psyche, the effects of time being perceived as its own substance had taken a secondary position in favour of the energetic exploration and exploitation of space.

Time, in this instance was perceived as being ‘taken by the soul’ in order to necessitate change, and became a phenomena defined mostly in relation to the measurement of the objects within it.

Ethnobotanist and researcher of the Eastern philosophy of the Tao te Ching and the I Ching, Terence McKenna, once wrote that “the Chinese looked not at the world of matter, energy and space, but the world of time, and carried out a very rigorous analysis of their own perception and discovered to their amazement that time is actually composed of elements.”

It was the basis of McKenna’s Time Wave Zero theory and his later computer program that mapped ‘habits’ and ‘novelties’ that ebbed and flowed throughout an historical time-wave. In much the same way as the Western Periodic Table of chemical elements describes bonding relationships of physical matter, the I Ching was a table that described the elements within the ‘Physics of Time’, articulated through symbols known as Hexagrams.

‘Chronos’, the Greek word from which everyday ‘modern’ time is conceived, is a measure of quantitative time, sequential and chronological, and necessarily extends through the Cartesian model of the “res extensa” and “res cogitans” - the Radical Dualism that became the engine house for the subsequent worlds built upon the material sciences. By dividing the entire world into this dualism of the Physical Being (Res Extensa) and the Thinking Being (Res Cogitans), eternally separated the world of thought from the world of three dimensional space. The effects of this separation can be felt in the preception of time as something homogenised and external to the body.

In a brief summary of his study into the I Ching, McKenna said, “Well, this sameness-but-different rule applies on all levels in a temporal hierarchy. Centuries are rather like each other, and yet occasionally a century will come along that is quite anomalous. We call this sameness-and-difference nesting fractal. This is a new branch of mathematics, and quite simply what the Chinese discovered circa 3,000 B.C. was the fractal nature of time, that the rules of expression of temporal elements which govern the rise and fall of dynasties also govern the rise and fall of love affairs and moods.”

Another, perhaps lesser known Greek concept of time was ‘Kairos’, which can be conceived of as a measure of qualitative time. Time, in this sense, is more of an aperture or a moment in which characterises this particular ‘Now’ as distinct from all others. Its etymological roots extend into archery, denoting the right moment to release an arrow from its bow, or into the artisanal sphere of weaving, where the thread must be passed through a momentary gap that appears in the fabric of the material.

Across the topology of this psyche, the effects of time being perceived as its own substance had taken a secondary position in favour of the energetic exploration and exploitation of space.

Time, in this instance was perceived as being ‘taken by the soul’ in order to necessitate change, and became a phenomena defined mostly in relation to the measurement of the objects within it.

Ethnobotanist and researcher of the Eastern philosophy of the Tao te Ching and the I Ching, Terence McKenna, once wrote that “the Chinese looked not at the world of matter, energy and space, but the world of time, and carried out a very rigorous analysis of their own perception and discovered to their amazement that time is actually composed of elements.”

It was the basis of McKenna’s Time Wave Zero theory and his later computer program that mapped ‘habits’ and ‘novelties’ that ebbed and flowed throughout an historical time-wave. In much the same way as the Western Periodic Table of chemical elements describes bonding relationships of physical matter, the I Ching was a table that described the elements within the ‘Physics of Time’, articulated through symbols known as Hexagrams.

‘Chronos’, the Greek word from which everyday ‘modern’ time is conceived, is a measure of quantitative time, sequential and chronological, and necessarily extends through the Cartesian model of the “res extensa” and “res cogitans” - the Radical Dualism that became the engine house for the subsequent worlds built upon the material sciences. By dividing the entire world into this dualism of the Physical Being (Res Extensa) and the Thinking Being (Res Cogitans), eternally separated the world of thought from the world of three dimensional space. The effects of this separation can be felt in the preception of time as something homogenised and external to the body.

In a brief summary of his study into the I Ching, McKenna said, “Well, this sameness-but-different rule applies on all levels in a temporal hierarchy. Centuries are rather like each other, and yet occasionally a century will come along that is quite anomalous. We call this sameness-and-difference nesting fractal. This is a new branch of mathematics, and quite simply what the Chinese discovered circa 3,000 B.C. was the fractal nature of time, that the rules of expression of temporal elements which govern the rise and fall of dynasties also govern the rise and fall of love affairs and moods.”

Another, perhaps lesser known Greek concept of time was ‘Kairos’, which can be conceived of as a measure of qualitative time. Time, in this sense, is more of an aperture or a moment in which characterises this particular ‘Now’ as distinct from all others. Its etymological roots extend into archery, denoting the right moment to release an arrow from its bow, or into the artisanal sphere of weaving, where the thread must be passed through a momentary gap that appears in the fabric of the material.

“Real duration is that duration which gnaws on things, and leaves on them the mark of its tooth. If everything is in time, everything changes inwardly, and the same concrete reality never recurs. Repetition is therefore possible only in the abstract: what is repeated is some aspect that our senses, and especially our intellect, have singled out from reality, just because our action, upon which all the effort of our intellect is directed, can move only among repetitions. Thus, concentrated on that which repeats, solely preoccupied in welding the same to the same, intellect turns away from the vision of time. It dislikes what is fluid, and solidifies everything it touches. We do not think real time. But we live it, because life transcends intellect. - Henri Bergson.

Much like the I Ching being rendered as a sequence of relational, wave-like effects, Kairos also shares a similar atmospheric quality that directs time more towards a series of nested fractals within a larger body that becomes a sensorial experience rather than one purely of measurement.

The prominent French vitalist and anti-rationalist philosopher, Gilles Deleuze, in his book ’Cinema 2: The Time-Image’, uses the philosophy of Henri Bergson to analyse the cinematic treatment of time and memory, thought and speech.

Deleuze presents the idea that in Europe during the post-war period, the relationship to space, especially abandoned and desolate urban space, altered the ability to act, and a new race of characters stirred in the transition like a strange kind of mutant, who ‘looked’ rather than ‘acted’.

It was this change in sense-ratios of the sensory-motor schema that prompted the dislocation from the Action-Image of the old Cinema and towards a loosening, which let the Time-Image seep through. Deleuze states that “the image itself is the system of the relationships between its elements, that is, a set of relationships of time from which the variable present only flows…“

The prominent French vitalist and anti-rationalist philosopher, Gilles Deleuze, in his book ’Cinema 2: The Time-Image’, uses the philosophy of Henri Bergson to analyse the cinematic treatment of time and memory, thought and speech.

Deleuze presents the idea that in Europe during the post-war period, the relationship to space, especially abandoned and desolate urban space, altered the ability to act, and a new race of characters stirred in the transition like a strange kind of mutant, who ‘looked’ rather than ‘acted’.

It was this change in sense-ratios of the sensory-motor schema that prompted the dislocation from the Action-Image of the old Cinema and towards a loosening, which let the Time-Image seep through. Deleuze states that “the image itself is the system of the relationships between its elements, that is, a set of relationships of time from which the variable present only flows…“

In ‘Matter and Memory’, Bergson writes, “The past has not ceased to exist; it has only ceased to be useful. But how can the past, which has ceased to be, preserve itself? Have we not here a real contradiction?… You define the present in an arbitrary manner as that ‘which is’, whereas the present is simply ‘what is being made’. Nothing is less than the present moment, if you understand by that the indivisible limit which divides the past from the future.

When we think this present as going to be, it exists not yet; and when we think it as existing, it is already past. If, on the other hand, what you are considering is the concrete present such as it is actually lived by consciousness, we may say that this present consists, in large measure, in the immediate past. In the fraction of a second which covers the briefest possible perception of light, billions of vibrations have taken place, of which the first is separated from the last by an interval which is enormously divided. Your perception, however instantaneous, consists then in an incalculable multitude of remembered elements; and in truth every perception is already memory.”

This distinction between pure memory (virtual) and pure perception (actual) is constantly being bridged by accessing degrees of time in a display that perpetually surges from the past towards and immediate future. It indicates that time is not a substance to pass over but to plunge into, as in the aether (or ‘dressed space’ of Aristotle), it is constantly being renewed. Seen from this new point of view, our body is also part of our image representation, which is ever being born again. For Bergson, “this is why it is a chimerical enterprise to seek to localise past or even present perceptions in the brain : they are not in it; it is the brain that is in them”, as lived through consciousness, in which our habitual actions try to deny.

It is necessary that time should descend from the heights of pure memory down to the precise point where action is taking place. The highest tension of the soul in the deepest sense of time. For Deleuze, this coalescence of energies culminated in what he termed the Crystal-Image of time.

When we think this present as going to be, it exists not yet; and when we think it as existing, it is already past. If, on the other hand, what you are considering is the concrete present such as it is actually lived by consciousness, we may say that this present consists, in large measure, in the immediate past. In the fraction of a second which covers the briefest possible perception of light, billions of vibrations have taken place, of which the first is separated from the last by an interval which is enormously divided. Your perception, however instantaneous, consists then in an incalculable multitude of remembered elements; and in truth every perception is already memory.”

This distinction between pure memory (virtual) and pure perception (actual) is constantly being bridged by accessing degrees of time in a display that perpetually surges from the past towards and immediate future. It indicates that time is not a substance to pass over but to plunge into, as in the aether (or ‘dressed space’ of Aristotle), it is constantly being renewed. Seen from this new point of view, our body is also part of our image representation, which is ever being born again. For Bergson, “this is why it is a chimerical enterprise to seek to localise past or even present perceptions in the brain : they are not in it; it is the brain that is in them”, as lived through consciousness, in which our habitual actions try to deny.

It is necessary that time should descend from the heights of pure memory down to the precise point where action is taking place. The highest tension of the soul in the deepest sense of time. For Deleuze, this coalescence of energies culminated in what he termed the Crystal-Image of time.

“ If these be vague words, then seek not to clear them. Vague and nebulous is the beginning of all things, but not their end, and I fain would have you remember me as a beginning.

Life, and all that lives, is conceived in the mist and not in the crystal. And who knows but a crystal is mist in decay?” - Khalil Gibran.

For Deluze, the Crystal-Image of time showed how these attributes of habit and memory were expressed through the cinematic image, for in the cinema, the image had to be surrounded by a world, an extended body that provided vast networks of curcuits between virtual and actual memory. This new form of cinematic image, for Deleuze, was how we experienced time as the co-existence of past and present - the Kairos of deep time.

What constitutes the purest crystal image is when the “actual optical image crystallises with its own virtual image” - as a kaleidoscope (or coll-idea-oscope) divides and relates among all the senses which are altered through collisions taking place in the total environment.

“Time has to split at the same time as it sets itself out or unrolls itself: it splits in two dissymmetrical jets, one of which makes all the present pass on, while the other preserves all the past. Time consists of this split, and it is this, it is time, that we see in the crystal. The crystal-image was not time, but we see time in the crystal. We see in the crystal the perpetual foundation of time, non-chronological time… This is the powerful, non-organic Life which grips the world. The visionary, the seer, is the one who sees in the crystal, and what he sees is the gushing of time as dividing in two, as splitting.“

The crystal-image metaphor is used as a container of a mirrored nature - a reciprocity of real and imagined, of mythical and historical memory, with the physical being condensed through the decay of mist into its crystal-image, to use Gibran’s poetic phrase.

This mutual and dual nature is not produced in the mind, but is an objective characteristic of certain existing images which are by their very nature double. The most familiar case being the mirror.

The fragmentation of this mirror-image is what Deleuze called the ‘hyalosign’ (or glass-sign) as the indiscernible nature of the mirror can either become transparent or opaque. “Since the indiscernible exchange is always renewed and reproduced… the transcendental form of time is what we see in the crystal; and hyalosigns, and crystalline signs, should therefore be called mirrors or seeds of time.”

What constitutes the purest crystal image is when the “actual optical image crystallises with its own virtual image” - as a kaleidoscope (or coll-idea-oscope) divides and relates among all the senses which are altered through collisions taking place in the total environment.

“Time has to split at the same time as it sets itself out or unrolls itself: it splits in two dissymmetrical jets, one of which makes all the present pass on, while the other preserves all the past. Time consists of this split, and it is this, it is time, that we see in the crystal. The crystal-image was not time, but we see time in the crystal. We see in the crystal the perpetual foundation of time, non-chronological time… This is the powerful, non-organic Life which grips the world. The visionary, the seer, is the one who sees in the crystal, and what he sees is the gushing of time as dividing in two, as splitting.“

The crystal-image metaphor is used as a container of a mirrored nature - a reciprocity of real and imagined, of mythical and historical memory, with the physical being condensed through the decay of mist into its crystal-image, to use Gibran’s poetic phrase.

This mutual and dual nature is not produced in the mind, but is an objective characteristic of certain existing images which are by their very nature double. The most familiar case being the mirror.

The fragmentation of this mirror-image is what Deleuze called the ‘hyalosign’ (or glass-sign) as the indiscernible nature of the mirror can either become transparent or opaque. “Since the indiscernible exchange is always renewed and reproduced… the transcendental form of time is what we see in the crystal; and hyalosigns, and crystalline signs, should therefore be called mirrors or seeds of time.”

In the narrative of Kamler’s Chronopolis, the Chronos of repetitive and quantitative time is the psychic environment that defines the existence of the Seers. Having reached immortality, they occupy a physical space that rests upon the farthest regions of Chronos - or perhaps of Aion - the orb of timelessness, and as such their bodies are bound to their intellect.

Later in the film their existence is disrupted by the fall of a curious traveller who lands upon their world. After encountering their sentient technology, his own relative experience of time, and by extension, that of the Seers, is altered through the spontaneity of the Kairos - the intuitive dimension of time.

After reaching into the heart of an opaque orb, the crystal-image of time becomes both the hyalosign and the mirror-sign, as the pyschic shift in the experience of time occurs in the world of Chronopolis, and thus ushers in the potentiality of its own reconstruction.

“If, here again, we imagine a number of possible repetitions of the totality of our memories” writes Bergson, then “each of these copies of our past life must be cut into definite parts, and the cutting up is not the same when we pass from one copy to another, each of them being in fact characterised by the particular kind of dominant memories on which the other memories lean upon.”

Therefore, each copy is new, and “these systems are not formed of recollections laid side by side like so many atoms. There are always some dominant memories, shining points round which the others form a vague nebulosity. These shining points are multiplied in the degree in which our memory expands… The work of localisation consists, in reality, in a growing effort of expansion, by which the memory, always present in its entirety to itself, spreads out its recollections over an ever wider surface and so ends by distinguishing, in what was till then a confused mass, the remembrance which could not find its proper place.”

Later in the film their existence is disrupted by the fall of a curious traveller who lands upon their world. After encountering their sentient technology, his own relative experience of time, and by extension, that of the Seers, is altered through the spontaneity of the Kairos - the intuitive dimension of time.

After reaching into the heart of an opaque orb, the crystal-image of time becomes both the hyalosign and the mirror-sign, as the pyschic shift in the experience of time occurs in the world of Chronopolis, and thus ushers in the potentiality of its own reconstruction.

“If, here again, we imagine a number of possible repetitions of the totality of our memories” writes Bergson, then “each of these copies of our past life must be cut into definite parts, and the cutting up is not the same when we pass from one copy to another, each of them being in fact characterised by the particular kind of dominant memories on which the other memories lean upon.”

Therefore, each copy is new, and “these systems are not formed of recollections laid side by side like so many atoms. There are always some dominant memories, shining points round which the others form a vague nebulosity. These shining points are multiplied in the degree in which our memory expands… The work of localisation consists, in reality, in a growing effort of expansion, by which the memory, always present in its entirety to itself, spreads out its recollections over an ever wider surface and so ends by distinguishing, in what was till then a confused mass, the remembrance which could not find its proper place.”

Further Reading ︎

Reincarnation in Robots - Thinking Allowed.

Non-local Minds and Reincarnation Machines.

Rise of the Machines, Martin Ford.

Deleuze and the Crystal Image, article.

Cinema 2: The Time-Image, Gilles Deleuze, pdf.

Memory and Matter, Henri Bergson, website.

Creative Evolution, Henri Bergson, website.

Aristotle on The Perception and Cognition of Time, John Bowin, pdf.

la venta

︎Culture, Video, Sculpture, Spirituality.

︎ Ventral Is Golden

la venta

︎Culture, Video, Sculpture, Spirituality.

︎ Ventral Is Golden

︎ Ventral Is Golden

"When the human race learns to read the language of symbolism, a great veil will fall from the eyes of men"

- Manly P. Hall

- Manly P. Hall

According to oral tradition, the area of ‘La Venta’ gets its modern name from the fact that precious woods were once sold there. It is considered one of the first cities of ancient Mexico (1200-400 BC), settled in a region of prodigal nature. The footprint of the mysterious Olmecs can be found in the urban layout, where the amazing stone sculptures - some weighing 35 tons - and jade offerings have been found.

The ‘mysterious’ nature of the Olmecs is attested to their sudden appearence in the meso-american region near the gulf of Mexico. Although their influence can be felt as far as Belize and across the coast of the Yucatan, their origins are still a focus of much debate amongst scholars today.

Most of their symbolic and ritual artefacts are considered to be the source of other prominent cultures from the Mayans, Zapotecs and Aztec, such as pyramid building, the astronomical alginment of structures, writing, the ball game (pok-a-pok), the veneration of the jaguar deity, and the first representation of the feathered serpent, to name only a few.

Unlike later Maya or Aztec cities, La Venta was built from earth and clay. Large basalt stones were brought from the Tuxtla Mountains and were used almost exclusively for monuments such as the altars / thrones and the more culturally renouned ‘colossal heads’ of the Olmec priests, shamans and warrior classes (four of which were found at La Venta).

It is thought that little more than half of the ancient city survived modern disturbances enough to map accurately. Today, the entire southern end of the site is covered by a petroleum refinery and has been largely demolished, making excavations difficult or impossible. As a result, many of the site's monuments are now on display in the archaeological museum and park in the city of Villahermosa, Tabasco.

It is said that La Venta “housed a complex and surely hierarchical society, which sustained itself from the intense cultivation of maize and cassava (which the Olmecs domesticated both relatively early to obtain up to three annual harvests). They also knew how to take advantage of the richness of the very humid alluvial soils and the abundant water deposits and currents, with the Tonalá River and its tributaries surrounding the main site of La Venta (which was originally a small island) as well as an ecosystem rich in edible plants and animals.” (source).

Below is a beautiful documentary (originally presented by the University California, Berkeley) of an excavation taking place at La Venta during a 1963 expedition. It is an insightful introduction and overview of the Olmec culture and what was one of their principle cultural and religious sites.

The ‘mysterious’ nature of the Olmecs is attested to their sudden appearence in the meso-american region near the gulf of Mexico. Although their influence can be felt as far as Belize and across the coast of the Yucatan, their origins are still a focus of much debate amongst scholars today.

Most of their symbolic and ritual artefacts are considered to be the source of other prominent cultures from the Mayans, Zapotecs and Aztec, such as pyramid building, the astronomical alginment of structures, writing, the ball game (pok-a-pok), the veneration of the jaguar deity, and the first representation of the feathered serpent, to name only a few.

Unlike later Maya or Aztec cities, La Venta was built from earth and clay. Large basalt stones were brought from the Tuxtla Mountains and were used almost exclusively for monuments such as the altars / thrones and the more culturally renouned ‘colossal heads’ of the Olmec priests, shamans and warrior classes (four of which were found at La Venta).

It is thought that little more than half of the ancient city survived modern disturbances enough to map accurately. Today, the entire southern end of the site is covered by a petroleum refinery and has been largely demolished, making excavations difficult or impossible. As a result, many of the site's monuments are now on display in the archaeological museum and park in the city of Villahermosa, Tabasco.

It is said that La Venta “housed a complex and surely hierarchical society, which sustained itself from the intense cultivation of maize and cassava (which the Olmecs domesticated both relatively early to obtain up to three annual harvests). They also knew how to take advantage of the richness of the very humid alluvial soils and the abundant water deposits and currents, with the Tonalá River and its tributaries surrounding the main site of La Venta (which was originally a small island) as well as an ecosystem rich in edible plants and animals.” (source).

Below is a beautiful documentary (originally presented by the University California, Berkeley) of an excavation taking place at La Venta during a 1963 expedition. It is an insightful introduction and overview of the Olmec culture and what was one of their principle cultural and religious sites.

︎ Altar 4 in its orignal position at La Venta.

︎ Discovery of an Olmec Collosal Head.

︎ Offering 4 (900BC), consiting of jade, granite and serpentine figures in a circular position, La Venta.

︎ Altar 5, La Venta. Photo by Ventral is Golden (2021).

︎ Olmec Tomb, La Venta. Photo by Ventral is Golden (2021).

︎ The Governor, La Venta. Photo by Ventral is Golden (2021).

︎ Collosal Head, La Venta. Photo by Ventral is Golden (2021).

evangelions

︎Culture, Spirituality, Article

︎ Ventral Is Golden

evangelions

︎Culture, Spirituality, Article

︎ Ventral Is Golden

︎ Ventral Is Golden

"All the gods, all the heavens, all the world, are within us. They are magnified dreams, and dreams are manifestations in image form of the energies of the body." - Joseph Campbell.

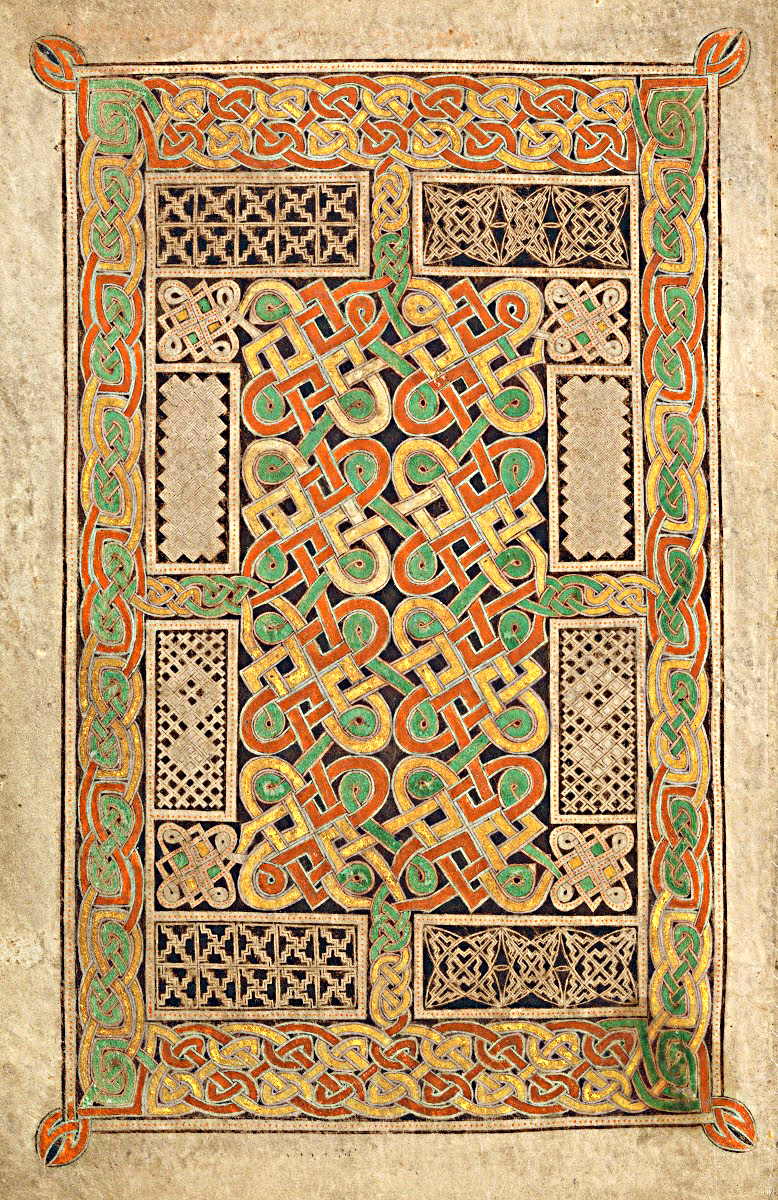

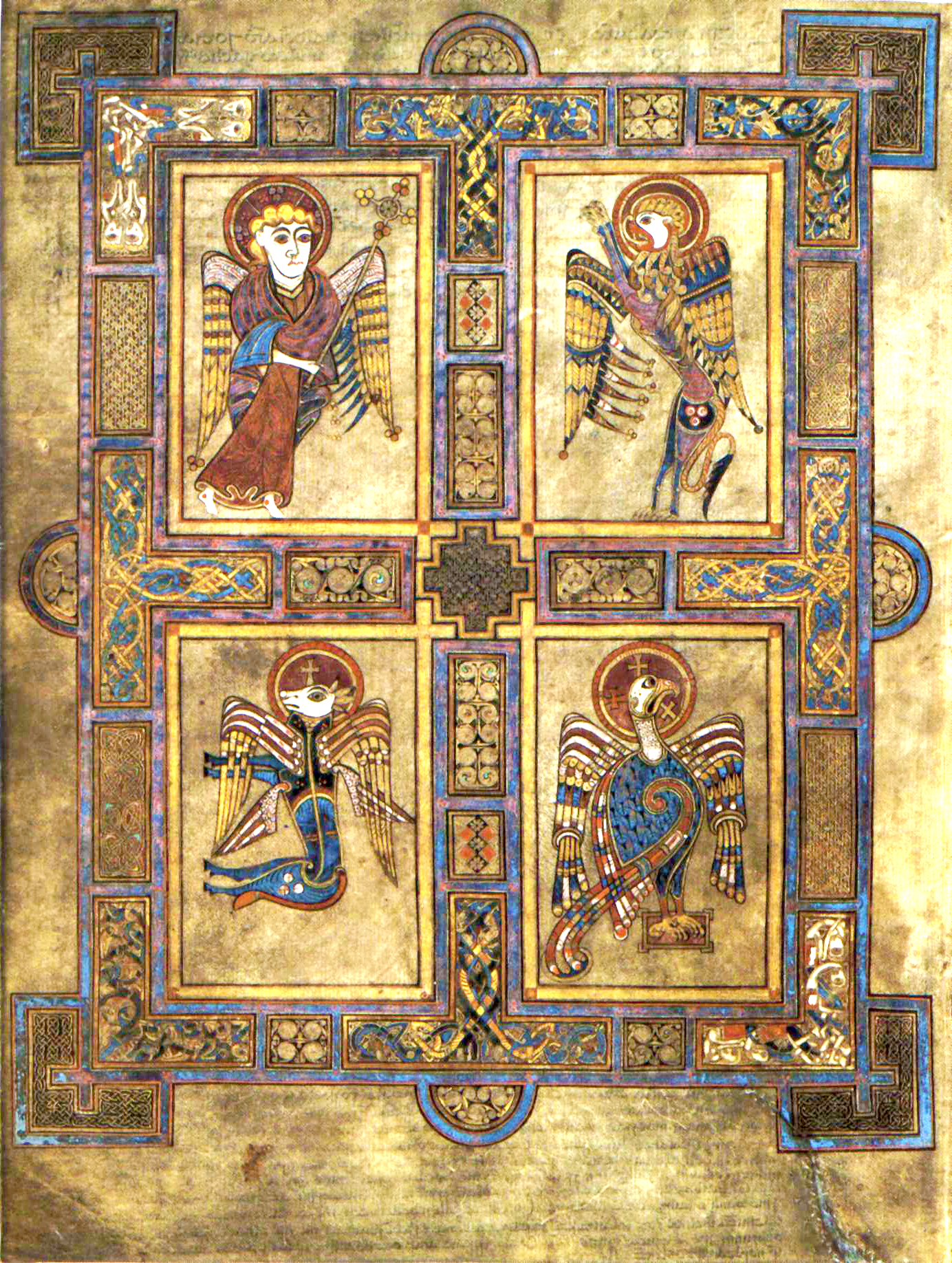

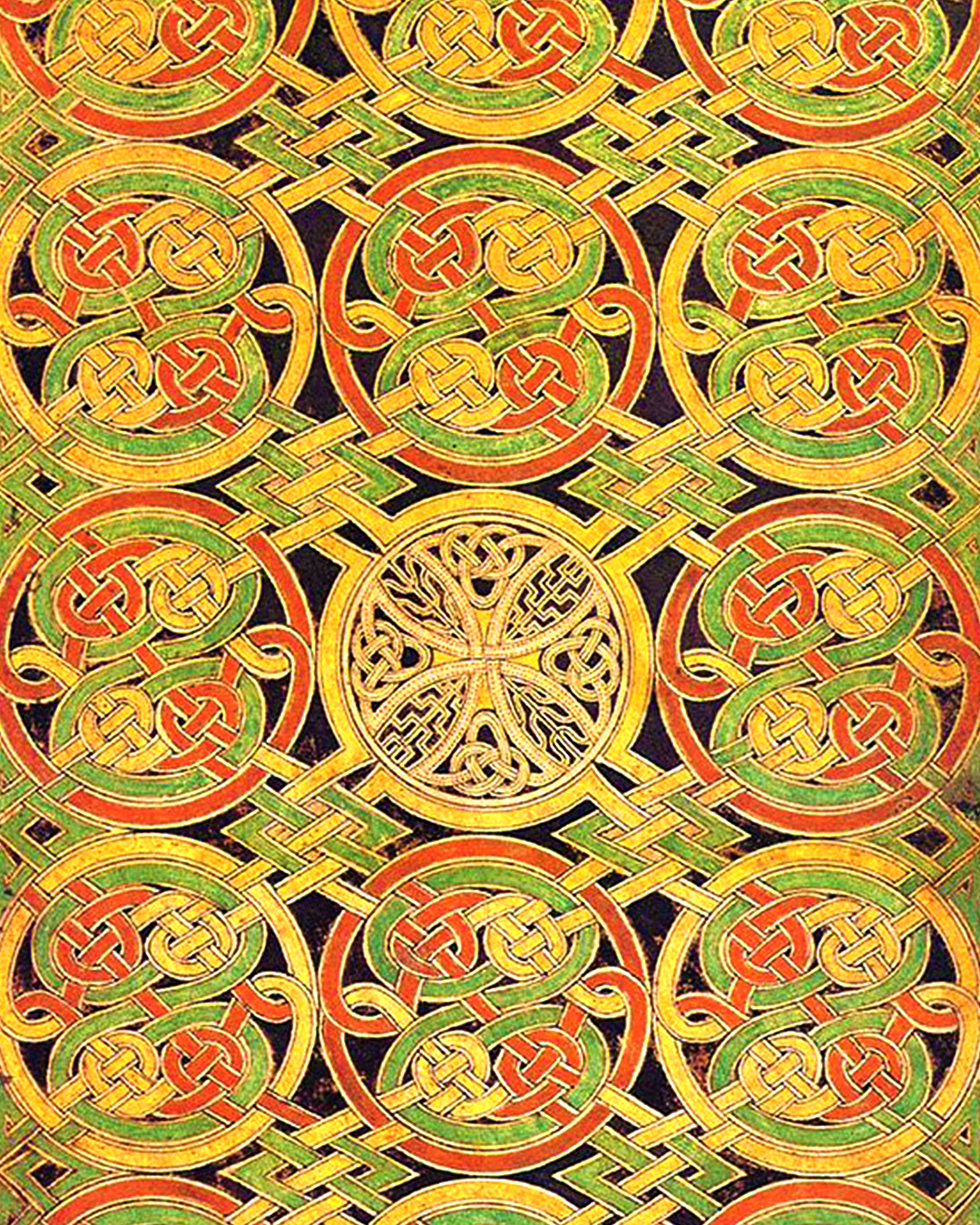

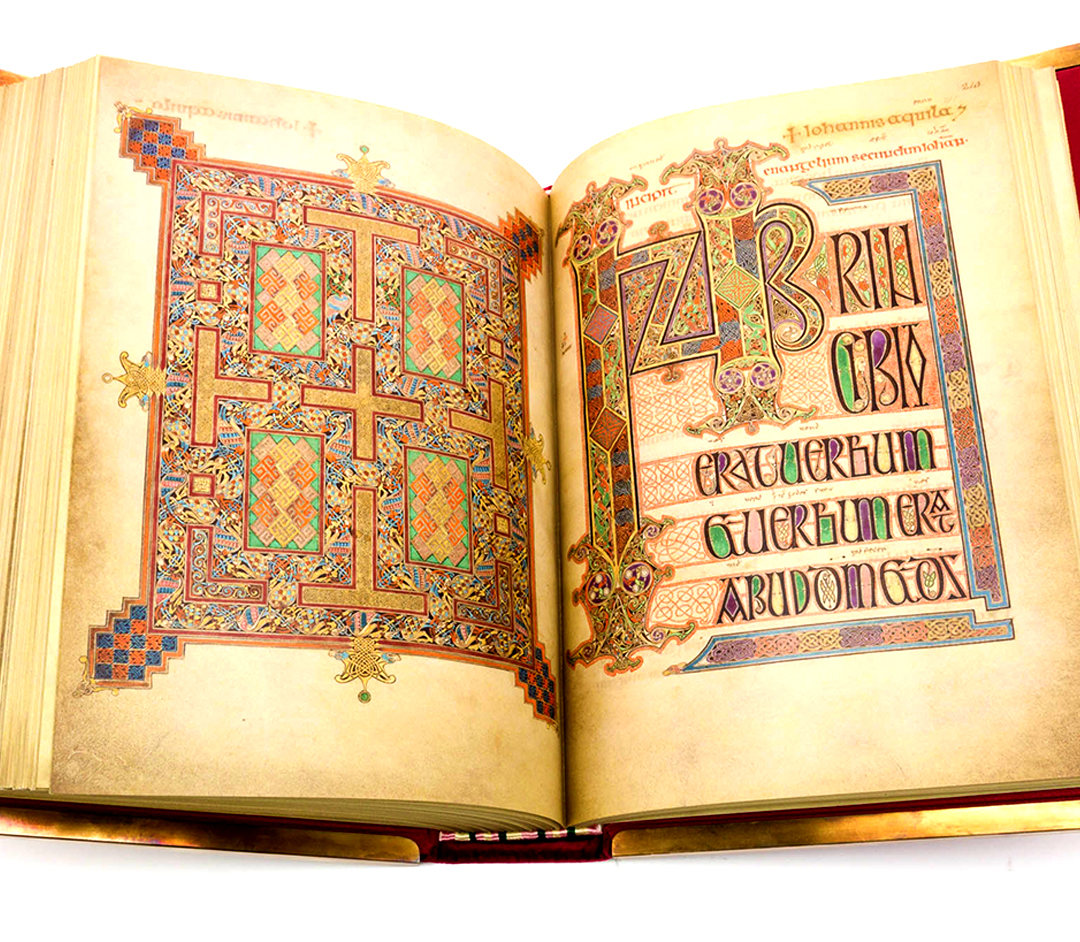

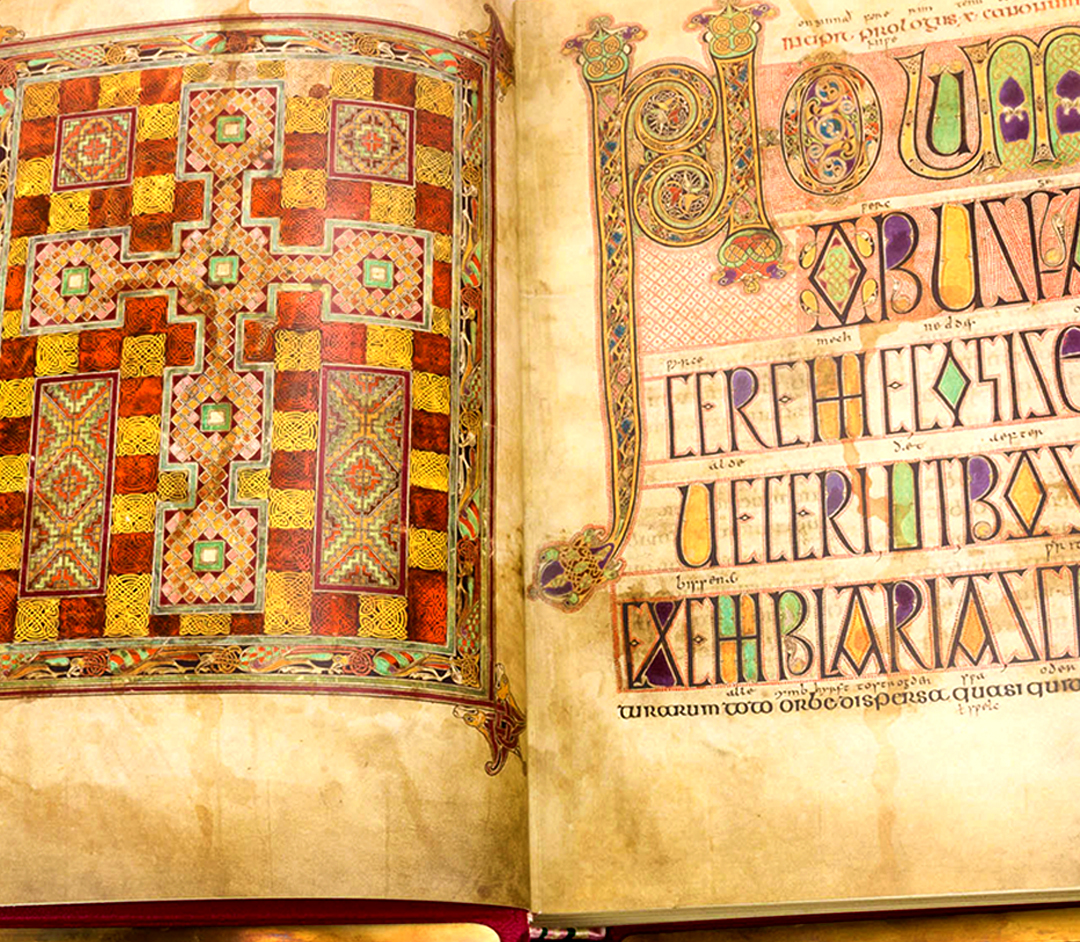

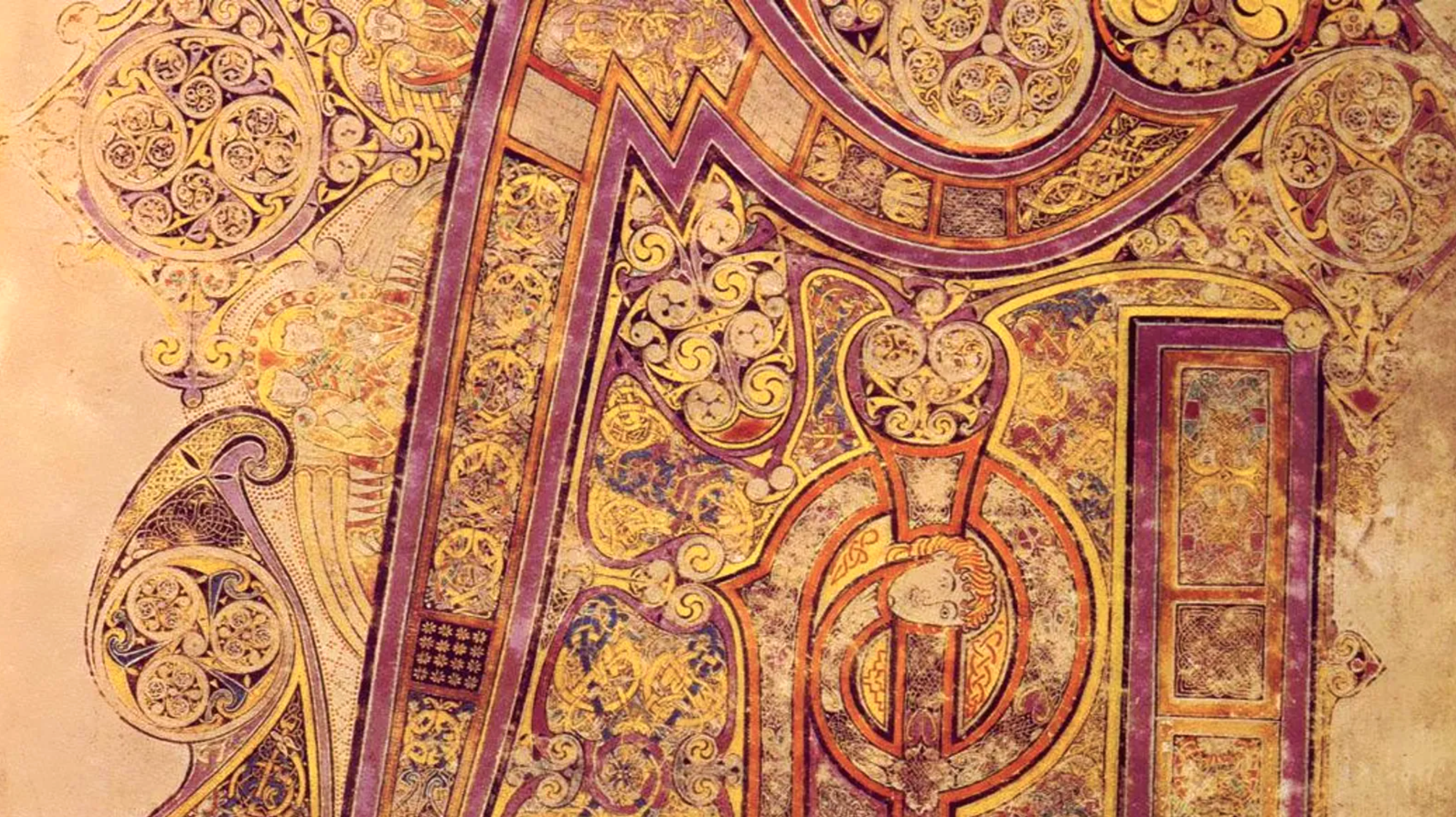

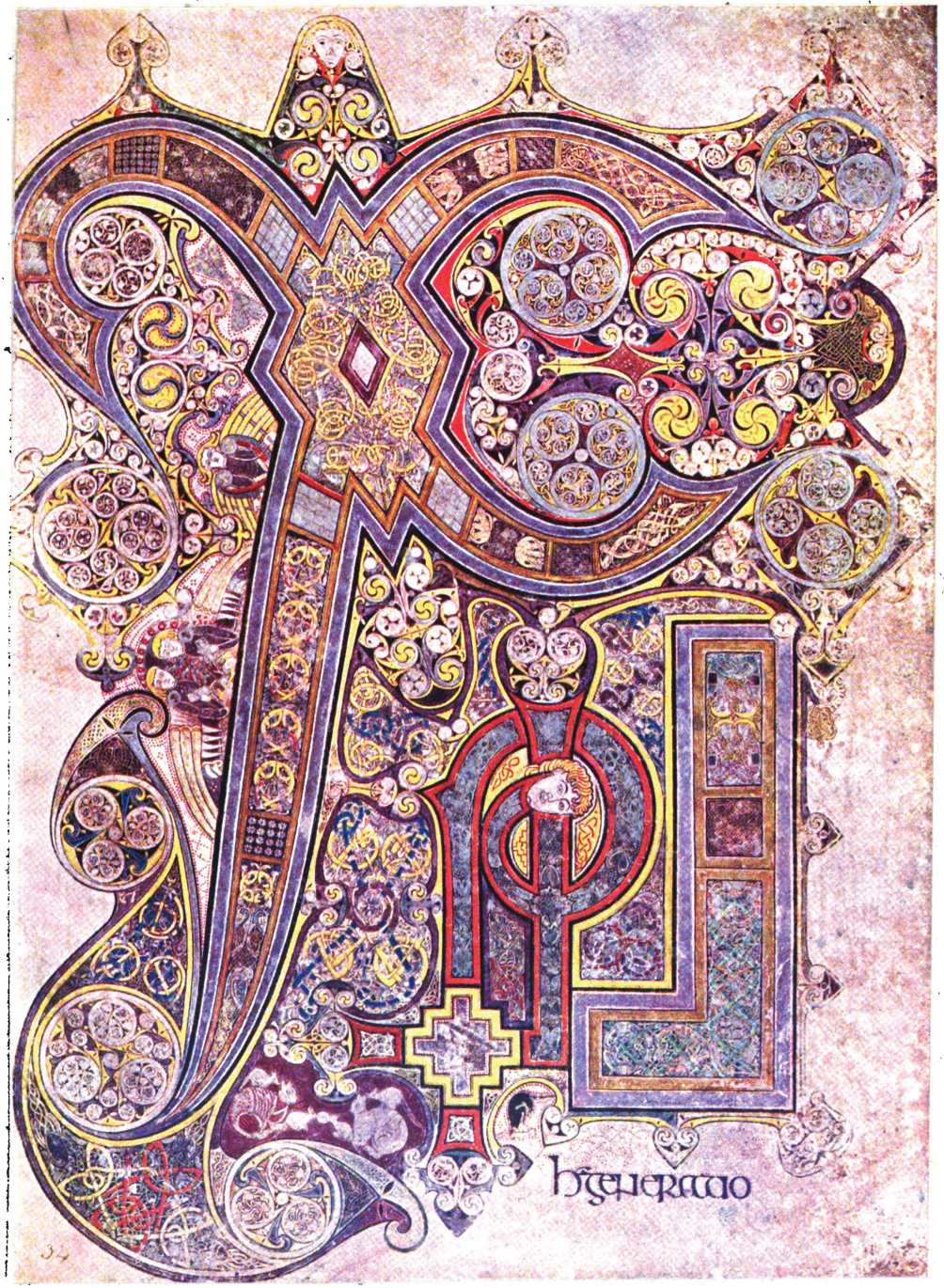

The trilogy of Evengelions (or Gospel Books) known individually from the British Isles as the Book of Durrow, the Lindisfarne Gospels and the Book of Kells, are some of the most intricate examples of art from medieval Europe and are renowned for their cultural significance, production techniques, treasure binding, typographic composition and ‘carpet pages’.

Dating from around 650AD - 800AD, their symbology reveals the art of early pre-christian Celtic and Germanic peoples which formed the earliest examples of a clear fusion between disparate decorative motifs and designs, aspects of which would later become the Insular style, featuring zoomorphic interlace from the Migration period in western Europe, where pre-existent spiral motifs of Celtic decoration from the Bronze Age, animal and human forms from Pictish stone carving and the woven interlace and keys of Mediterranean origin (source) began to resurface and fuse together as the western part of the Roman Empire almost collapsed.

Although distinctly Christian in context by way of their content, which narrates the four Evangelists (or bringers of good news), their symbolic conceptualisation is undoubtedly pre-christian and astrological in nature.

As ancient historian, Bede explained, in a Christian context, each of the four Evangelists were represented by their own symbol: Matthew was the man, representing the human Christ; Mark was the lion, symbolising the triumphant Christ of the Resurrection; Luke was the calf, symbolising the sacrificial victim of the Crucifixion; and John was the eagle, symbolising Christ's second coming. Collectively they are known as the Tetramorphs, and their symbolism is centred primarily in the knowledge of astrology, with their most popular visual form surviving into modern times as the ‘World’ card of the Tarot‘s Major Arcana.

Although most Insular art originates from the Irish monastic movement of Celtic Christianity, or La Tène metalwork for the secular elite in the period beginning around 600AD, with the combining of Celtic and Anglo-Saxon styles, many of the patterns used for the Lindisfarne Gospels for example, date back to the pre-christian era, possibly even as far back as Egyptian Coptic Christianity (100AD) and the Druidic tradition (100BC) of the British Isles.

The gospels can be interpreted as an accumulation of cultural symbology that were articulated in a time of great political and religious change within the Euopean Dark Ages.

Historically tracable to the region of Wales in around 200BC, the Druidic order was the primary spiritual practice of the Celtic and Gaulish cultures.

As they had no written records, most of what is gleaned about them by modern historians comes through Roman sources, who may have exaggerated elements of their ritual practices of human sacrifice but definitively praised them for their abilities in mathematics and feats of memory, so much so that their power and respect was recognised as a threat to the Roman empire, and their practices outlawed.

The trinity of Evengelions all feature prominent pre-christian, druidic symbology, such as the Triquerta, Wheel of Taranis, Triskelion and Dara Knot. Druidic symbology (and of other animist traditions) often venerated the architecture of the spiral and the cross to relate instrinsically to the conception of God as the uncreated form of universal energy. The processes of measuring this force arguably gave rise to a number of techniques for organising space, such as time-keeping, making astrological alignments and consturcting monolithic monuments based on the spiralling nature of the moon’s journey through the sky. The conception of God, personified in this very same movement, underlies almost all of the visual vocabulary that anicent cultures used to define the forces which remained hidden behind the physcial world, and is expressed in the druidic proverb “Nid dim ond duw, Nid duw ond dim.“ which has the following translations:

There is nothing Uncreated but that which is hidden.

There is nothing not so concievable but that which is immeasurable.

There is no God but that which is Uncreated.

Only the Uncreated is hidden.

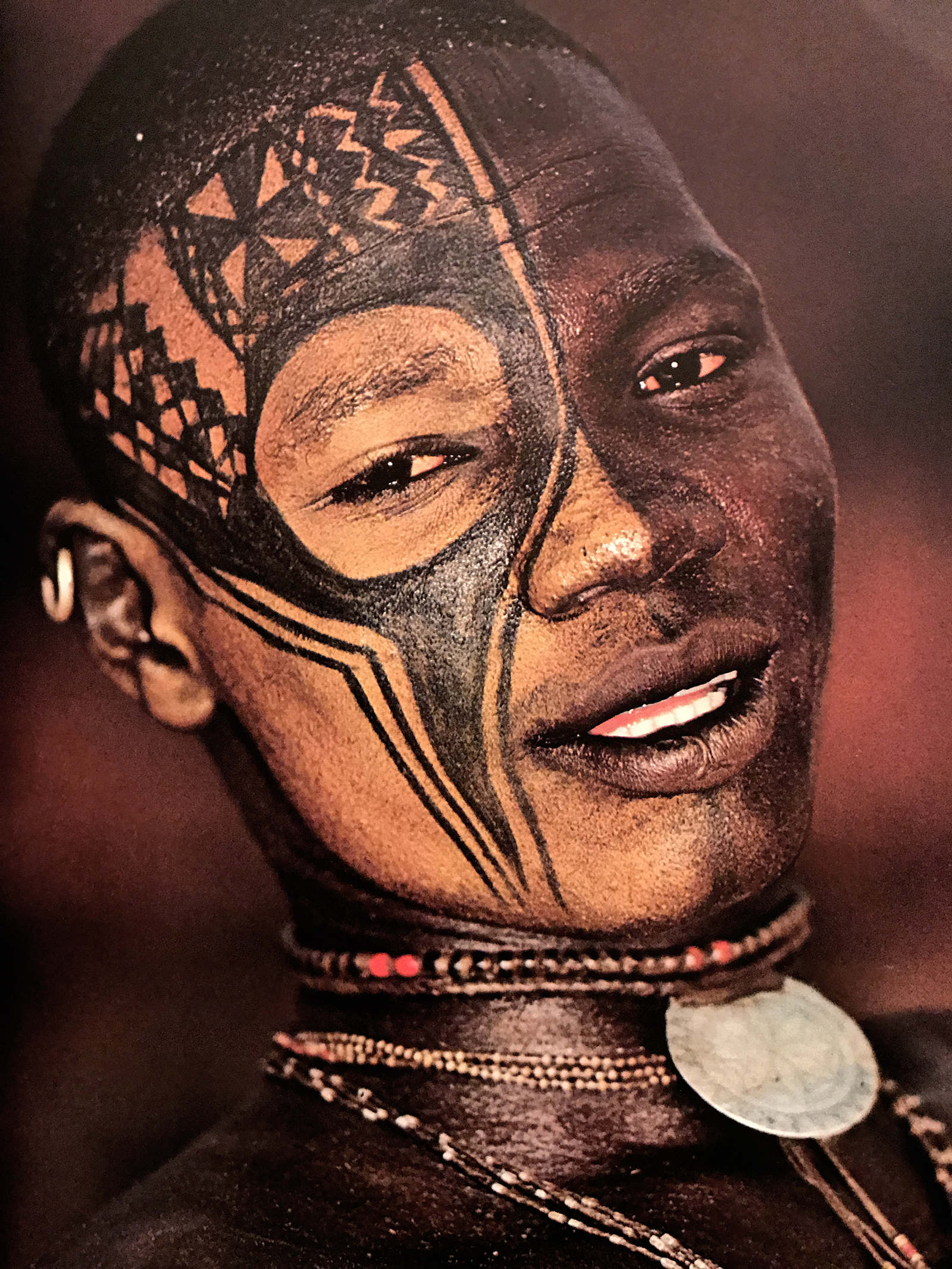

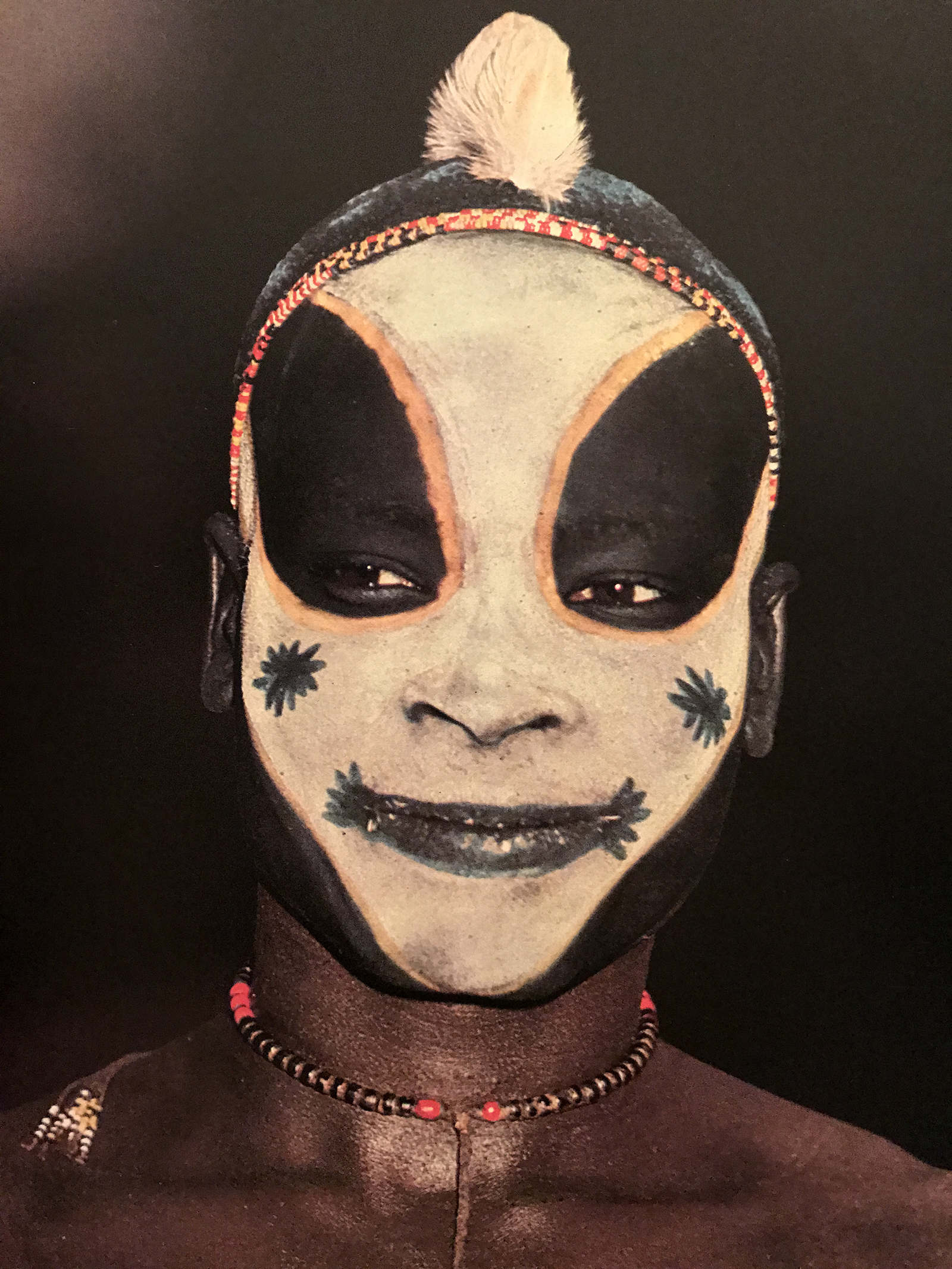

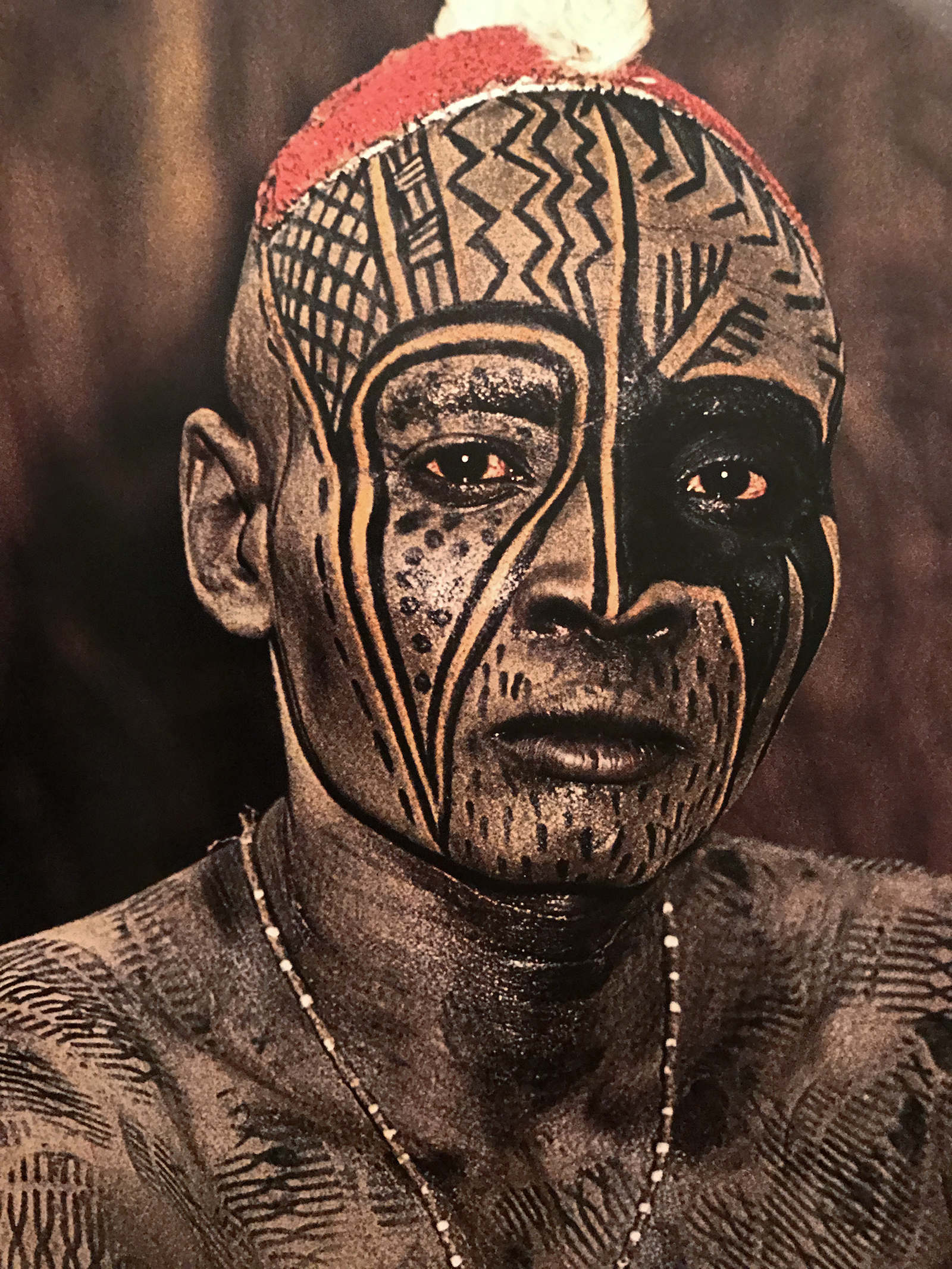

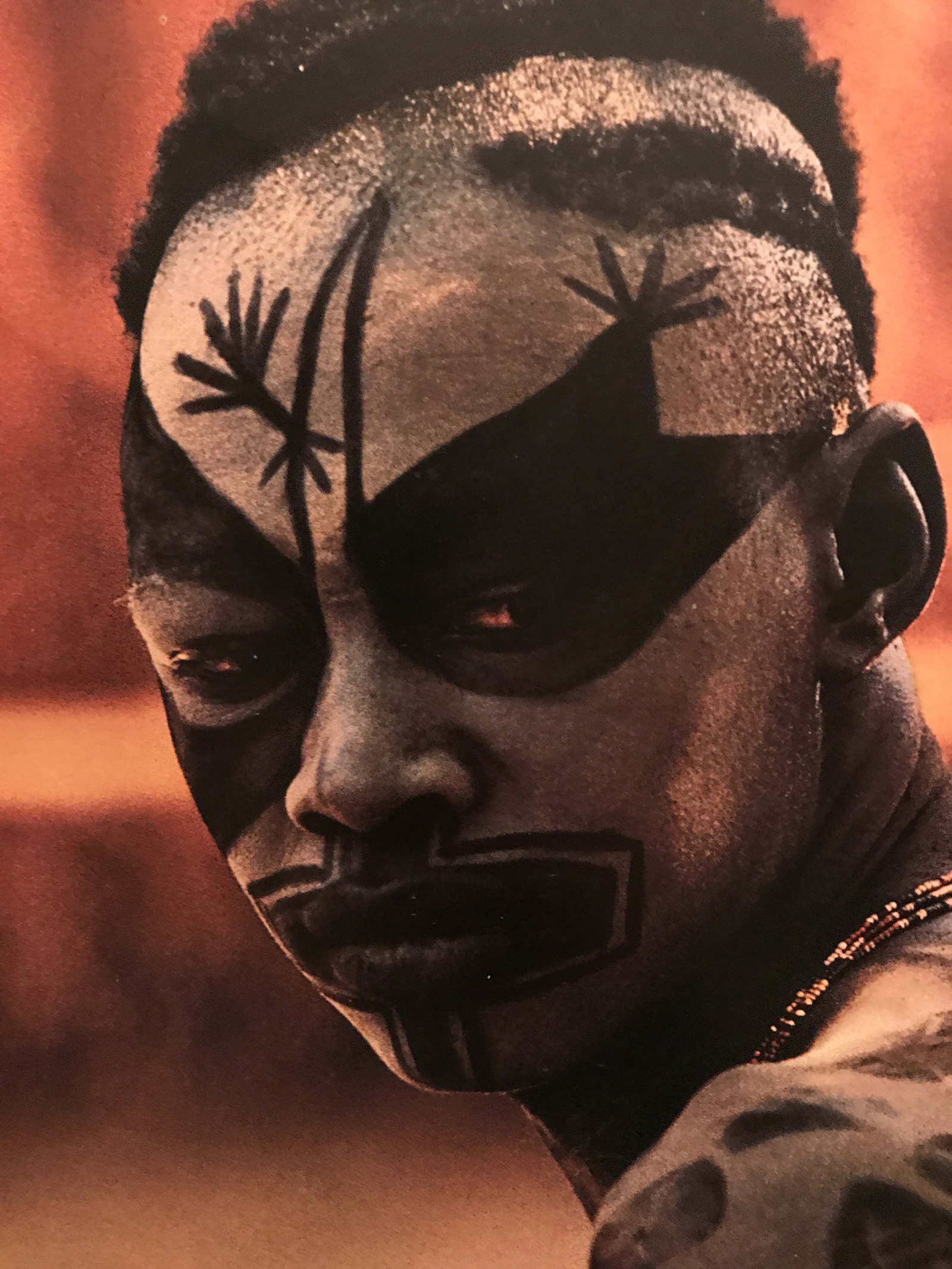

Nothing without God, without God no thing.

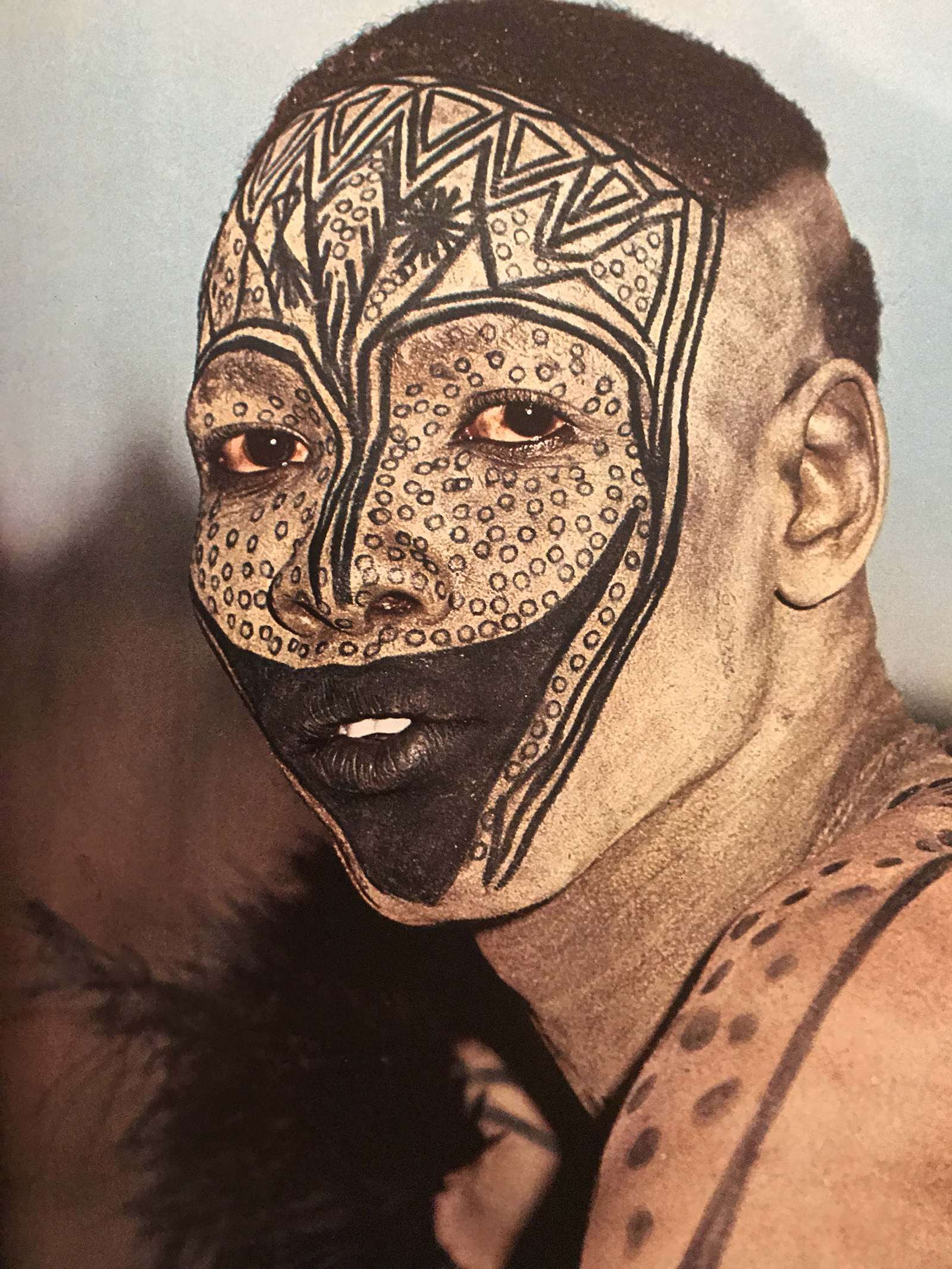

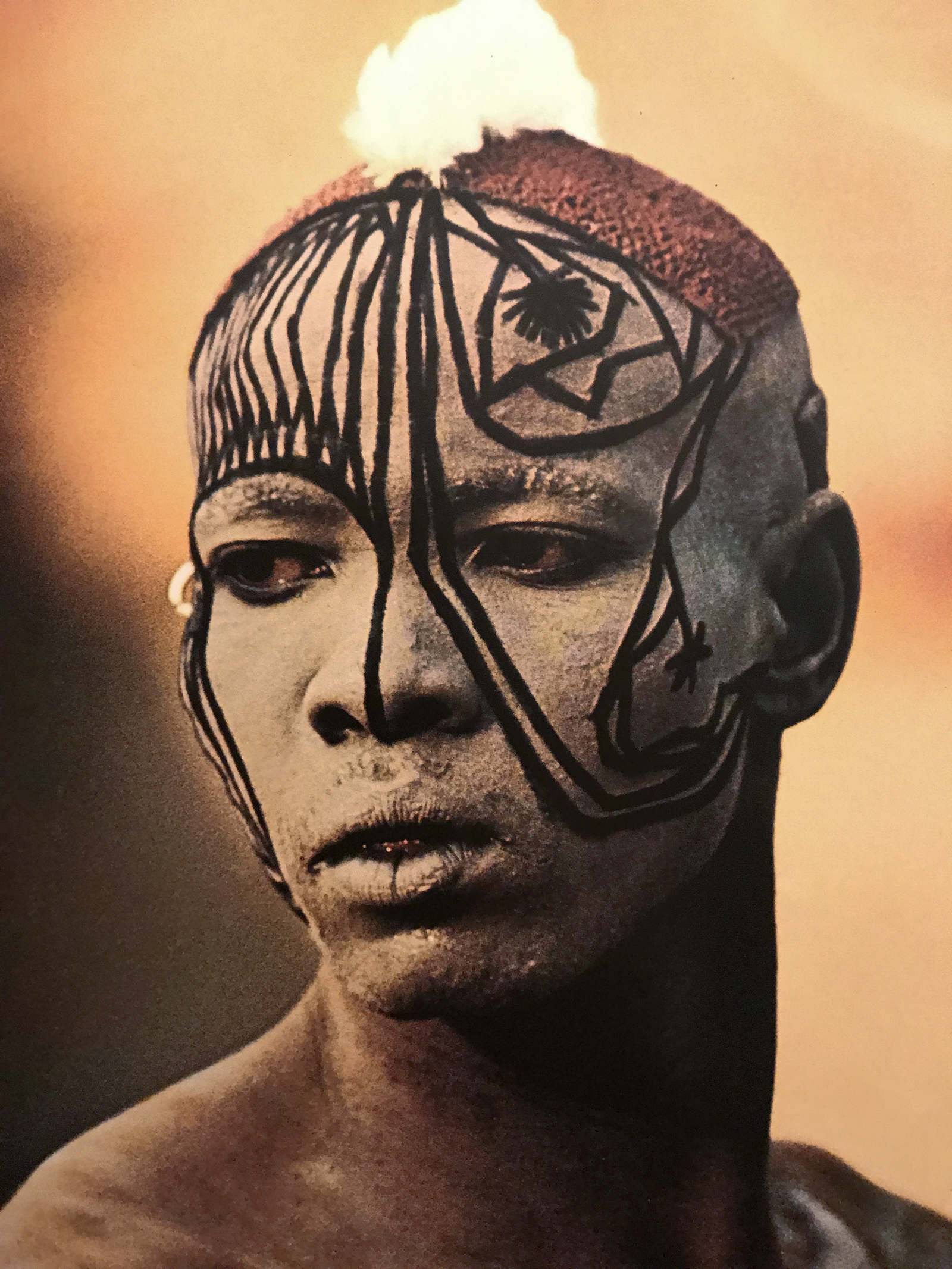

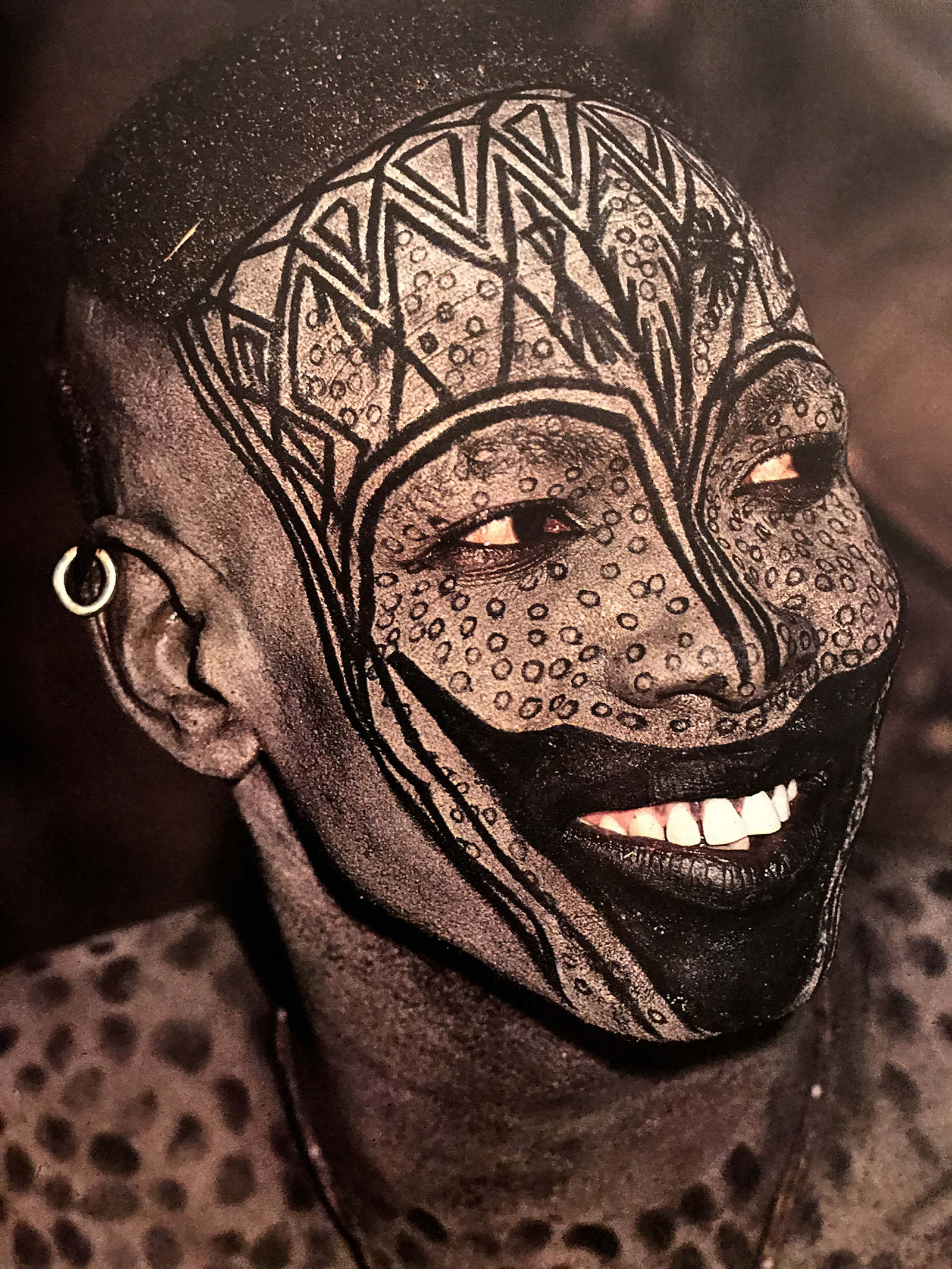

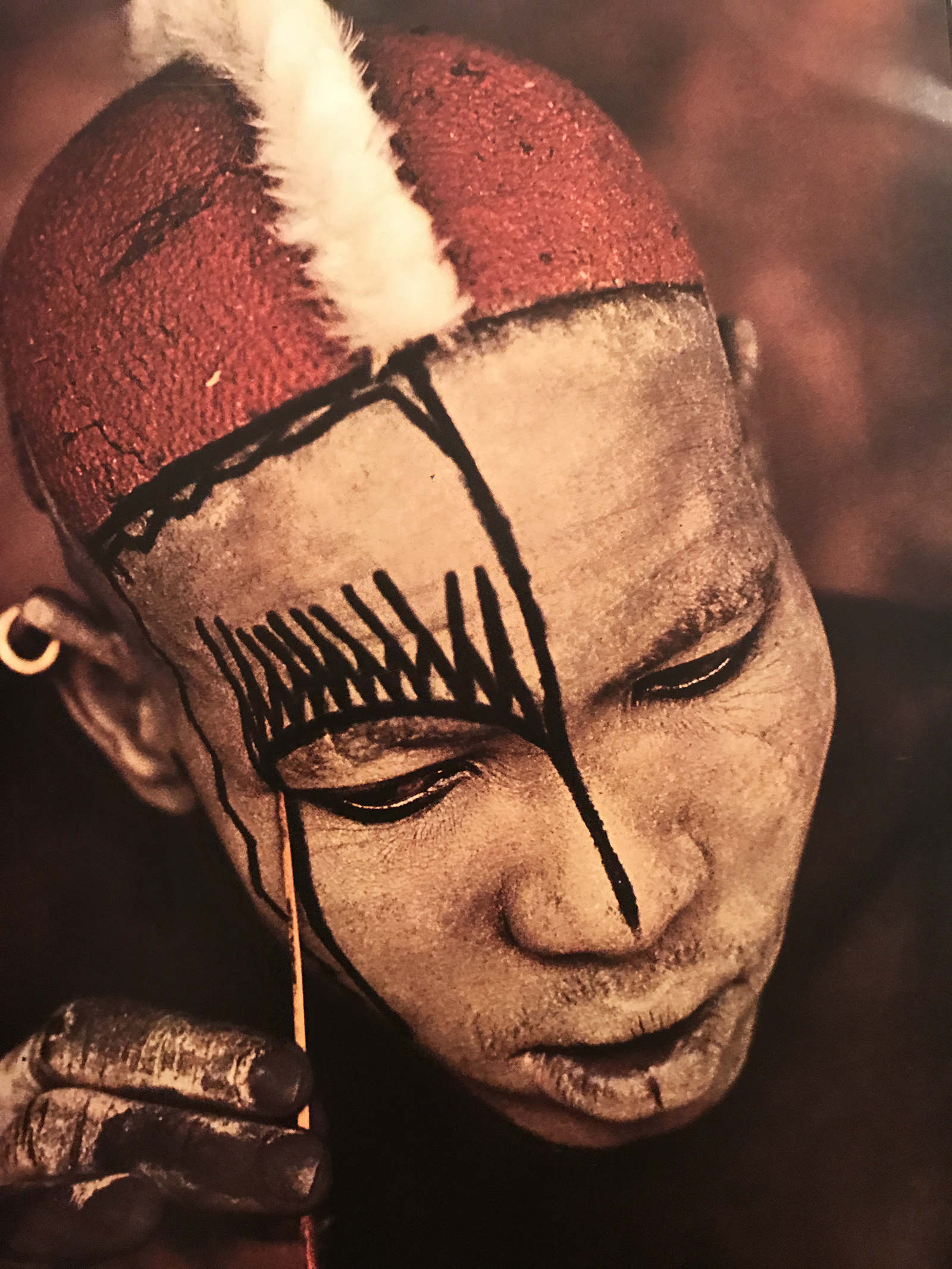

Totemic animals and mandalas also feature prominently as a window into a widespread ‘nature-as-divinity complex’ that appeared to permeate the pysche as a fully formed analogue of scientific knowledge, through sacred geometry and in the form of a shamanic lore that was present across the continent, from Asia, the Steppe region and the Middle East, prior to the rise of the Greek and Roman empires. Commonly these cultures, who fell outside of the cultural boundaries of these empires, were collectively known as ‘pagan’ or ‘barbarian’, yet their knowledge of astrology and medicine were complex, omnipresent and esoterically protected through the use of symbology, sometimes, for example, being articulated through forms of art such as tattooing. These aspects gave rise to the archetype of the wizard, or the magician, who’s origins are traced to Persia and the Middle East as the ‘magi’ of pre-Zoroastrian fire cults.

Dating from around 650AD - 800AD, their symbology reveals the art of early pre-christian Celtic and Germanic peoples which formed the earliest examples of a clear fusion between disparate decorative motifs and designs, aspects of which would later become the Insular style, featuring zoomorphic interlace from the Migration period in western Europe, where pre-existent spiral motifs of Celtic decoration from the Bronze Age, animal and human forms from Pictish stone carving and the woven interlace and keys of Mediterranean origin (source) began to resurface and fuse together as the western part of the Roman Empire almost collapsed.

Although distinctly Christian in context by way of their content, which narrates the four Evangelists (or bringers of good news), their symbolic conceptualisation is undoubtedly pre-christian and astrological in nature.

As ancient historian, Bede explained, in a Christian context, each of the four Evangelists were represented by their own symbol: Matthew was the man, representing the human Christ; Mark was the lion, symbolising the triumphant Christ of the Resurrection; Luke was the calf, symbolising the sacrificial victim of the Crucifixion; and John was the eagle, symbolising Christ's second coming. Collectively they are known as the Tetramorphs, and their symbolism is centred primarily in the knowledge of astrology, with their most popular visual form surviving into modern times as the ‘World’ card of the Tarot‘s Major Arcana.

Although most Insular art originates from the Irish monastic movement of Celtic Christianity, or La Tène metalwork for the secular elite in the period beginning around 600AD, with the combining of Celtic and Anglo-Saxon styles, many of the patterns used for the Lindisfarne Gospels for example, date back to the pre-christian era, possibly even as far back as Egyptian Coptic Christianity (100AD) and the Druidic tradition (100BC) of the British Isles.

The gospels can be interpreted as an accumulation of cultural symbology that were articulated in a time of great political and religious change within the Euopean Dark Ages.

“Nid dim ond duw, Nid duw ond dim.“ (Nothing without God. Without God, only nothing) - Welsh Druidic proverb.

Historically tracable to the region of Wales in around 200BC, the Druidic order was the primary spiritual practice of the Celtic and Gaulish cultures.

As they had no written records, most of what is gleaned about them by modern historians comes through Roman sources, who may have exaggerated elements of their ritual practices of human sacrifice but definitively praised them for their abilities in mathematics and feats of memory, so much so that their power and respect was recognised as a threat to the Roman empire, and their practices outlawed.

The trinity of Evengelions all feature prominent pre-christian, druidic symbology, such as the Triquerta, Wheel of Taranis, Triskelion and Dara Knot. Druidic symbology (and of other animist traditions) often venerated the architecture of the spiral and the cross to relate instrinsically to the conception of God as the uncreated form of universal energy. The processes of measuring this force arguably gave rise to a number of techniques for organising space, such as time-keeping, making astrological alignments and consturcting monolithic monuments based on the spiralling nature of the moon’s journey through the sky. The conception of God, personified in this very same movement, underlies almost all of the visual vocabulary that anicent cultures used to define the forces which remained hidden behind the physcial world, and is expressed in the druidic proverb “Nid dim ond duw, Nid duw ond dim.“ which has the following translations:

There is nothing Uncreated but that which is hidden.

There is nothing not so concievable but that which is immeasurable.

There is no God but that which is Uncreated.

Only the Uncreated is hidden.

Nothing without God, without God no thing.

Totemic animals and mandalas also feature prominently as a window into a widespread ‘nature-as-divinity complex’ that appeared to permeate the pysche as a fully formed analogue of scientific knowledge, through sacred geometry and in the form of a shamanic lore that was present across the continent, from Asia, the Steppe region and the Middle East, prior to the rise of the Greek and Roman empires. Commonly these cultures, who fell outside of the cultural boundaries of these empires, were collectively known as ‘pagan’ or ‘barbarian’, yet their knowledge of astrology and medicine were complex, omnipresent and esoterically protected through the use of symbology, sometimes, for example, being articulated through forms of art such as tattooing. These aspects gave rise to the archetype of the wizard, or the magician, who’s origins are traced to Persia and the Middle East as the ‘magi’ of pre-Zoroastrian fire cults.

Possibly one of the most recognisable books of the trinity of gospels is the Book of Kells, so named after a town in County Meath, Ireland. However, it is thought that monks who inhabited the now relatively isolated island of Iona were the books’ original artists.

Iona, an island of the Inner Hebrides, Scotland, has an interesting history and expansive mythology that also reaches into pre-history. Thought to be originally named ‘Innis nan Druidhneach’ (The Island of the Druids) in Irish Gaelic, ‘Ì nam ban bòidheach’ (Isle of Beautiful Women) in Scottish Gaelic or ‘Ivova’ (Yew Place) in Latin, it has long been associated as a place of animistic learning for pre-christian, pagan sages.

Columba (or Colmcille, meaning Dove) who was the Irish abbot, evangelist and Christian missionary that played an influential role in the production of the Evangelions, moved to Iona in the early 6th Century and founded its Abbey, which became a central power in the conversion of Britain’s pagan inhabitants to the new religion. Columba’s name was self appointed and means ‘Dove of the Church’ in Latin (his Irish birth name being Crimthann, meaning ‘fox’).

It is interesting to note that the original spelling of the word ‘Iona’ in Hebrew and Greek was Yonah, Jehovah, Yonas or John, which also translates to Dove, a common cross-cultural symbol of peace in relation to a complex of attirbutes normally attributed to ancient goddesses. This suggests that the island of Iona already had a pre-existing cultural symbology before Columba’s arrival, which he probably had prior knowledge of.

Another legend attached to Iona that reinforces the connection between the island’s pre-christian history and its ancient, animistic cultural connections is through the Tuatha Dé Danann, a group of people who were recorded in mythical accounts as being early inhabitants of ancient Ireland and Northern Scotland.

The Tuatha Dé Danann‘s associations with eastern spirituality, matrifocal social structure, veneration of the goddess, proto-indo-european linguistic connections and practice of geomancy are embedded in the cultural artefact known as the Lia Fáil (or the Speaking Stone). This stone was apparently brought to Iona by Columba, who then used it as a travelling altar on his missionary activities to the Scottish mainland.

Before this appropriation, as its name suggests, oral accounts of the Speaking Stone describe it as having properties of resonance and healing.

The island of Iona, as well as having a deep spiritual atmosphere that is still felt to this day by Spiritualists and Neo-pagans travelling from the mainland, exhibits a distinct astmospheric change in its geological nature, due to much of Iona consisting of some of the oldest metamorphic rocks on earth, formed over 2,500 million years ago (source) as well as being located close to an ancient fault line.

One of the most notable psycho-geographical studies of the symbology shows clear connections with early Buddhist iconography, suggesting a vast tapestry of animistic and pagan connections that wove disparate cultural traditions together across the Eurasian continent and even out of North Africa (especially from the Carthaginian colonies of the mediterranean people, commonly known as the Phoenicians or Canaanites, who were a sea-faring culture, arriving in the British Isles to trade for its resources of tin).

These connections, which by no means are accepted by all academics, share mythical origins in an era before written histories gave rise to nation states. However, they are further attested to through the Celtic cultural connections with early Hindu and Buddhist animist beliefs, who’s influence can be mapped symbolically and linguistically all the way from India to Denmark via the comparisons of Cernnunos and Pashupati on the Gundestrup cauldron (dated at 200BC).

Etymologically related to the mythical people of Tuatha Dé Danann of Ireland is the ancient water goddess named Danu, who shares her origns in the Vedic traditions of India (source).

The subsequent occupants of Ireland in the following mythical era, known as the Millesians, also had a druidic tradition that in some aspects mirrored the traditions of the Brahmin priests. The well known cultural figure of Amergin - a Millesian druid and bard, is said to have given Ireland its original name ‘Ériu’, after the daughter of a defeated king of the Tuatha Dé Danann. In his poem, the Song of Amergin (which was said to be able to control the movement of rain clouds) has some stylistic features similarly found in the Indian Vedas.

Interpreting mythology as a force through which emanates a recurring symbology of sacred principles, Art Historian, Jacques Guilmain, suggests that although the classification and categorisation of the geometry and motifs contained within the illuminations is an invaluable approach to understanding their significance, their overall compositional effects, of which the individual motifs are an integral part of the whole, should also be taken into consideration, including emphasis and proportional correlations.

Through the symbolism and architecture of the cross and spiral for example, a meditative space opens into an archetypal realm of animism, overflowing with serpents interlaced with birds and vortices of Fylfots (or Swastikas) and Tibetan-looking Gankyil symbols (often referred to in Western Europe as Triskelions).

Guilmain goes on to write that these motifs “are still evident in the latest date of the three books, the Book of Kells, but they are shrouded in a world of decorative richness, intense technical virtuosity, and ‘baroque’ complexity”, perhaps to place new cultural overlays onto the symbology in an effort to diect their influence in an era of newly defined social and religious paradigms.

Iona, an island of the Inner Hebrides, Scotland, has an interesting history and expansive mythology that also reaches into pre-history. Thought to be originally named ‘Innis nan Druidhneach’ (The Island of the Druids) in Irish Gaelic, ‘Ì nam ban bòidheach’ (Isle of Beautiful Women) in Scottish Gaelic or ‘Ivova’ (Yew Place) in Latin, it has long been associated as a place of animistic learning for pre-christian, pagan sages.

Columba (or Colmcille, meaning Dove) who was the Irish abbot, evangelist and Christian missionary that played an influential role in the production of the Evangelions, moved to Iona in the early 6th Century and founded its Abbey, which became a central power in the conversion of Britain’s pagan inhabitants to the new religion. Columba’s name was self appointed and means ‘Dove of the Church’ in Latin (his Irish birth name being Crimthann, meaning ‘fox’).

It is interesting to note that the original spelling of the word ‘Iona’ in Hebrew and Greek was Yonah, Jehovah, Yonas or John, which also translates to Dove, a common cross-cultural symbol of peace in relation to a complex of attirbutes normally attributed to ancient goddesses. This suggests that the island of Iona already had a pre-existing cultural symbology before Columba’s arrival, which he probably had prior knowledge of.

Another legend attached to Iona that reinforces the connection between the island’s pre-christian history and its ancient, animistic cultural connections is through the Tuatha Dé Danann, a group of people who were recorded in mythical accounts as being early inhabitants of ancient Ireland and Northern Scotland.

The Tuatha Dé Danann‘s associations with eastern spirituality, matrifocal social structure, veneration of the goddess, proto-indo-european linguistic connections and practice of geomancy are embedded in the cultural artefact known as the Lia Fáil (or the Speaking Stone). This stone was apparently brought to Iona by Columba, who then used it as a travelling altar on his missionary activities to the Scottish mainland.

Before this appropriation, as its name suggests, oral accounts of the Speaking Stone describe it as having properties of resonance and healing.

The island of Iona, as well as having a deep spiritual atmosphere that is still felt to this day by Spiritualists and Neo-pagans travelling from the mainland, exhibits a distinct astmospheric change in its geological nature, due to much of Iona consisting of some of the oldest metamorphic rocks on earth, formed over 2,500 million years ago (source) as well as being located close to an ancient fault line.

One of the most notable psycho-geographical studies of the symbology shows clear connections with early Buddhist iconography, suggesting a vast tapestry of animistic and pagan connections that wove disparate cultural traditions together across the Eurasian continent and even out of North Africa (especially from the Carthaginian colonies of the mediterranean people, commonly known as the Phoenicians or Canaanites, who were a sea-faring culture, arriving in the British Isles to trade for its resources of tin).

These connections, which by no means are accepted by all academics, share mythical origins in an era before written histories gave rise to nation states. However, they are further attested to through the Celtic cultural connections with early Hindu and Buddhist animist beliefs, who’s influence can be mapped symbolically and linguistically all the way from India to Denmark via the comparisons of Cernnunos and Pashupati on the Gundestrup cauldron (dated at 200BC).

Etymologically related to the mythical people of Tuatha Dé Danann of Ireland is the ancient water goddess named Danu, who shares her origns in the Vedic traditions of India (source).

The subsequent occupants of Ireland in the following mythical era, known as the Millesians, also had a druidic tradition that in some aspects mirrored the traditions of the Brahmin priests. The well known cultural figure of Amergin - a Millesian druid and bard, is said to have given Ireland its original name ‘Ériu’, after the daughter of a defeated king of the Tuatha Dé Danann. In his poem, the Song of Amergin (which was said to be able to control the movement of rain clouds) has some stylistic features similarly found in the Indian Vedas.

Interpreting mythology as a force through which emanates a recurring symbology of sacred principles, Art Historian, Jacques Guilmain, suggests that although the classification and categorisation of the geometry and motifs contained within the illuminations is an invaluable approach to understanding their significance, their overall compositional effects, of which the individual motifs are an integral part of the whole, should also be taken into consideration, including emphasis and proportional correlations.

Through the symbolism and architecture of the cross and spiral for example, a meditative space opens into an archetypal realm of animism, overflowing with serpents interlaced with birds and vortices of Fylfots (or Swastikas) and Tibetan-looking Gankyil symbols (often referred to in Western Europe as Triskelions).

Guilmain goes on to write that these motifs “are still evident in the latest date of the three books, the Book of Kells, but they are shrouded in a world of decorative richness, intense technical virtuosity, and ‘baroque’ complexity”, perhaps to place new cultural overlays onto the symbology in an effort to diect their influence in an era of newly defined social and religious paradigms.

All three Evangelions were considered at somepoint to have been treasure binded - having their covers lavishly decorated with jewells, stones and gold plates. Due to this part of the British Isles being subjected to Viking invasions and political upheaval at the time of the Dark Ages, the original treasure binidngs have since been destroyed or lost. The Lindisfarne Gospels were recreated however, through the literary records that described its original appearance.

The rich decoration of the books are carried out in a wide range of colours drawn from animal, vegetable and mineral sources, some of which were imported over vast distances. Once again, late classical influences from the Mediterranean are blended with Celtic motifs and Germanic animal ornamentation to produce the gospel’s distinctive style. According to studies undertaken by the British Library, “A beaten egg-white preparation called ‘glair’ was used as an adhesive and mixed with pigments. The black ink used for the main text of the gospel is iron gall ink made from oak-galls and iron salts, while a black pigment called lamp black containing particles of carbon was used in the illuminations. Green colours were produced using either verdigris, which is made by suspending copper over vinegar, or vergaut made by mixing blue and yellow pigments.” (source).

The Lindisfarne Gospels are presumed to be the work of a monk named Eadfrith, who became Bishop of Lindisfarne in 698. Eadfrith manufactured ninety of his own colours with "only six local minerals and vegetable extracts". Its also suggested that he "knew about lapis lazuli (a semi-precious stone with a blue tint) from Afghanistan and the Himalayas, but could not get hold of any, and so he made his own" (source).

The copying and decoration of the Lindisfarne Gospels represent a remarkable artistic achievement. The book includes five highly elaborate full-page carpet pages, so-called because of their resemblance to carpets from the eastern Mediterranean.

Either alongside the intricate woven depths of the illuminated manuscripts or twisted inside volutes and tubular typographic forms are animals of everyday life and totemic creatures of another realm who’s spiritual significance was well established in the Middle East and into ancient Europe some one thousand years or more before the Christian era established itself as a dominant socio-political force that changed the character of the psyche.

As Historian of Religion Mircea Eliade described the nature of animistic religions as a kind of pre-conscious connection to nature as a form of divinity, where symbols were ciphers of the potency of unknown forces, stating that “symbols are capable of revealing a modality of the real or a structure of the World that is not evident on the level of immediate experience” (source).

Eliade touches upon the notion of archetypes but also upon a domain of the mind that organises the world as a symbol of a living totality rather than a conceptual, linguistic abstraction that exists in isolation.

The rich decoration of the books are carried out in a wide range of colours drawn from animal, vegetable and mineral sources, some of which were imported over vast distances. Once again, late classical influences from the Mediterranean are blended with Celtic motifs and Germanic animal ornamentation to produce the gospel’s distinctive style. According to studies undertaken by the British Library, “A beaten egg-white preparation called ‘glair’ was used as an adhesive and mixed with pigments. The black ink used for the main text of the gospel is iron gall ink made from oak-galls and iron salts, while a black pigment called lamp black containing particles of carbon was used in the illuminations. Green colours were produced using either verdigris, which is made by suspending copper over vinegar, or vergaut made by mixing blue and yellow pigments.” (source).

The Lindisfarne Gospels are presumed to be the work of a monk named Eadfrith, who became Bishop of Lindisfarne in 698. Eadfrith manufactured ninety of his own colours with "only six local minerals and vegetable extracts". Its also suggested that he "knew about lapis lazuli (a semi-precious stone with a blue tint) from Afghanistan and the Himalayas, but could not get hold of any, and so he made his own" (source).

The copying and decoration of the Lindisfarne Gospels represent a remarkable artistic achievement. The book includes five highly elaborate full-page carpet pages, so-called because of their resemblance to carpets from the eastern Mediterranean.

Either alongside the intricate woven depths of the illuminated manuscripts or twisted inside volutes and tubular typographic forms are animals of everyday life and totemic creatures of another realm who’s spiritual significance was well established in the Middle East and into ancient Europe some one thousand years or more before the Christian era established itself as a dominant socio-political force that changed the character of the psyche.

As Historian of Religion Mircea Eliade described the nature of animistic religions as a kind of pre-conscious connection to nature as a form of divinity, where symbols were ciphers of the potency of unknown forces, stating that “symbols are capable of revealing a modality of the real or a structure of the World that is not evident on the level of immediate experience” (source).

Eliade touches upon the notion of archetypes but also upon a domain of the mind that organises the world as a symbol of a living totality rather than a conceptual, linguistic abstraction that exists in isolation.

“I am a stag: of seven tines,

I am a flood: across a plain,

I am a wind: on a deep lake,

I am a tear: the Sun lets fall,

I am a hawk: above the cliff,

I am a thorn: beneath the nail,

I am a wonder: among flowers,

I am a wizard: who but I

Sets the cool head aflame with smoke?

I am a spear: that roars for blood,

I am a salmon: in a pool,

I am a lure: from paradise,

I am a hill: where poets walk,

I am a boar: ruthless and red,

I am a breaker: threatening doom,

I am a tide: that drags to death,

I am an infant: who but I

Peeps from the unhewn dolmen arch?

I am the womb: of every holt,

I am the blaze: on every hill,

I am the queen: of every hive,

I am the shield: for every head,

I am the tomb: of every hope.”

- ‘Song of Amergin’, translated from the Lebor Gabála Érenn.

I am a flood: across a plain,

I am a wind: on a deep lake,

I am a tear: the Sun lets fall,

I am a hawk: above the cliff,

I am a thorn: beneath the nail,

I am a wonder: among flowers,

I am a wizard: who but I

Sets the cool head aflame with smoke?

I am a spear: that roars for blood,

I am a salmon: in a pool,

I am a lure: from paradise,

I am a hill: where poets walk,

I am a boar: ruthless and red,

I am a breaker: threatening doom,

I am a tide: that drags to death,

I am an infant: who but I

Peeps from the unhewn dolmen arch?

I am the womb: of every holt,

I am the blaze: on every hill,

I am the queen: of every hive,

I am the shield: for every head,

I am the tomb: of every hope.”

- ‘Song of Amergin’, translated from the Lebor Gabála Érenn.

︎Lithograph reproduction by Margaret Stokes, 1861.

︎Animal initials painted by Helen Campbell d’Olier.

The richness of the decoration in the Evangelions, particularly the Book of Kells (800AD), remained relatively unknown until the early decades of the nineteenth century. Reproducing the intricate detail of the artwork posed a considerable challenge, requiring time, patience and a steady hand. Among the earliest artists to undertake the task were two women, Margaret Stokes and Helen Campbell d’Olier.

Margaret Stokes was a highly knowledgeable antiquarian from Dublin, who spent hours poring over the details of the Book of Kells and other Trinity manuscripts which gave her insights that far surpassed those of the academics writing about the art at the time.Helen Campbell d’Olier’s drawings were directly traced from the manuscript, and so the most accurate of the early painted reproductions. She exhibited some of her drawings at the Dublin Exhibition of 1861, and a framed set of her painted animal initials were put on display alongside the manuscript during the early twentieth century (source).

By retracing the line, by following their meanders and their vortices to illuminate the mind and body’s connection to a reality or situation in which human existence is engaged, has always been the necessary existential value of religious symbolism, of which all art, at it’s most subconscious level, is an extension.

As Eliade continues, “Owing to the symbolism of the moon, the World no longer appears as an arbitrary assemblage of heterogeneous and divergent realities. The diverse cosmic levels communicate with each other; they are "bound together" by the same lunar rhythm, just as human life also is "woven together" by the moon and is predestined by the "spinning" goddesses.”

The deeply rooted ancient symbolism of the Evangelions (The Book of Durrow, The Lindisfarne Gospels and The Book of Kells) are yet to reveal all of their wide-reaching cultural secrets beyond their traditional Christian context.

Their visual geometries summon creatures from realms of a forgotten past who possess the rejuvinating qualities of time as a divine substance, uniting cultures within a living image of the sacred. Whilst also retaining their distinct characteristics, they resurrect the original meaning of ‘religion’ as a ‘connection’ or ‘bond’ with the primal movements of nature as a form of identity.

Margaret Stokes was a highly knowledgeable antiquarian from Dublin, who spent hours poring over the details of the Book of Kells and other Trinity manuscripts which gave her insights that far surpassed those of the academics writing about the art at the time.Helen Campbell d’Olier’s drawings were directly traced from the manuscript, and so the most accurate of the early painted reproductions. She exhibited some of her drawings at the Dublin Exhibition of 1861, and a framed set of her painted animal initials were put on display alongside the manuscript during the early twentieth century (source).

By retracing the line, by following their meanders and their vortices to illuminate the mind and body’s connection to a reality or situation in which human existence is engaged, has always been the necessary existential value of religious symbolism, of which all art, at it’s most subconscious level, is an extension.

As Eliade continues, “Owing to the symbolism of the moon, the World no longer appears as an arbitrary assemblage of heterogeneous and divergent realities. The diverse cosmic levels communicate with each other; they are "bound together" by the same lunar rhythm, just as human life also is "woven together" by the moon and is predestined by the "spinning" goddesses.”

The deeply rooted ancient symbolism of the Evangelions (The Book of Durrow, The Lindisfarne Gospels and The Book of Kells) are yet to reveal all of their wide-reaching cultural secrets beyond their traditional Christian context.

Their visual geometries summon creatures from realms of a forgotten past who possess the rejuvinating qualities of time as a divine substance, uniting cultures within a living image of the sacred. Whilst also retaining their distinct characteristics, they resurrect the original meaning of ‘religion’ as a ‘connection’ or ‘bond’ with the primal movements of nature as a form of identity.

Further Reading ︎

Mull and Iona; A Landscape Fashioned by Geology, by David Stephenson.

Iona, Scotland, article, by Philip Carr-Gomm.

Book of Kells, Facimilefinder, article and video.

Sacred-texts, Book of Kells with plate illustrations.

BBC Culture, The Book of Kells, article.

Reproducing the Book of Kells, article.

High North: Cathaginian Exploration of Ireland, article.

List of traditional inks and pigments, artilce.

Digitised Lindisfarne Gospel, British Library, pdf.

Under the Microscope, Lindisfarne Gospel, British Library, article.

Methodological Remarks on the Study of Religious Symbolism, Mercea Eliade, article.

Mull and Iona; A Landscape Fashioned by Geology, by David Stephenson.

Iona, Scotland, article, by Philip Carr-Gomm.

Book of Kells, Facimilefinder, article and video.

Sacred-texts, Book of Kells with plate illustrations.

BBC Culture, The Book of Kells, article.

Reproducing the Book of Kells, article.

High North: Cathaginian Exploration of Ireland, article.

List of traditional inks and pigments, artilce.

Digitised Lindisfarne Gospel, British Library, pdf.

Under the Microscope, Lindisfarne Gospel, British Library, article.

Methodological Remarks on the Study of Religious Symbolism, Mercea Eliade, article.

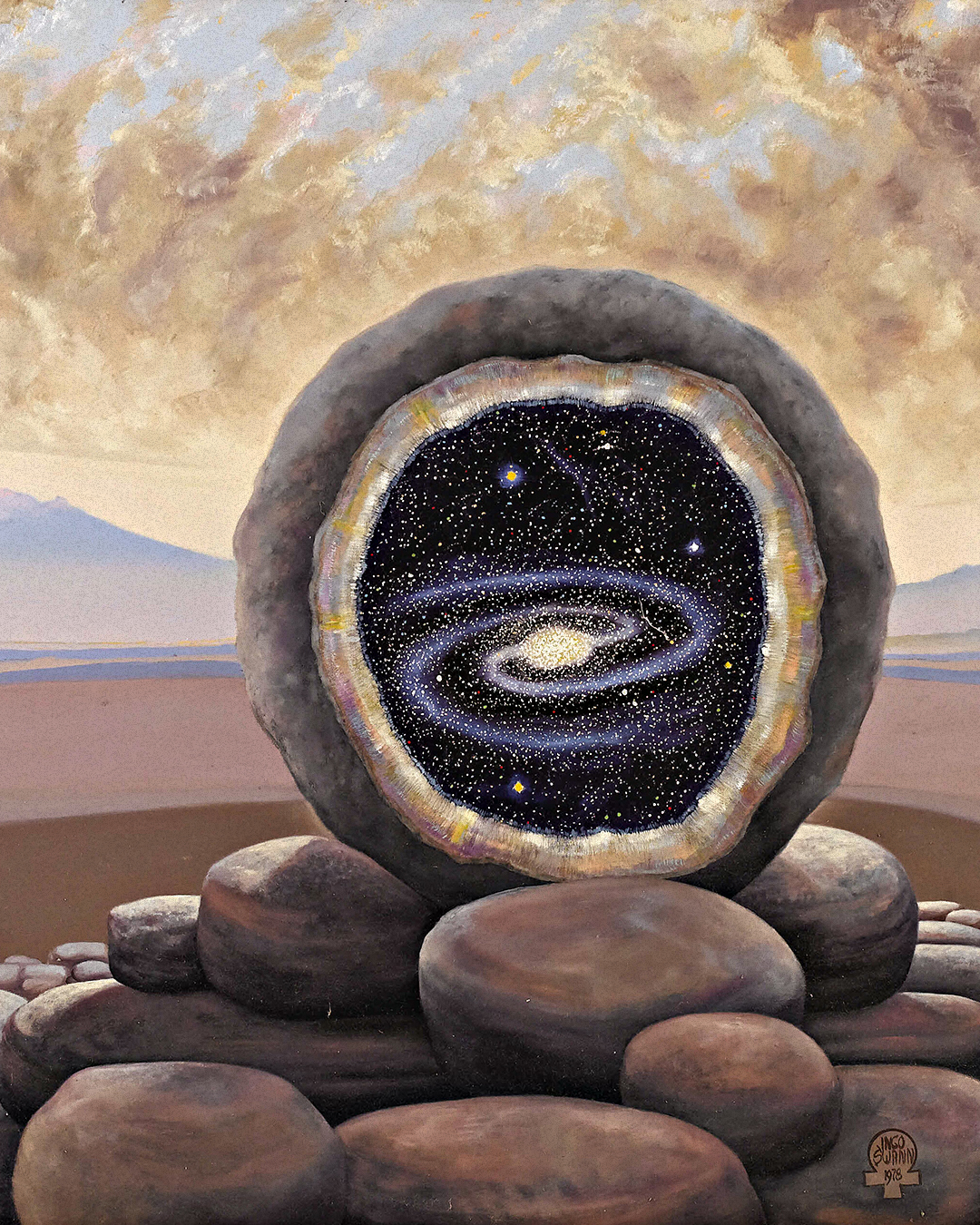

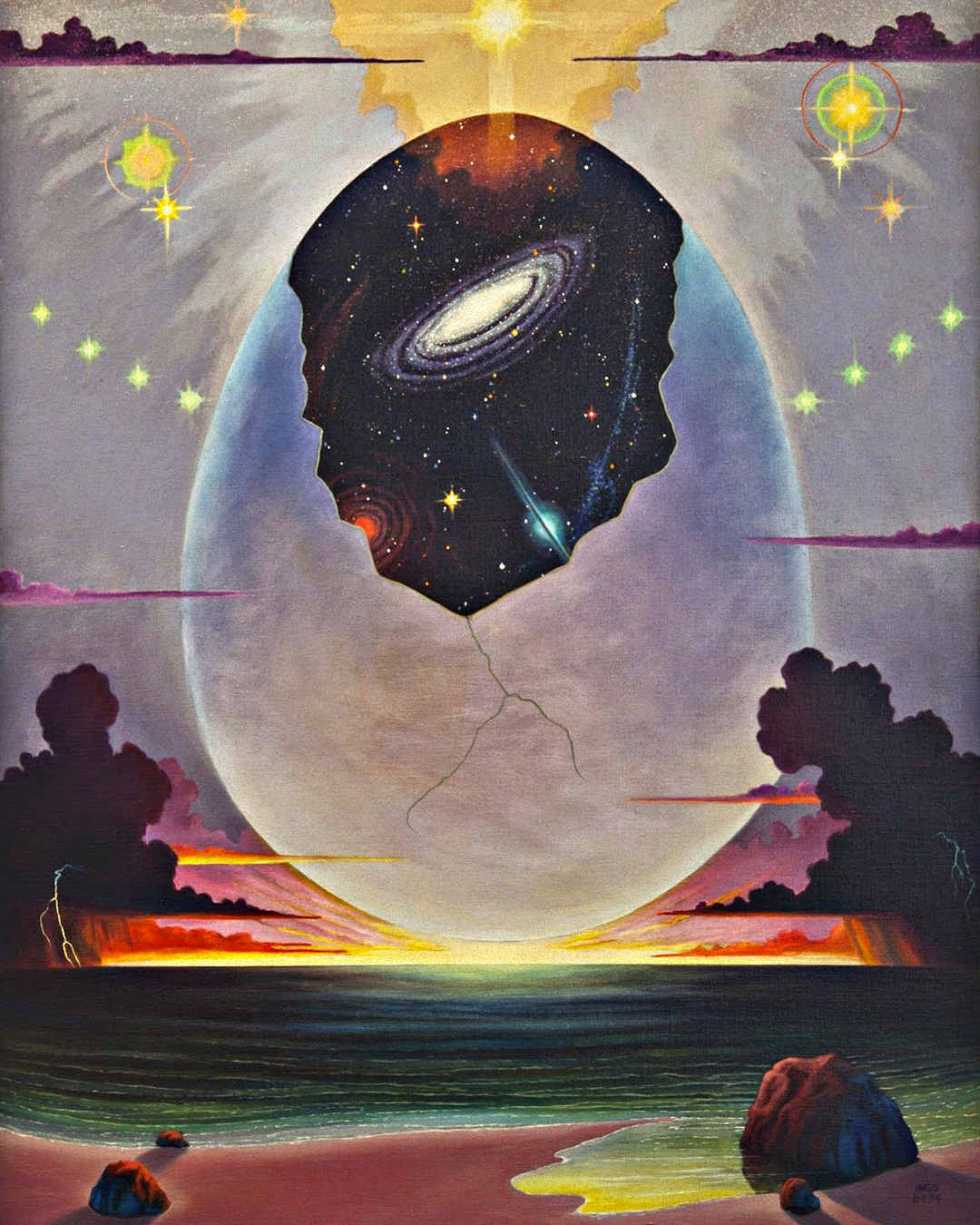

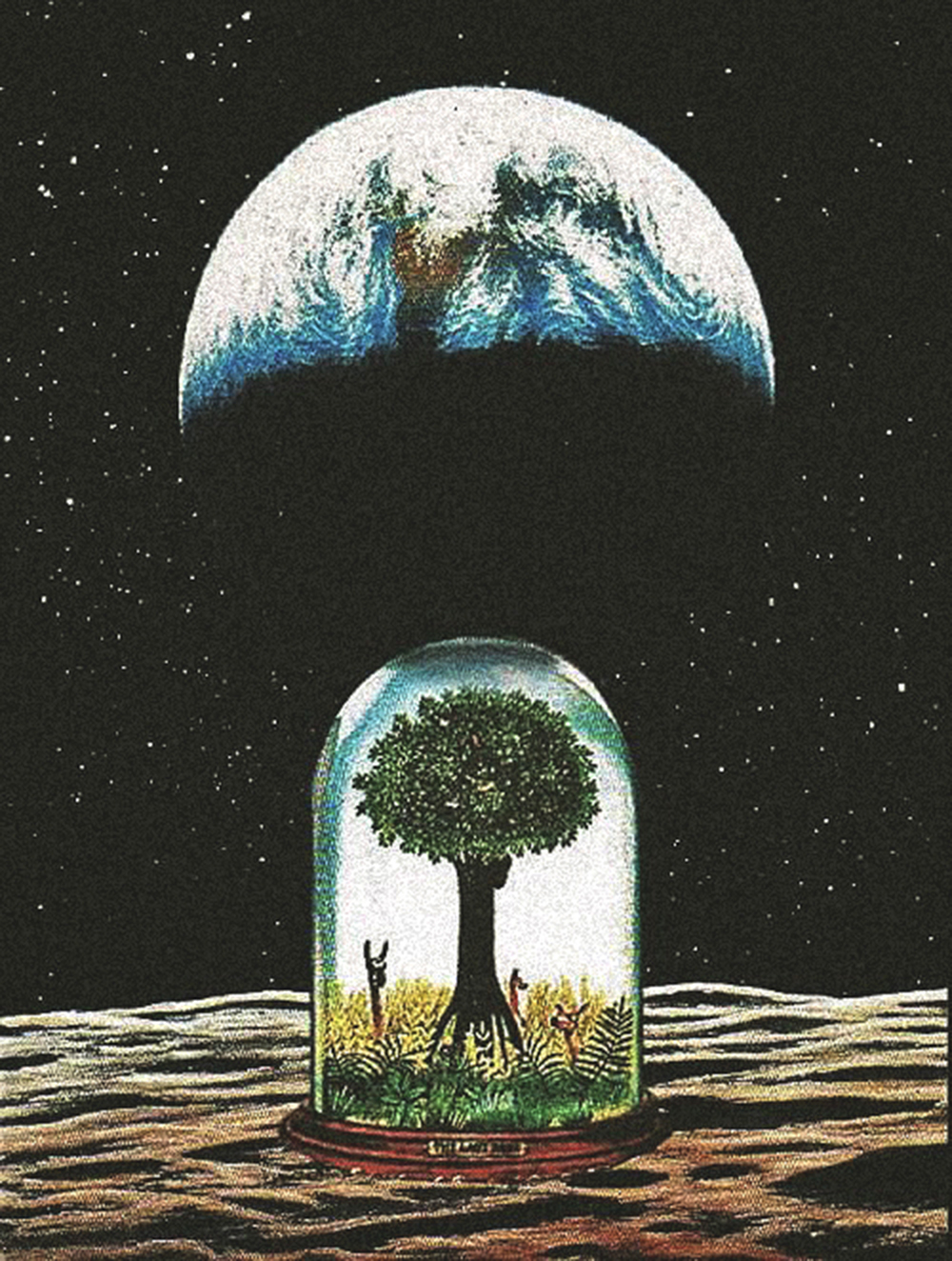

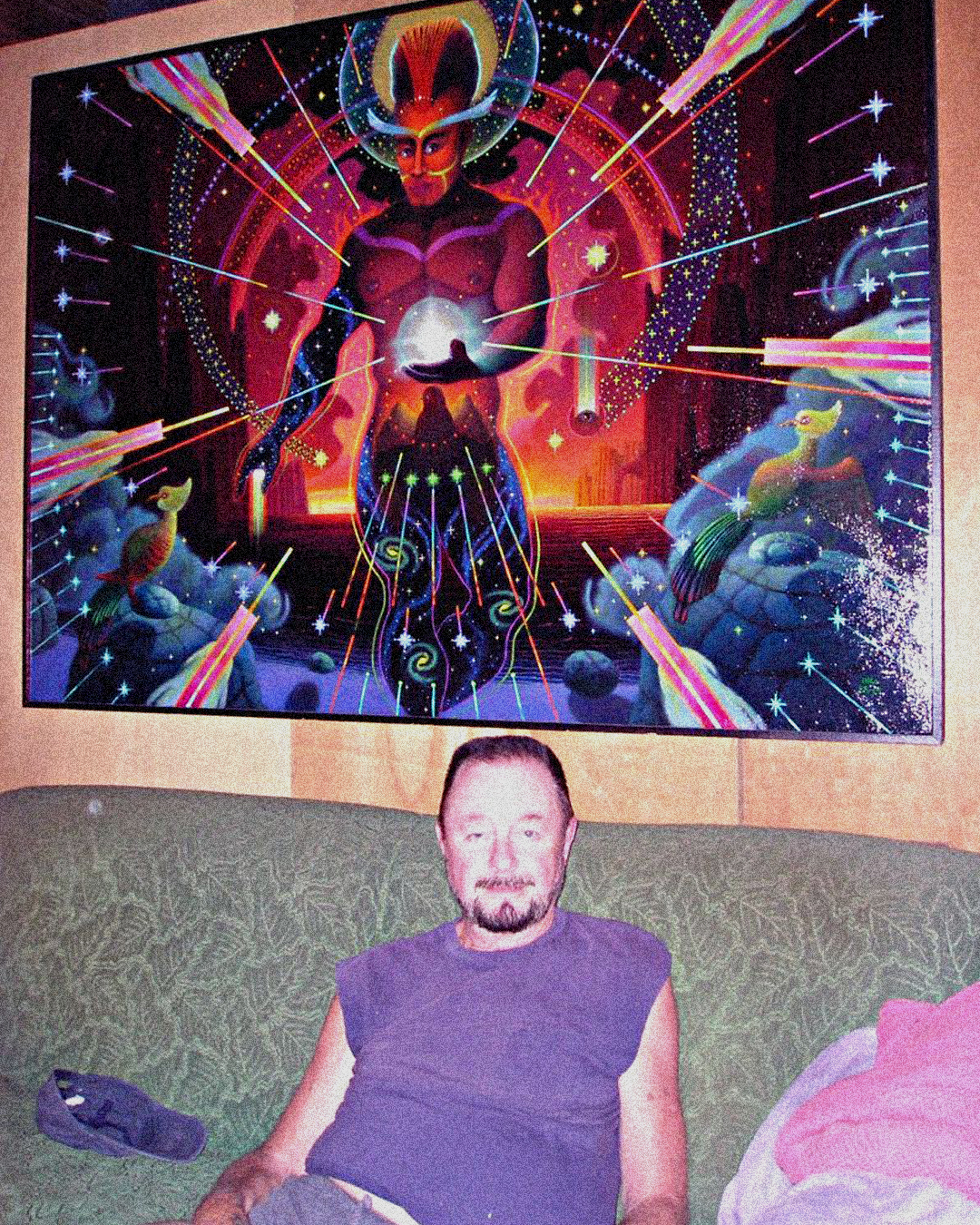

ingo swann

︎Artist, Painting, Spirituality.

︎ Ventral Is Golden

ingo swann

︎Artist, Painting, Spirituality.

︎ Ventral Is Golden

︎ Ventral Is Golden

"The future always foreshadows itself."

Ingo Swann (1933 - 2013) was a visionary artist and renowned for being a pioneer of the technique of ‘remote viewing’ (awareness of distant objects or places through extra sensory perception) at the Stanford Research Institute during the height of the Cold War.

Alongside renowned researchers and physicist, such as Harold Puthoff and Russell Targ, their project, code-named ‘Project Stargate’, ran from 1978 - 1995 and was entirely funded by the CIA with the aim of developing psychic abilities.

Some of Swann’s most notable discoveries using Extra Sensory Perception were describing, in 1973, Jupiter’s rings and the presence of rotating storms and ice crystals in its atmosphere, years before NASA confirmed their existence, as well as successfully locating terrestrial targets such as Soviet spy planes for the U.S Department of Defence.

Alongside renowned researchers and physicist, such as Harold Puthoff and Russell Targ, their project, code-named ‘Project Stargate’, ran from 1978 - 1995 and was entirely funded by the CIA with the aim of developing psychic abilities.

Some of Swann’s most notable discoveries using Extra Sensory Perception were describing, in 1973, Jupiter’s rings and the presence of rotating storms and ice crystals in its atmosphere, years before NASA confirmed their existence, as well as successfully locating terrestrial targets such as Soviet spy planes for the U.S Department of Defence.

Perhaps Swann’s most peculiar discovery whilst remote viewing was described in one of his books entitled, ‘Penetration: The Question of Extraterrestrial and Human Telepathy’ (1998), where he states that whilst employed by a covert, ‘deep black’ CIA operation, he was tasked to explore a possible colony on the dark side of the moon.

Although laregly thought to be fictionalised accounts, in 2006, classified files on the Stargate Project were released and confirmed many of Swann’s collaborations with the CIA.

Regarding the presence of extra-terrestrials on the moon, Swann stated that “not only are they already here, they are also building something”.

After being hypnotised by a secret agent known only as Mr. Axelrod, Swann was given various locations on the moon’s surface to remote view.

Upon reviewing the last location, Swann described seeing what appeared to be track marks leading towards a crater that was filled with a greenish haze of diffused light. At the centre of the crater were some kind of domed structures with windows. Swann moved closer and describes seeing humanoid figures inside who were working on something technical. Then, all of sudden, one of the beings, then two, then a dozen or more, stopped what they were doing and turned to the window where Swann had projected himself.

Swann said aloud, “They see me”.

Mr. Axelrod replied, “Come back, come back now.”

“They’re pointing at me”, Swann said.

Mr. Axelrod told Swann firmly, “Please come back, away from that place.”

Swann returned his consciousness back into the room and opened his eyes. He turned to Mr. Axelrod and said, “You already know they’re psychic, don’t you”.

“The experiment has now ended”, replied Mr. Axelrod.

Throughout his later life, Ingo Swann rarely made public appearances due to the media isolating his powers as a special case. He preferred instead to live out of the public eye, alongside his pet chinchilla, focussing on painting his visionary artworks to encourage others to reconnect to the energy of themselves and the cosmos in the hope that people would cultivate their innate psychic abilities.

Although laregly thought to be fictionalised accounts, in 2006, classified files on the Stargate Project were released and confirmed many of Swann’s collaborations with the CIA.

Regarding the presence of extra-terrestrials on the moon, Swann stated that “not only are they already here, they are also building something”.

After being hypnotised by a secret agent known only as Mr. Axelrod, Swann was given various locations on the moon’s surface to remote view.

Upon reviewing the last location, Swann described seeing what appeared to be track marks leading towards a crater that was filled with a greenish haze of diffused light. At the centre of the crater were some kind of domed structures with windows. Swann moved closer and describes seeing humanoid figures inside who were working on something technical. Then, all of sudden, one of the beings, then two, then a dozen or more, stopped what they were doing and turned to the window where Swann had projected himself.

Swann said aloud, “They see me”.

Mr. Axelrod replied, “Come back, come back now.”

“They’re pointing at me”, Swann said.

Mr. Axelrod told Swann firmly, “Please come back, away from that place.”

Swann returned his consciousness back into the room and opened his eyes. He turned to Mr. Axelrod and said, “You already know they’re psychic, don’t you”.

“The experiment has now ended”, replied Mr. Axelrod.

Throughout his later life, Ingo Swann rarely made public appearances due to the media isolating his powers as a special case. He preferred instead to live out of the public eye, alongside his pet chinchilla, focussing on painting his visionary artworks to encourage others to reconnect to the energy of themselves and the cosmos in the hope that people would cultivate their innate psychic abilities.

“To a large extent, creativity is self-generated in areas of the mind beyond or beneath the individual’s willful, conscious control. All he can do is discipline his consciousness to accommodate the needs of the creative process.” - Ingo Swann.

“This archaic form of telepathy might not undergo conscious development in individuals, but it still remains in the collective unconscious where it continues to exist and react as a non- conscious responsive source of “reciprocal influence” within all individuals of the species.” - Ingo Swann.

sanxingdui

︎Sculpture, Spirituality, Article

︎ Ventral Is Golden

sanxingdui

︎Sculpture, Spirituality, Article

︎ Ventral Is Golden

︎ Ventral Is Golden

“The ancient Masters were profound and subtle. Their wisdom was unfathomable. There is no way to describe it; all we can describe is their appearance. They were careful as someone crossing an icy stream. Alert as a warrior in enemy territory. Courteous as a guest. Fluid as melting ice. Shapable as a block of wood. Receptive as a valley. Clear as a glass of water.” - Lao Tzu.

Since recorded history to the present day, it has been the foundation and source of a country’s power, both in spiritual and military terms, to centralise its mythic tradition so that a national identity can be venerated via an origin story, and maintained to shape the consciousness of a particular region and its people.

There have been many theories suggesting how the development of consciousness through to the rise of modern civilisations has taken place, from Julian Jayne’s Bicameral Mind - a kind of non-conscious, mythic sensibility that is experienced as the ‘voice of god’ in the mind of pre-literate societies, to Karl Jaspers’ Axial Age - a suggested turning point in the history of philosophy, from around 500BC, that saw the emergence of cultural figures rise almost simultaneously across the Eurasian continent, with the likes of Lao-Tzu writing the Tao te Ching in China, the Buddha formulating the Upanishads across India and the subsequent rise of Buddhism and Hindusim through the subcontinent, to Zarathustra and the Avestas in Iran and the Persian Empire, to ancient Greece, where the likes of Homer, Plato, Parmenides and Heraclitus were shaping cultural thought.

Across the Eurasian continent, the break down of tribal communities and their reconstruction into new forms of institutional patterns were taking place. Overall these phenomena were experienced in a multitude of different forms but culminated in what Jaspers thought of as ‘a basis for a theory of universal history’ that lead to a transcendental breakthrough toward a ‘consciousness-of-being’ as a whole, and to self-consciousness in general (source) - a moment in historical time when old certainties had lost their validity and new ones were still in the process of being made.

The late anarchist anthropologist, David Graeber once suggested that the rise of these Axial Age thinkers also corresponded with the introduction of coinage, particularly in areas where these cultural figures were received.

In his essay on ‘Culture as Creative Refusal’, Graeber goes onto say that we tend to assume that so called ‘primitive’ cultures (prior to the institutions of the Axial Age) were somehow primordial or, at best, the product of some deep but ultimately arbitrary cultural matrix, but certainly not a self-conscious political project on the part of actors just as mature and sophisticated as modern-day people.

Rather, Graeber is suggesitng that these early cultures were consciously self-defining as a form of refusal to integrate into larger urban centres.

Furthermore, Graeber elucidates a phenomena, scattered across a band of territory that runs from roughly the Danube to the Ganges, where treasure troves full of large amounts of extremely valuable metalware that appear to have been self-consciously abandoned or even systematically destroyed always seem to appear where cultures mysteriously disappear. The remarkable thing is that such troves never occur within the great urban civilisations themselves, but always in the surrounding marginal zones that were closely connected to the commercial and bureaucratic centres by trade but were in no sense incorporated, and the recently discovered sacrificial pits of the ancient Sanxingdui culture in modern day China are no exception to this trend.

There have been many theories suggesting how the development of consciousness through to the rise of modern civilisations has taken place, from Julian Jayne’s Bicameral Mind - a kind of non-conscious, mythic sensibility that is experienced as the ‘voice of god’ in the mind of pre-literate societies, to Karl Jaspers’ Axial Age - a suggested turning point in the history of philosophy, from around 500BC, that saw the emergence of cultural figures rise almost simultaneously across the Eurasian continent, with the likes of Lao-Tzu writing the Tao te Ching in China, the Buddha formulating the Upanishads across India and the subsequent rise of Buddhism and Hindusim through the subcontinent, to Zarathustra and the Avestas in Iran and the Persian Empire, to ancient Greece, where the likes of Homer, Plato, Parmenides and Heraclitus were shaping cultural thought.

Across the Eurasian continent, the break down of tribal communities and their reconstruction into new forms of institutional patterns were taking place. Overall these phenomena were experienced in a multitude of different forms but culminated in what Jaspers thought of as ‘a basis for a theory of universal history’ that lead to a transcendental breakthrough toward a ‘consciousness-of-being’ as a whole, and to self-consciousness in general (source) - a moment in historical time when old certainties had lost their validity and new ones were still in the process of being made.

The late anarchist anthropologist, David Graeber once suggested that the rise of these Axial Age thinkers also corresponded with the introduction of coinage, particularly in areas where these cultural figures were received.

In his essay on ‘Culture as Creative Refusal’, Graeber goes onto say that we tend to assume that so called ‘primitive’ cultures (prior to the institutions of the Axial Age) were somehow primordial or, at best, the product of some deep but ultimately arbitrary cultural matrix, but certainly not a self-conscious political project on the part of actors just as mature and sophisticated as modern-day people.

Rather, Graeber is suggesitng that these early cultures were consciously self-defining as a form of refusal to integrate into larger urban centres.

Furthermore, Graeber elucidates a phenomena, scattered across a band of territory that runs from roughly the Danube to the Ganges, where treasure troves full of large amounts of extremely valuable metalware that appear to have been self-consciously abandoned or even systematically destroyed always seem to appear where cultures mysteriously disappear. The remarkable thing is that such troves never occur within the great urban civilisations themselves, but always in the surrounding marginal zones that were closely connected to the commercial and bureaucratic centres by trade but were in no sense incorporated, and the recently discovered sacrificial pits of the ancient Sanxingdui culture in modern day China are no exception to this trend.

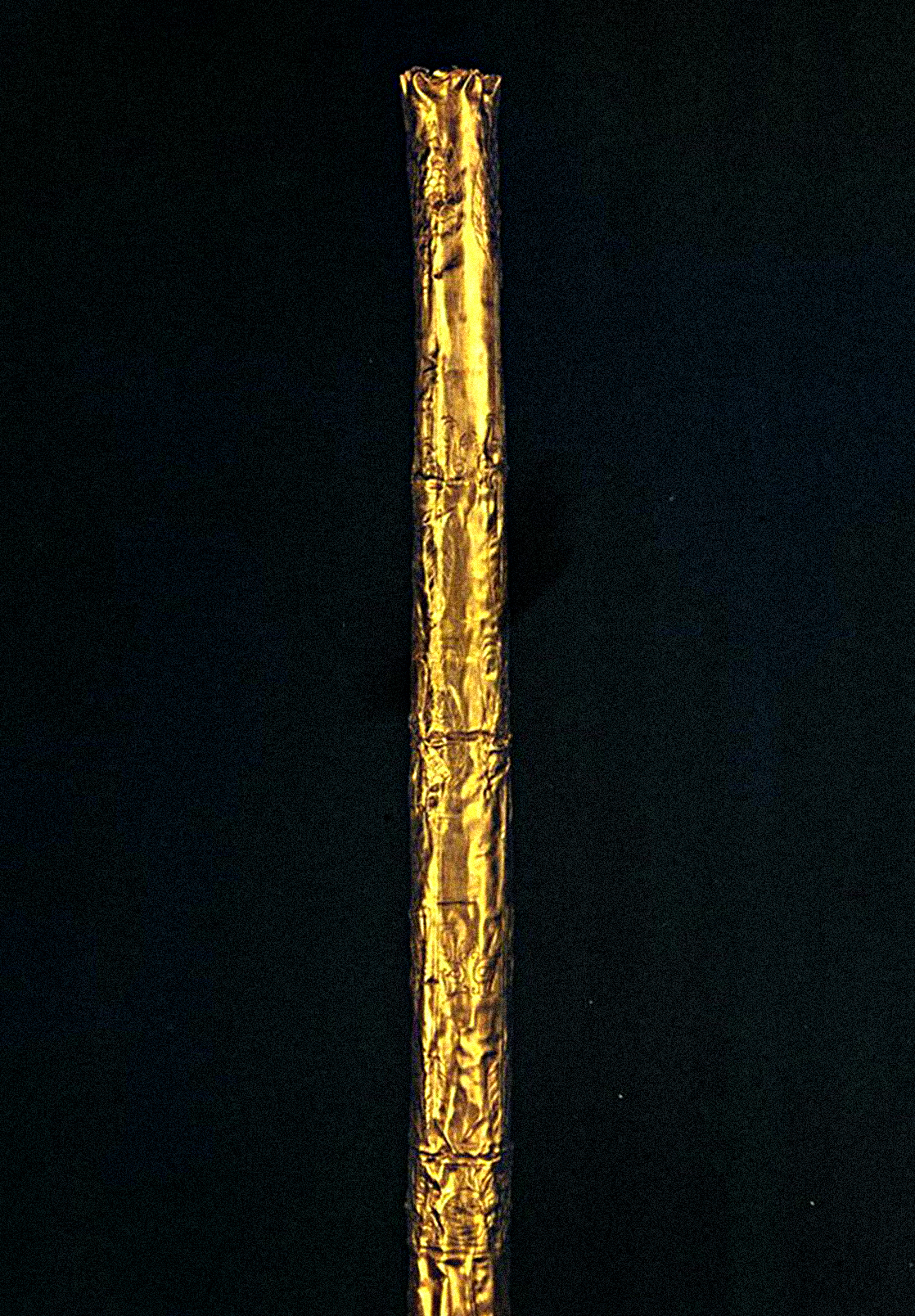

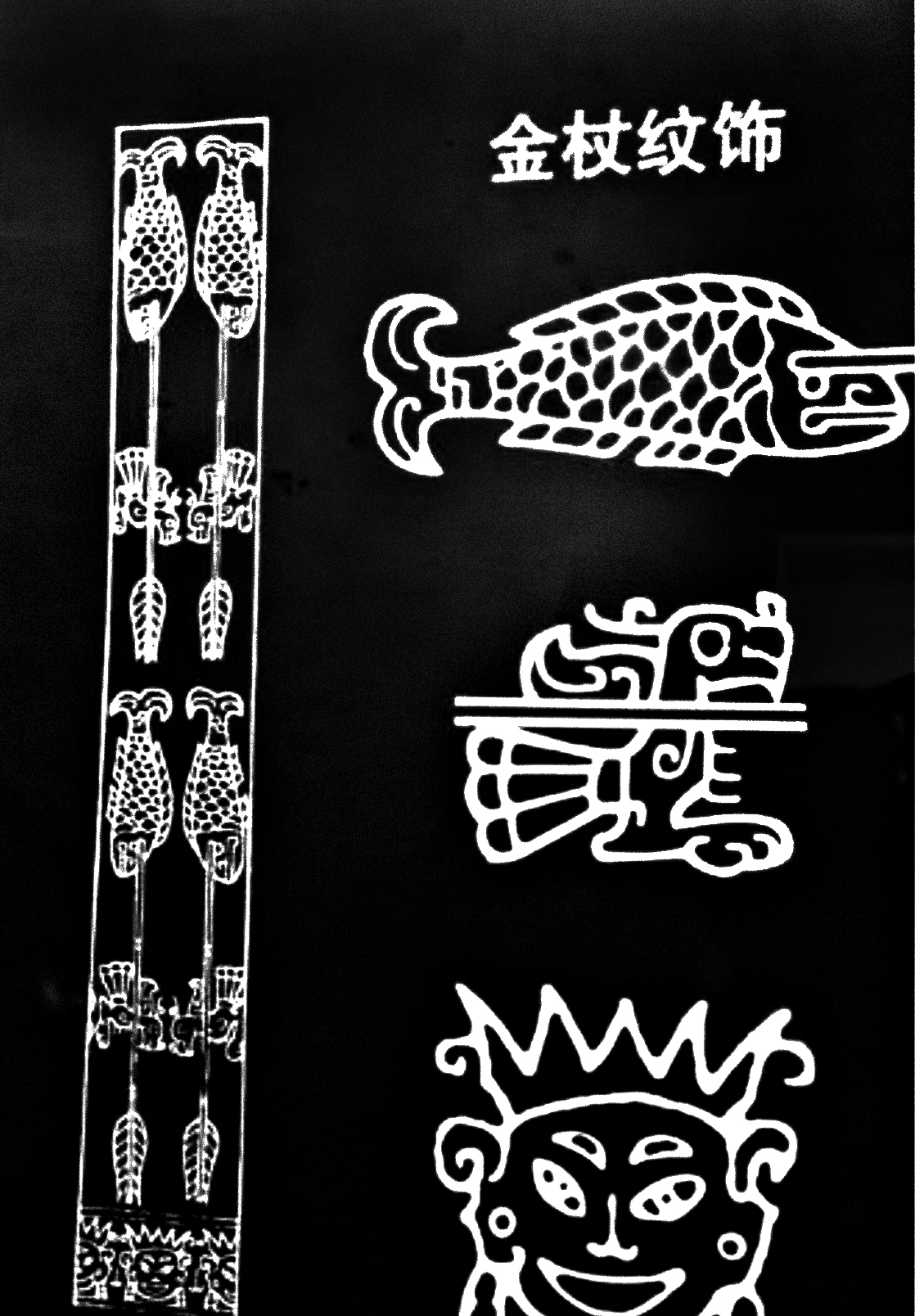

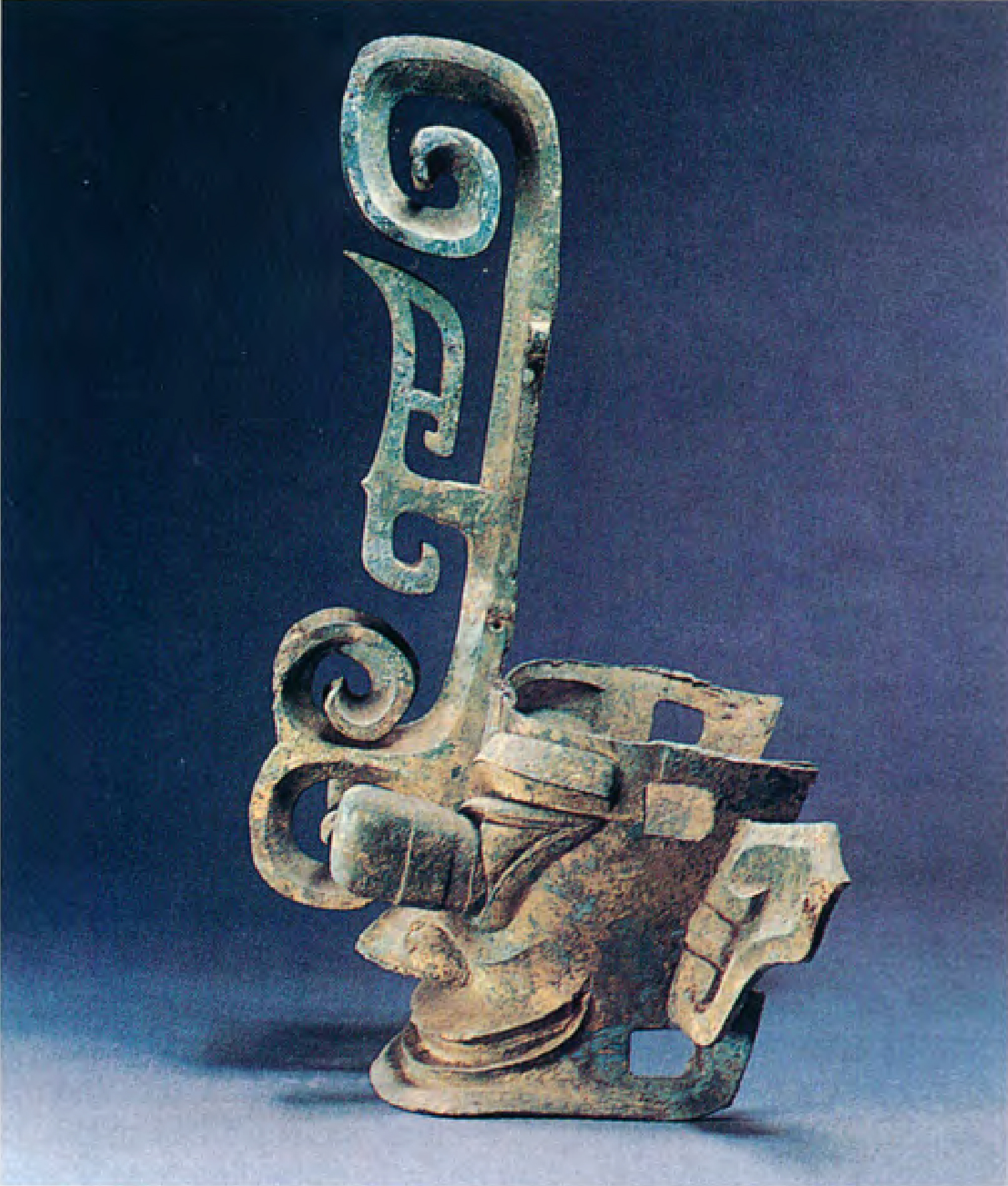

︎ Sacrificial pits containing relics and elephant tusks.