evangelions

︎Culture, Spirituality, Article

︎ Ventral Is Golden

evangelions

︎Culture, Spirituality, Article

︎ Ventral Is Golden

︎ Ventral Is Golden

"All the gods, all the heavens, all the world, are within us. They are magnified dreams, and dreams are manifestations in image form of the energies of the body." - Joseph Campbell.

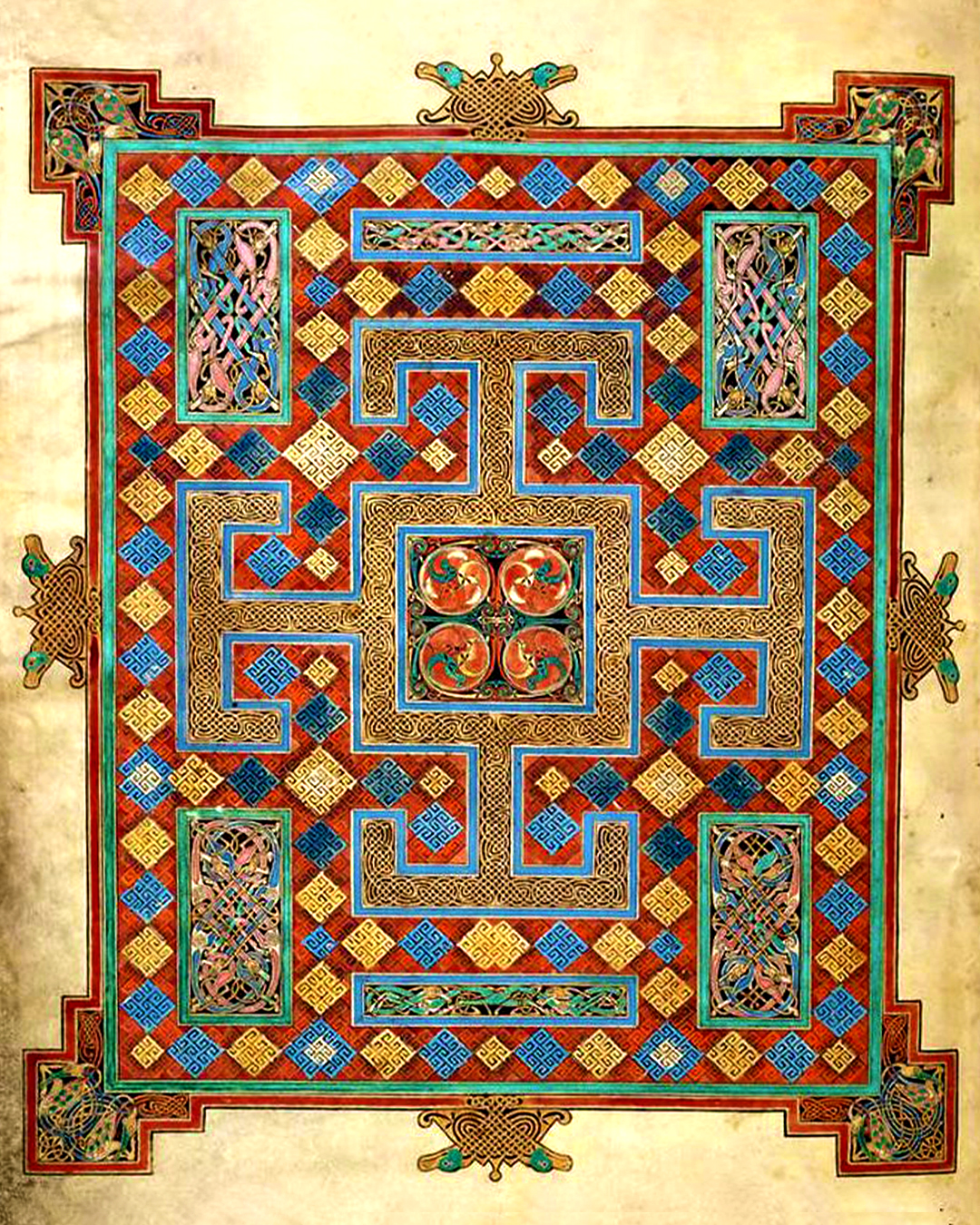

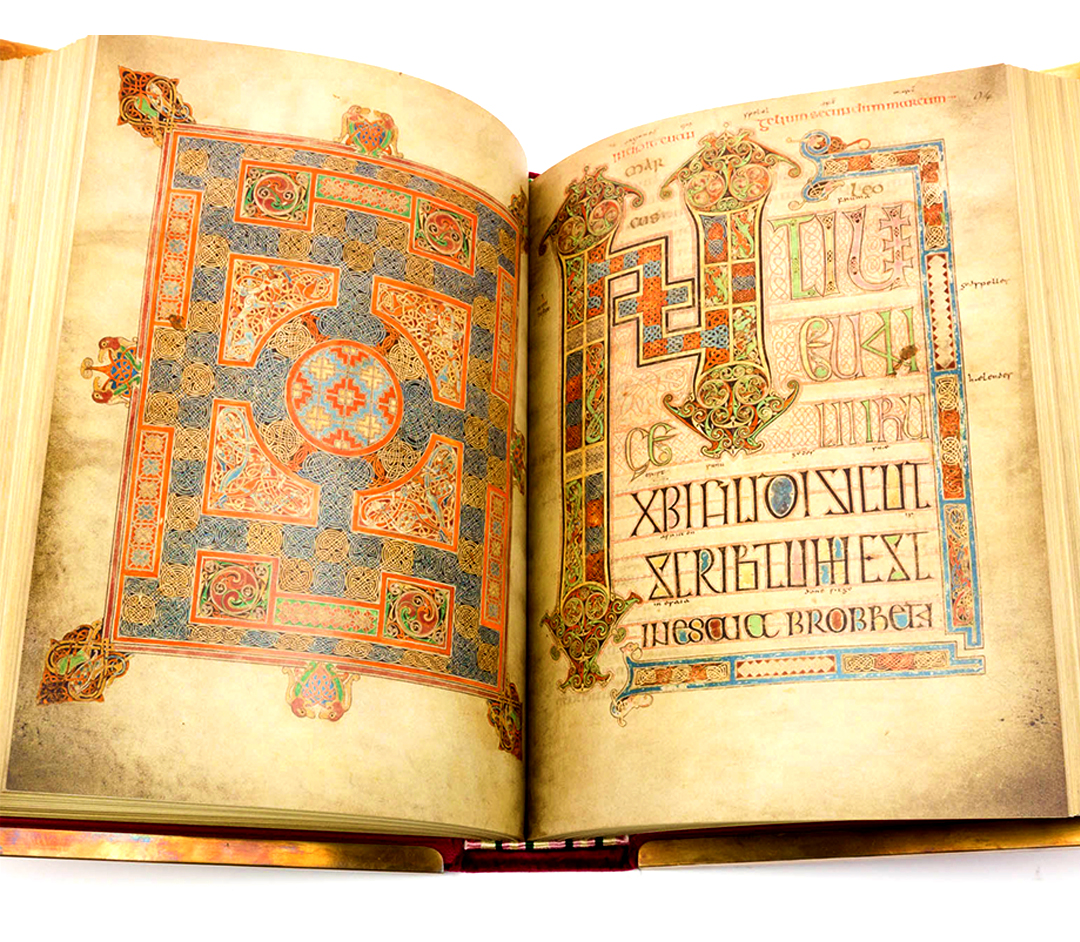

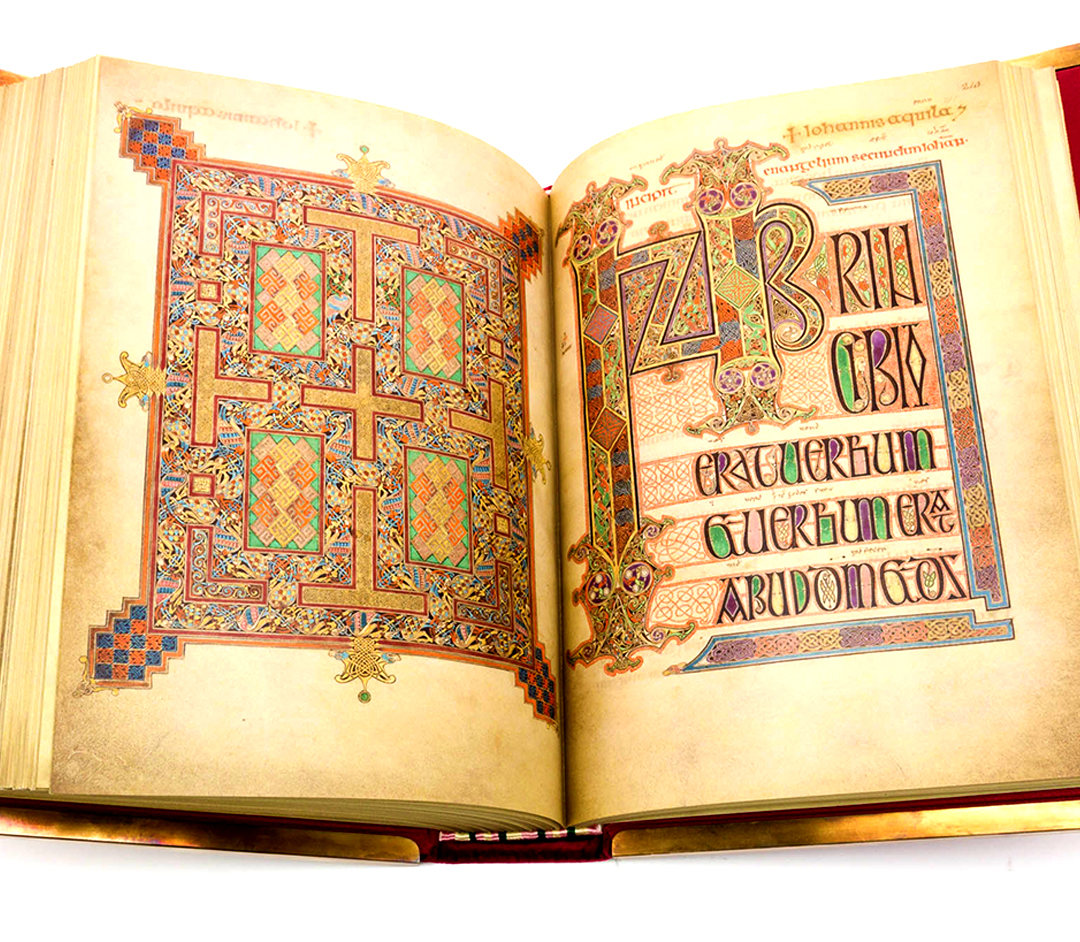

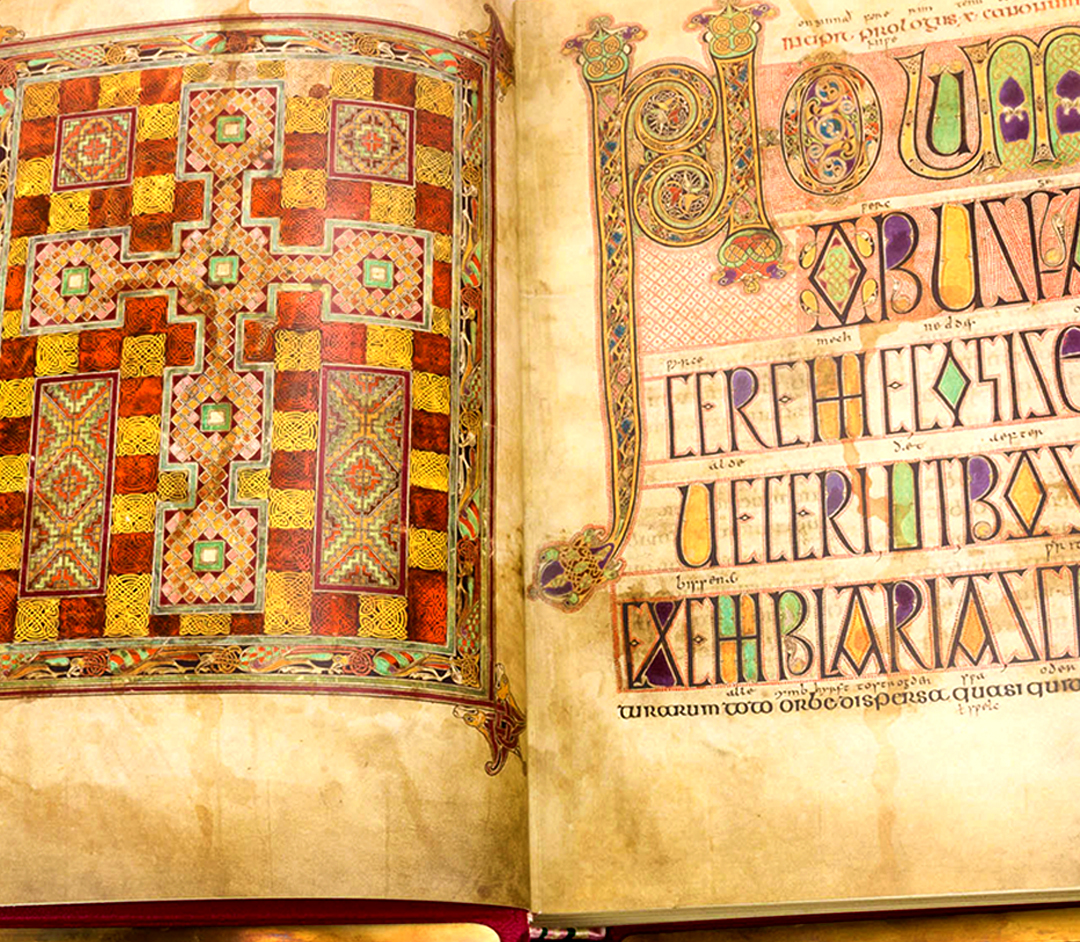

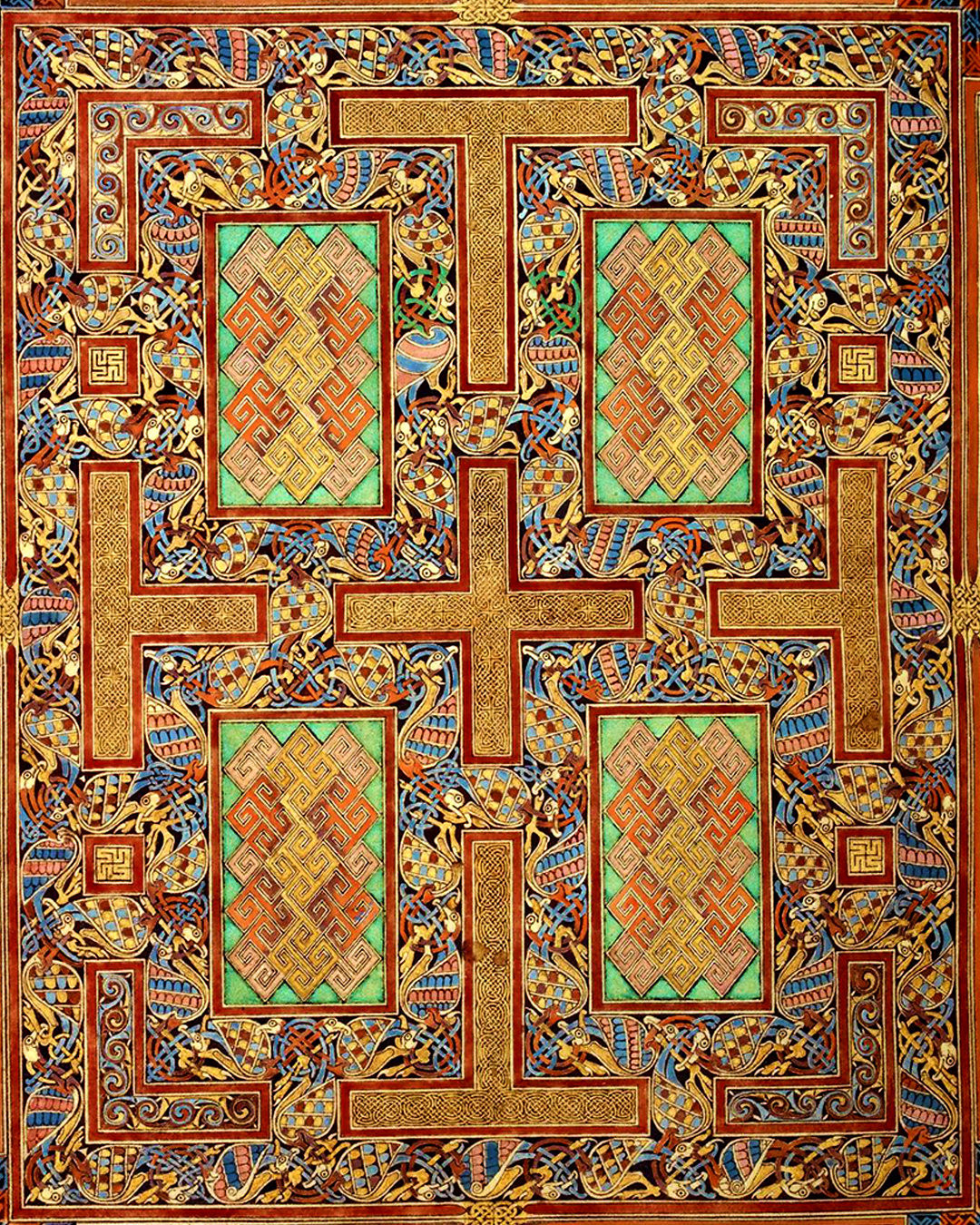

The trilogy of Evengelions (or Gospel Books) known individually from the British Isles as the Book of Durrow, the Lindisfarne Gospels and the Book of Kells, are some of the most intricate examples of art from medieval Europe and are renowned for their cultural significance, production techniques, treasure binding, typographic composition and ‘carpet pages’.

Dating from around 650AD - 800AD, their symbology reveals the art of early pre-christian Celtic and Germanic peoples which formed the earliest examples of a clear fusion between disparate decorative motifs and designs, aspects of which would later become the Insular style, featuring zoomorphic interlace from the Migration period in western Europe, where pre-existent spiral motifs of Celtic decoration from the Bronze Age, animal and human forms from Pictish stone carving and the woven interlace and keys of Mediterranean origin (source) began to resurface and fuse together as the western part of the Roman Empire almost collapsed.

Although distinctly Christian in context by way of their content, which narrates the four Evangelists (or bringers of good news), their symbolic conceptualisation is undoubtedly pre-christian and astrological in nature.

As ancient historian, Bede explained, in a Christian context, each of the four Evangelists were represented by their own symbol: Matthew was the man, representing the human Christ; Mark was the lion, symbolising the triumphant Christ of the Resurrection; Luke was the calf, symbolising the sacrificial victim of the Crucifixion; and John was the eagle, symbolising Christ's second coming. Collectively they are known as the Tetramorphs, and their symbolism is centred primarily in the knowledge of astrology, with their most popular visual form surviving into modern times as the ‘World’ card of the Tarot‘s Major Arcana.

Although most Insular art originates from the Irish monastic movement of Celtic Christianity, or La Tène metalwork for the secular elite in the period beginning around 600AD, with the combining of Celtic and Anglo-Saxon styles, many of the patterns used for the Lindisfarne Gospels for example, date back to the pre-christian era, possibly even as far back as Egyptian Coptic Christianity (100AD) and the Druidic tradition (100BC) of the British Isles.

The gospels can be interpreted as an accumulation of cultural symbology that were articulated in a time of great political and religious change within the Euopean Dark Ages.

Historically tracable to the region of Wales in around 200BC, the Druidic order was the primary spiritual practice of the Celtic and Gaulish cultures.

As they had no written records, most of what is gleaned about them by modern historians comes through Roman sources, who may have exaggerated elements of their ritual practices of human sacrifice but definitively praised them for their abilities in mathematics and feats of memory, so much so that their power and respect was recognised as a threat to the Roman empire, and their practices outlawed.

The trinity of Evengelions all feature prominent pre-christian, druidic symbology, such as the Triquerta, Wheel of Taranis, Triskelion and Dara Knot. Druidic symbology (and of other animist traditions) often venerated the architecture of the spiral and the cross to relate instrinsically to the conception of God as the uncreated form of universal energy. The processes of measuring this force arguably gave rise to a number of techniques for organising space, such as time-keeping, making astrological alignments and consturcting monolithic monuments based on the spiralling nature of the moon’s journey through the sky. The conception of God, personified in this very same movement, underlies almost all of the visual vocabulary that anicent cultures used to define the forces which remained hidden behind the physcial world, and is expressed in the druidic proverb “Nid dim ond duw, Nid duw ond dim.“ which has the following translations:

There is nothing Uncreated but that which is hidden.

There is nothing not so concievable but that which is immeasurable.

There is no God but that which is Uncreated.

Only the Uncreated is hidden.

Nothing without God, without God no thing.

Totemic animals and mandalas also feature prominently as a window into a widespread ‘nature-as-divinity complex’ that appeared to permeate the pysche as a fully formed analogue of scientific knowledge, through sacred geometry and in the form of a shamanic lore that was present across the continent, from Asia, the Steppe region and the Middle East, prior to the rise of the Greek and Roman empires. Commonly these cultures, who fell outside of the cultural boundaries of these empires, were collectively known as ‘pagan’ or ‘barbarian’, yet their knowledge of astrology and medicine were complex, omnipresent and esoterically protected through the use of symbology, sometimes, for example, being articulated through forms of art such as tattooing. These aspects gave rise to the archetype of the wizard, or the magician, who’s origins are traced to Persia and the Middle East as the ‘magi’ of pre-Zoroastrian fire cults.

Dating from around 650AD - 800AD, their symbology reveals the art of early pre-christian Celtic and Germanic peoples which formed the earliest examples of a clear fusion between disparate decorative motifs and designs, aspects of which would later become the Insular style, featuring zoomorphic interlace from the Migration period in western Europe, where pre-existent spiral motifs of Celtic decoration from the Bronze Age, animal and human forms from Pictish stone carving and the woven interlace and keys of Mediterranean origin (source) began to resurface and fuse together as the western part of the Roman Empire almost collapsed.

Although distinctly Christian in context by way of their content, which narrates the four Evangelists (or bringers of good news), their symbolic conceptualisation is undoubtedly pre-christian and astrological in nature.

As ancient historian, Bede explained, in a Christian context, each of the four Evangelists were represented by their own symbol: Matthew was the man, representing the human Christ; Mark was the lion, symbolising the triumphant Christ of the Resurrection; Luke was the calf, symbolising the sacrificial victim of the Crucifixion; and John was the eagle, symbolising Christ's second coming. Collectively they are known as the Tetramorphs, and their symbolism is centred primarily in the knowledge of astrology, with their most popular visual form surviving into modern times as the ‘World’ card of the Tarot‘s Major Arcana.

Although most Insular art originates from the Irish monastic movement of Celtic Christianity, or La Tène metalwork for the secular elite in the period beginning around 600AD, with the combining of Celtic and Anglo-Saxon styles, many of the patterns used for the Lindisfarne Gospels for example, date back to the pre-christian era, possibly even as far back as Egyptian Coptic Christianity (100AD) and the Druidic tradition (100BC) of the British Isles.

The gospels can be interpreted as an accumulation of cultural symbology that were articulated in a time of great political and religious change within the Euopean Dark Ages.

“Nid dim ond duw, Nid duw ond dim.“ (Nothing without God. Without God, only nothing) - Welsh Druidic proverb.

Historically tracable to the region of Wales in around 200BC, the Druidic order was the primary spiritual practice of the Celtic and Gaulish cultures.

As they had no written records, most of what is gleaned about them by modern historians comes through Roman sources, who may have exaggerated elements of their ritual practices of human sacrifice but definitively praised them for their abilities in mathematics and feats of memory, so much so that their power and respect was recognised as a threat to the Roman empire, and their practices outlawed.

The trinity of Evengelions all feature prominent pre-christian, druidic symbology, such as the Triquerta, Wheel of Taranis, Triskelion and Dara Knot. Druidic symbology (and of other animist traditions) often venerated the architecture of the spiral and the cross to relate instrinsically to the conception of God as the uncreated form of universal energy. The processes of measuring this force arguably gave rise to a number of techniques for organising space, such as time-keeping, making astrological alignments and consturcting monolithic monuments based on the spiralling nature of the moon’s journey through the sky. The conception of God, personified in this very same movement, underlies almost all of the visual vocabulary that anicent cultures used to define the forces which remained hidden behind the physcial world, and is expressed in the druidic proverb “Nid dim ond duw, Nid duw ond dim.“ which has the following translations:

There is nothing Uncreated but that which is hidden.

There is nothing not so concievable but that which is immeasurable.

There is no God but that which is Uncreated.

Only the Uncreated is hidden.

Nothing without God, without God no thing.

Totemic animals and mandalas also feature prominently as a window into a widespread ‘nature-as-divinity complex’ that appeared to permeate the pysche as a fully formed analogue of scientific knowledge, through sacred geometry and in the form of a shamanic lore that was present across the continent, from Asia, the Steppe region and the Middle East, prior to the rise of the Greek and Roman empires. Commonly these cultures, who fell outside of the cultural boundaries of these empires, were collectively known as ‘pagan’ or ‘barbarian’, yet their knowledge of astrology and medicine were complex, omnipresent and esoterically protected through the use of symbology, sometimes, for example, being articulated through forms of art such as tattooing. These aspects gave rise to the archetype of the wizard, or the magician, who’s origins are traced to Persia and the Middle East as the ‘magi’ of pre-Zoroastrian fire cults.

Possibly one of the most recognisable books of the trinity of gospels is the Book of Kells, so named after a town in County Meath, Ireland. However, it is thought that monks who inhabited the now relatively isolated island of Iona were the books’ original artists.

Iona, an island of the Inner Hebrides, Scotland, has an interesting history and expansive mythology that also reaches into pre-history. Thought to be originally named ‘Innis nan Druidhneach’ (The Island of the Druids) in Irish Gaelic, ‘Ì nam ban bòidheach’ (Isle of Beautiful Women) in Scottish Gaelic or ‘Ivova’ (Yew Place) in Latin, it has long been associated as a place of animistic learning for pre-christian, pagan sages.

Columba (or Colmcille, meaning Dove) who was the Irish abbot, evangelist and Christian missionary that played an influential role in the production of the Evangelions, moved to Iona in the early 6th Century and founded its Abbey, which became a central power in the conversion of Britain’s pagan inhabitants to the new religion. Columba’s name was self appointed and means ‘Dove of the Church’ in Latin (his Irish birth name being Crimthann, meaning ‘fox’).

It is interesting to note that the original spelling of the word ‘Iona’ in Hebrew and Greek was Yonah, Jehovah, Yonas or John, which also translates to Dove, a common cross-cultural symbol of peace in relation to a complex of attirbutes normally attributed to ancient goddesses. This suggests that the island of Iona already had a pre-existing cultural symbology before Columba’s arrival, which he probably had prior knowledge of.

Another legend attached to Iona that reinforces the connection between the island’s pre-christian history and its ancient, animistic cultural connections is through the Tuatha Dé Danann, a group of people who were recorded in mythical accounts as being early inhabitants of ancient Ireland and Northern Scotland.

The Tuatha Dé Danann‘s associations with eastern spirituality, matrifocal social structure, veneration of the goddess, proto-indo-european linguistic connections and practice of geomancy are embedded in the cultural artefact known as the Lia Fáil (or the Speaking Stone). This stone was apparently brought to Iona by Columba, who then used it as a travelling altar on his missionary activities to the Scottish mainland.

Before this appropriation, as its name suggests, oral accounts of the Speaking Stone describe it as having properties of resonance and healing.

The island of Iona, as well as having a deep spiritual atmosphere that is still felt to this day by Spiritualists and Neo-pagans travelling from the mainland, exhibits a distinct astmospheric change in its geological nature, due to much of Iona consisting of some of the oldest metamorphic rocks on earth, formed over 2,500 million years ago (source) as well as being located close to an ancient fault line.

One of the most notable psycho-geographical studies of the symbology shows clear connections with early Buddhist iconography, suggesting a vast tapestry of animistic and pagan connections that wove disparate cultural traditions together across the Eurasian continent and even out of North Africa (especially from the Carthaginian colonies of the mediterranean people, commonly known as the Phoenicians or Canaanites, who were a sea-faring culture, arriving in the British Isles to trade for its resources of tin).

These connections, which by no means are accepted by all academics, share mythical origins in an era before written histories gave rise to nation states. However, they are further attested to through the Celtic cultural connections with early Hindu and Buddhist animist beliefs, who’s influence can be mapped symbolically and linguistically all the way from India to Denmark via the comparisons of Cernnunos and Pashupati on the Gundestrup cauldron (dated at 200BC).

Etymologically related to the mythical people of Tuatha Dé Danann of Ireland is the ancient water goddess named Danu, who shares her origns in the Vedic traditions of India (source).

The subsequent occupants of Ireland in the following mythical era, known as the Millesians, also had a druidic tradition that in some aspects mirrored the traditions of the Brahmin priests. The well known cultural figure of Amergin - a Millesian druid and bard, is said to have given Ireland its original name ‘Ériu’, after the daughter of a defeated king of the Tuatha Dé Danann. In his poem, the Song of Amergin (which was said to be able to control the movement of rain clouds) has some stylistic features similarly found in the Indian Vedas.

Interpreting mythology as a force through which emanates a recurring symbology of sacred principles, Art Historian, Jacques Guilmain, suggests that although the classification and categorisation of the geometry and motifs contained within the illuminations is an invaluable approach to understanding their significance, their overall compositional effects, of which the individual motifs are an integral part of the whole, should also be taken into consideration, including emphasis and proportional correlations.

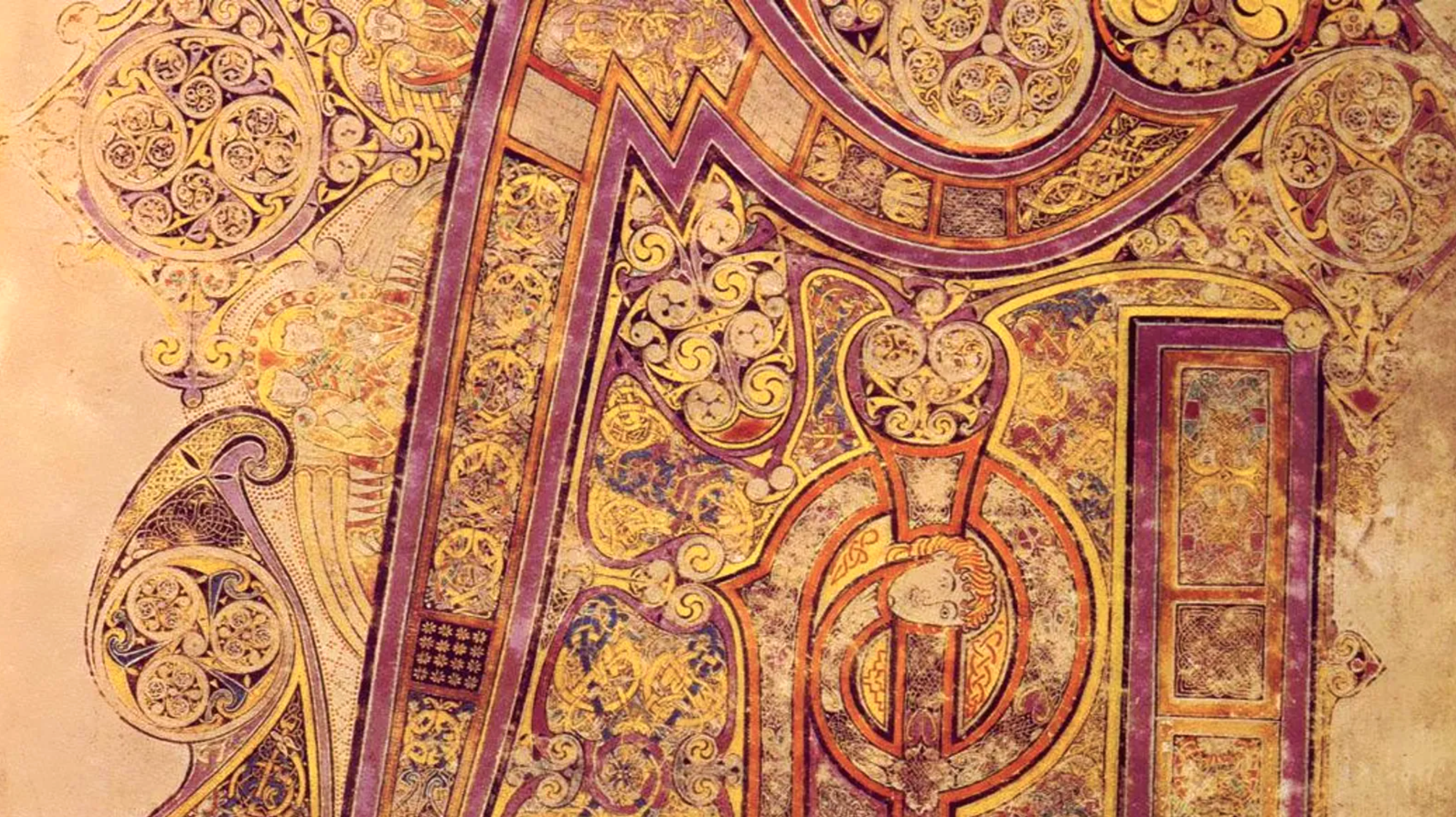

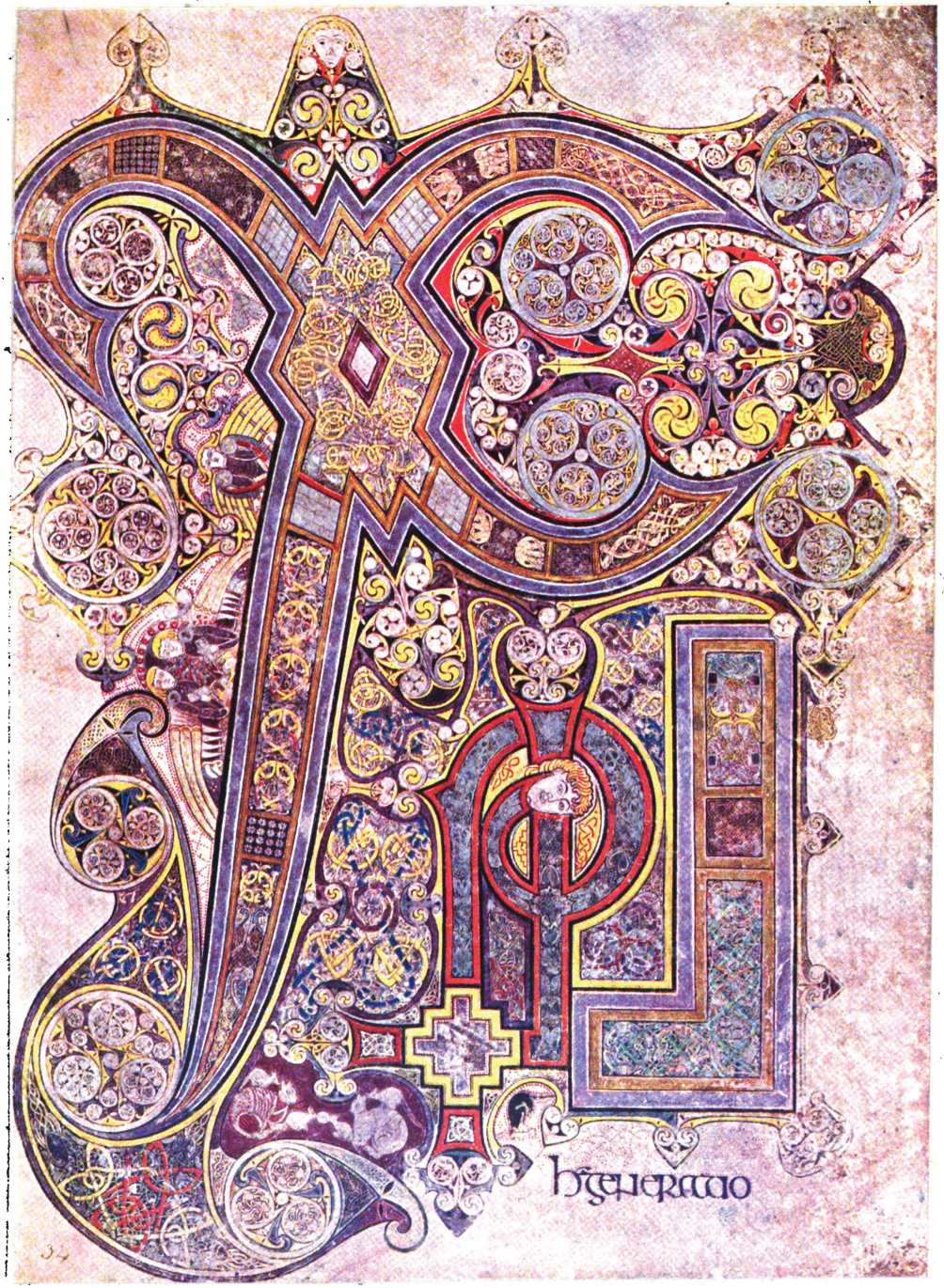

Through the symbolism and architecture of the cross and spiral for example, a meditative space opens into an archetypal realm of animism, overflowing with serpents interlaced with birds and vortices of Fylfots (or Swastikas) and Tibetan-looking Gankyil symbols (often referred to in Western Europe as Triskelions).

Guilmain goes on to write that these motifs “are still evident in the latest date of the three books, the Book of Kells, but they are shrouded in a world of decorative richness, intense technical virtuosity, and ‘baroque’ complexity”, perhaps to place new cultural overlays onto the symbology in an effort to diect their influence in an era of newly defined social and religious paradigms.

Iona, an island of the Inner Hebrides, Scotland, has an interesting history and expansive mythology that also reaches into pre-history. Thought to be originally named ‘Innis nan Druidhneach’ (The Island of the Druids) in Irish Gaelic, ‘Ì nam ban bòidheach’ (Isle of Beautiful Women) in Scottish Gaelic or ‘Ivova’ (Yew Place) in Latin, it has long been associated as a place of animistic learning for pre-christian, pagan sages.

Columba (or Colmcille, meaning Dove) who was the Irish abbot, evangelist and Christian missionary that played an influential role in the production of the Evangelions, moved to Iona in the early 6th Century and founded its Abbey, which became a central power in the conversion of Britain’s pagan inhabitants to the new religion. Columba’s name was self appointed and means ‘Dove of the Church’ in Latin (his Irish birth name being Crimthann, meaning ‘fox’).

It is interesting to note that the original spelling of the word ‘Iona’ in Hebrew and Greek was Yonah, Jehovah, Yonas or John, which also translates to Dove, a common cross-cultural symbol of peace in relation to a complex of attirbutes normally attributed to ancient goddesses. This suggests that the island of Iona already had a pre-existing cultural symbology before Columba’s arrival, which he probably had prior knowledge of.

Another legend attached to Iona that reinforces the connection between the island’s pre-christian history and its ancient, animistic cultural connections is through the Tuatha Dé Danann, a group of people who were recorded in mythical accounts as being early inhabitants of ancient Ireland and Northern Scotland.

The Tuatha Dé Danann‘s associations with eastern spirituality, matrifocal social structure, veneration of the goddess, proto-indo-european linguistic connections and practice of geomancy are embedded in the cultural artefact known as the Lia Fáil (or the Speaking Stone). This stone was apparently brought to Iona by Columba, who then used it as a travelling altar on his missionary activities to the Scottish mainland.

Before this appropriation, as its name suggests, oral accounts of the Speaking Stone describe it as having properties of resonance and healing.

The island of Iona, as well as having a deep spiritual atmosphere that is still felt to this day by Spiritualists and Neo-pagans travelling from the mainland, exhibits a distinct astmospheric change in its geological nature, due to much of Iona consisting of some of the oldest metamorphic rocks on earth, formed over 2,500 million years ago (source) as well as being located close to an ancient fault line.

One of the most notable psycho-geographical studies of the symbology shows clear connections with early Buddhist iconography, suggesting a vast tapestry of animistic and pagan connections that wove disparate cultural traditions together across the Eurasian continent and even out of North Africa (especially from the Carthaginian colonies of the mediterranean people, commonly known as the Phoenicians or Canaanites, who were a sea-faring culture, arriving in the British Isles to trade for its resources of tin).

These connections, which by no means are accepted by all academics, share mythical origins in an era before written histories gave rise to nation states. However, they are further attested to through the Celtic cultural connections with early Hindu and Buddhist animist beliefs, who’s influence can be mapped symbolically and linguistically all the way from India to Denmark via the comparisons of Cernnunos and Pashupati on the Gundestrup cauldron (dated at 200BC).

Etymologically related to the mythical people of Tuatha Dé Danann of Ireland is the ancient water goddess named Danu, who shares her origns in the Vedic traditions of India (source).

The subsequent occupants of Ireland in the following mythical era, known as the Millesians, also had a druidic tradition that in some aspects mirrored the traditions of the Brahmin priests. The well known cultural figure of Amergin - a Millesian druid and bard, is said to have given Ireland its original name ‘Ériu’, after the daughter of a defeated king of the Tuatha Dé Danann. In his poem, the Song of Amergin (which was said to be able to control the movement of rain clouds) has some stylistic features similarly found in the Indian Vedas.

Interpreting mythology as a force through which emanates a recurring symbology of sacred principles, Art Historian, Jacques Guilmain, suggests that although the classification and categorisation of the geometry and motifs contained within the illuminations is an invaluable approach to understanding their significance, their overall compositional effects, of which the individual motifs are an integral part of the whole, should also be taken into consideration, including emphasis and proportional correlations.

Through the symbolism and architecture of the cross and spiral for example, a meditative space opens into an archetypal realm of animism, overflowing with serpents interlaced with birds and vortices of Fylfots (or Swastikas) and Tibetan-looking Gankyil symbols (often referred to in Western Europe as Triskelions).

Guilmain goes on to write that these motifs “are still evident in the latest date of the three books, the Book of Kells, but they are shrouded in a world of decorative richness, intense technical virtuosity, and ‘baroque’ complexity”, perhaps to place new cultural overlays onto the symbology in an effort to diect their influence in an era of newly defined social and religious paradigms.

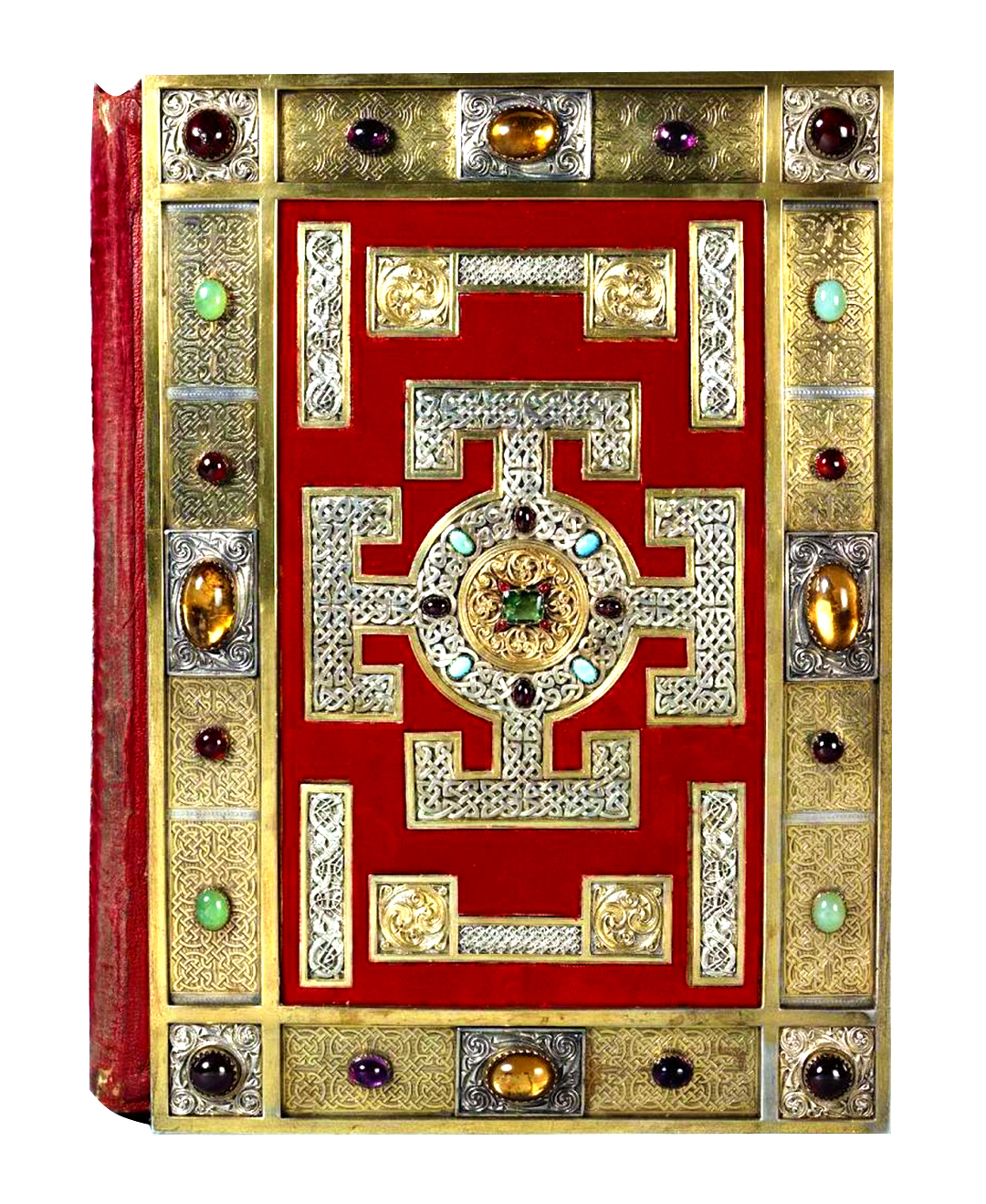

All three Evangelions were considered at somepoint to have been treasure binded - having their covers lavishly decorated with jewells, stones and gold plates. Due to this part of the British Isles being subjected to Viking invasions and political upheaval at the time of the Dark Ages, the original treasure binidngs have since been destroyed or lost. The Lindisfarne Gospels were recreated however, through the literary records that described its original appearance.

The rich decoration of the books are carried out in a wide range of colours drawn from animal, vegetable and mineral sources, some of which were imported over vast distances. Once again, late classical influences from the Mediterranean are blended with Celtic motifs and Germanic animal ornamentation to produce the gospel’s distinctive style. According to studies undertaken by the British Library, “A beaten egg-white preparation called ‘glair’ was used as an adhesive and mixed with pigments. The black ink used for the main text of the gospel is iron gall ink made from oak-galls and iron salts, while a black pigment called lamp black containing particles of carbon was used in the illuminations. Green colours were produced using either verdigris, which is made by suspending copper over vinegar, or vergaut made by mixing blue and yellow pigments.” (source).

The Lindisfarne Gospels are presumed to be the work of a monk named Eadfrith, who became Bishop of Lindisfarne in 698. Eadfrith manufactured ninety of his own colours with "only six local minerals and vegetable extracts". Its also suggested that he "knew about lapis lazuli (a semi-precious stone with a blue tint) from Afghanistan and the Himalayas, but could not get hold of any, and so he made his own" (source).

The copying and decoration of the Lindisfarne Gospels represent a remarkable artistic achievement. The book includes five highly elaborate full-page carpet pages, so-called because of their resemblance to carpets from the eastern Mediterranean.

Either alongside the intricate woven depths of the illuminated manuscripts or twisted inside volutes and tubular typographic forms are animals of everyday life and totemic creatures of another realm who’s spiritual significance was well established in the Middle East and into ancient Europe some one thousand years or more before the Christian era established itself as a dominant socio-political force that changed the character of the psyche.

As Historian of Religion Mircea Eliade described the nature of animistic religions as a kind of pre-conscious connection to nature as a form of divinity, where symbols were ciphers of the potency of unknown forces, stating that “symbols are capable of revealing a modality of the real or a structure of the World that is not evident on the level of immediate experience” (source).

Eliade touches upon the notion of archetypes but also upon a domain of the mind that organises the world as a symbol of a living totality rather than a conceptual, linguistic abstraction that exists in isolation.

The rich decoration of the books are carried out in a wide range of colours drawn from animal, vegetable and mineral sources, some of which were imported over vast distances. Once again, late classical influences from the Mediterranean are blended with Celtic motifs and Germanic animal ornamentation to produce the gospel’s distinctive style. According to studies undertaken by the British Library, “A beaten egg-white preparation called ‘glair’ was used as an adhesive and mixed with pigments. The black ink used for the main text of the gospel is iron gall ink made from oak-galls and iron salts, while a black pigment called lamp black containing particles of carbon was used in the illuminations. Green colours were produced using either verdigris, which is made by suspending copper over vinegar, or vergaut made by mixing blue and yellow pigments.” (source).

The Lindisfarne Gospels are presumed to be the work of a monk named Eadfrith, who became Bishop of Lindisfarne in 698. Eadfrith manufactured ninety of his own colours with "only six local minerals and vegetable extracts". Its also suggested that he "knew about lapis lazuli (a semi-precious stone with a blue tint) from Afghanistan and the Himalayas, but could not get hold of any, and so he made his own" (source).

The copying and decoration of the Lindisfarne Gospels represent a remarkable artistic achievement. The book includes five highly elaborate full-page carpet pages, so-called because of their resemblance to carpets from the eastern Mediterranean.

Either alongside the intricate woven depths of the illuminated manuscripts or twisted inside volutes and tubular typographic forms are animals of everyday life and totemic creatures of another realm who’s spiritual significance was well established in the Middle East and into ancient Europe some one thousand years or more before the Christian era established itself as a dominant socio-political force that changed the character of the psyche.

As Historian of Religion Mircea Eliade described the nature of animistic religions as a kind of pre-conscious connection to nature as a form of divinity, where symbols were ciphers of the potency of unknown forces, stating that “symbols are capable of revealing a modality of the real or a structure of the World that is not evident on the level of immediate experience” (source).

Eliade touches upon the notion of archetypes but also upon a domain of the mind that organises the world as a symbol of a living totality rather than a conceptual, linguistic abstraction that exists in isolation.

“I am a stag: of seven tines,

I am a flood: across a plain,

I am a wind: on a deep lake,

I am a tear: the Sun lets fall,

I am a hawk: above the cliff,

I am a thorn: beneath the nail,

I am a wonder: among flowers,

I am a wizard: who but I

Sets the cool head aflame with smoke?

I am a spear: that roars for blood,

I am a salmon: in a pool,

I am a lure: from paradise,

I am a hill: where poets walk,

I am a boar: ruthless and red,

I am a breaker: threatening doom,

I am a tide: that drags to death,

I am an infant: who but I

Peeps from the unhewn dolmen arch?

I am the womb: of every holt,

I am the blaze: on every hill,

I am the queen: of every hive,

I am the shield: for every head,

I am the tomb: of every hope.”

- ‘Song of Amergin’, translated from the Lebor Gabála Érenn.

I am a flood: across a plain,

I am a wind: on a deep lake,

I am a tear: the Sun lets fall,

I am a hawk: above the cliff,

I am a thorn: beneath the nail,

I am a wonder: among flowers,

I am a wizard: who but I

Sets the cool head aflame with smoke?

I am a spear: that roars for blood,

I am a salmon: in a pool,

I am a lure: from paradise,

I am a hill: where poets walk,

I am a boar: ruthless and red,

I am a breaker: threatening doom,

I am a tide: that drags to death,

I am an infant: who but I

Peeps from the unhewn dolmen arch?

I am the womb: of every holt,

I am the blaze: on every hill,

I am the queen: of every hive,

I am the shield: for every head,

I am the tomb: of every hope.”

- ‘Song of Amergin’, translated from the Lebor Gabála Érenn.

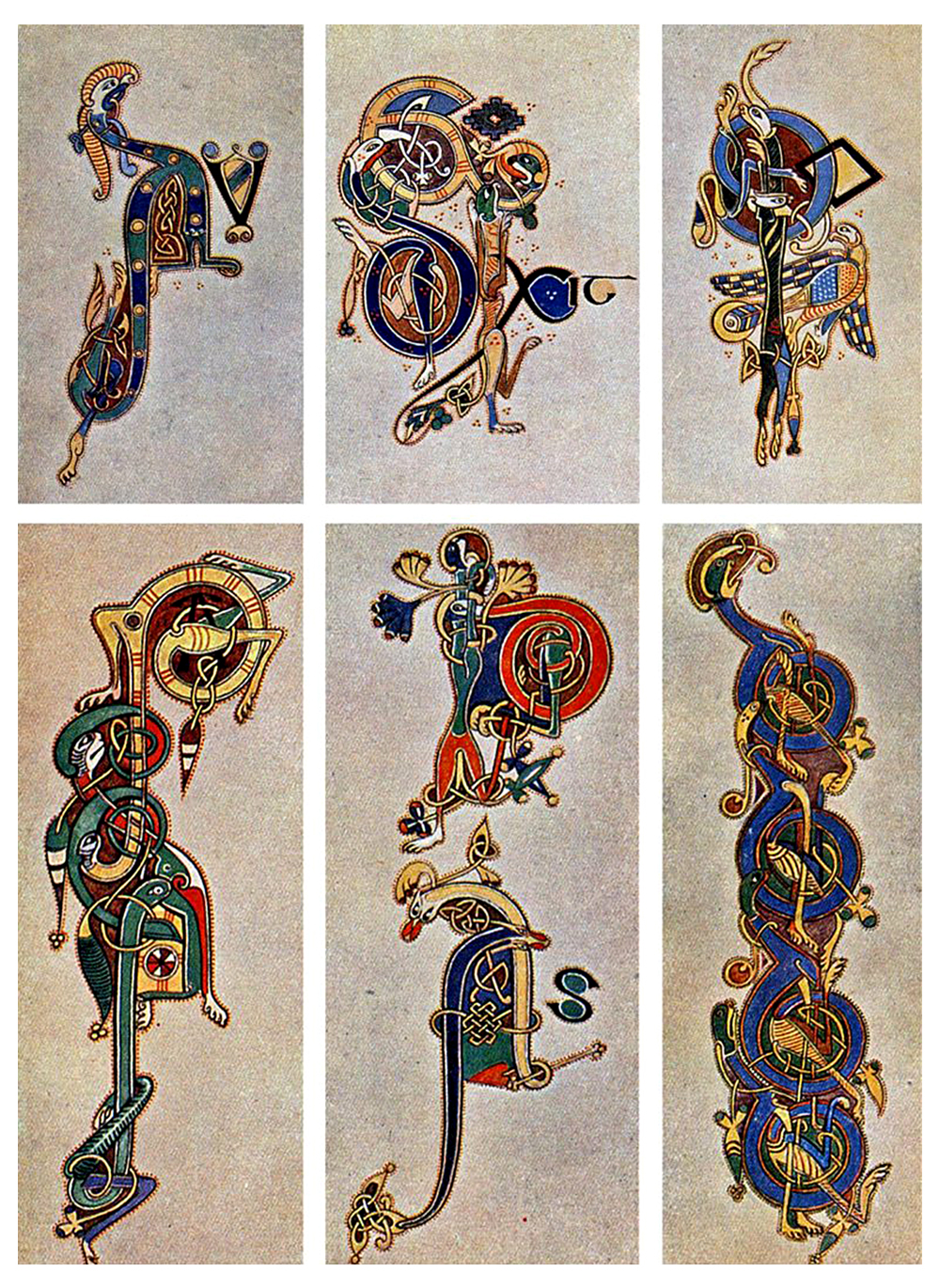

︎Lithograph reproduction by Margaret Stokes, 1861.

︎Animal initials painted by Helen Campbell d’Olier.

The richness of the decoration in the Evangelions, particularly the Book of Kells (800AD), remained relatively unknown until the early decades of the nineteenth century. Reproducing the intricate detail of the artwork posed a considerable challenge, requiring time, patience and a steady hand. Among the earliest artists to undertake the task were two women, Margaret Stokes and Helen Campbell d’Olier.

Margaret Stokes was a highly knowledgeable antiquarian from Dublin, who spent hours poring over the details of the Book of Kells and other Trinity manuscripts which gave her insights that far surpassed those of the academics writing about the art at the time.Helen Campbell d’Olier’s drawings were directly traced from the manuscript, and so the most accurate of the early painted reproductions. She exhibited some of her drawings at the Dublin Exhibition of 1861, and a framed set of her painted animal initials were put on display alongside the manuscript during the early twentieth century (source).

By retracing the line, by following their meanders and their vortices to illuminate the mind and body’s connection to a reality or situation in which human existence is engaged, has always been the necessary existential value of religious symbolism, of which all art, at it’s most subconscious level, is an extension.

As Eliade continues, “Owing to the symbolism of the moon, the World no longer appears as an arbitrary assemblage of heterogeneous and divergent realities. The diverse cosmic levels communicate with each other; they are "bound together" by the same lunar rhythm, just as human life also is "woven together" by the moon and is predestined by the "spinning" goddesses.”

The deeply rooted ancient symbolism of the Evangelions (The Book of Durrow, The Lindisfarne Gospels and The Book of Kells) are yet to reveal all of their wide-reaching cultural secrets beyond their traditional Christian context.

Their visual geometries summon creatures from realms of a forgotten past who possess the rejuvinating qualities of time as a divine substance, uniting cultures within a living image of the sacred. Whilst also retaining their distinct characteristics, they resurrect the original meaning of ‘religion’ as a ‘connection’ or ‘bond’ with the primal movements of nature as a form of identity.

Margaret Stokes was a highly knowledgeable antiquarian from Dublin, who spent hours poring over the details of the Book of Kells and other Trinity manuscripts which gave her insights that far surpassed those of the academics writing about the art at the time.Helen Campbell d’Olier’s drawings were directly traced from the manuscript, and so the most accurate of the early painted reproductions. She exhibited some of her drawings at the Dublin Exhibition of 1861, and a framed set of her painted animal initials were put on display alongside the manuscript during the early twentieth century (source).

By retracing the line, by following their meanders and their vortices to illuminate the mind and body’s connection to a reality or situation in which human existence is engaged, has always been the necessary existential value of religious symbolism, of which all art, at it’s most subconscious level, is an extension.

As Eliade continues, “Owing to the symbolism of the moon, the World no longer appears as an arbitrary assemblage of heterogeneous and divergent realities. The diverse cosmic levels communicate with each other; they are "bound together" by the same lunar rhythm, just as human life also is "woven together" by the moon and is predestined by the "spinning" goddesses.”

The deeply rooted ancient symbolism of the Evangelions (The Book of Durrow, The Lindisfarne Gospels and The Book of Kells) are yet to reveal all of their wide-reaching cultural secrets beyond their traditional Christian context.

Their visual geometries summon creatures from realms of a forgotten past who possess the rejuvinating qualities of time as a divine substance, uniting cultures within a living image of the sacred. Whilst also retaining their distinct characteristics, they resurrect the original meaning of ‘religion’ as a ‘connection’ or ‘bond’ with the primal movements of nature as a form of identity.

Further Reading ︎

Mull and Iona; A Landscape Fashioned by Geology, by David Stephenson.

Iona, Scotland, article, by Philip Carr-Gomm.

Book of Kells, Facimilefinder, article and video.

Sacred-texts, Book of Kells with plate illustrations.

BBC Culture, The Book of Kells, article.

Reproducing the Book of Kells, article.

High North: Cathaginian Exploration of Ireland, article.

List of traditional inks and pigments, artilce.

Digitised Lindisfarne Gospel, British Library, pdf.

Under the Microscope, Lindisfarne Gospel, British Library, article.

Methodological Remarks on the Study of Religious Symbolism, Mercea Eliade, article.

Mull and Iona; A Landscape Fashioned by Geology, by David Stephenson.

Iona, Scotland, article, by Philip Carr-Gomm.

Book of Kells, Facimilefinder, article and video.

Sacred-texts, Book of Kells with plate illustrations.

BBC Culture, The Book of Kells, article.

Reproducing the Book of Kells, article.

High North: Cathaginian Exploration of Ireland, article.

List of traditional inks and pigments, artilce.

Digitised Lindisfarne Gospel, British Library, pdf.

Under the Microscope, Lindisfarne Gospel, British Library, article.

Methodological Remarks on the Study of Religious Symbolism, Mercea Eliade, article.