extreme records

︎Music, Philosophy, Article

︎ Ventral Is Golden

extreme records

︎Music, Philosophy, Article

︎ Ventral Is Golden

︎ Ventral Is Golden

"In passing from history to nature, the myth acts economically: it abolishes the complexity of human acts, it gives them the simplicity of an essence, it organises a world wide open and wallowing in the evident, it establishes a blissful clarity where things appear to mean something by themselves.” - Roland Barthes

Founded by Ülex Xane in Australia in January 1985, Extreme Records began exclusively as a cassette label, releasing music that often defied genres but pulled inspiration from an eclectic mixture of gnostic, esoteric philosophy and the worlds of politics, bio-technology and Dadaism, with titles and tracks ranging from Soma, Stygian Vistas, Merzbow, Antedeluvian, Jiji Muge, Amphibious Premonitions Bureau and Risen from Agartha.

Many of the releases were originally by Australian artists, but later releases saw early experimental electronic artists from around the world grow Extreme into a catalogue of aural tapestries numbering over 60 titles, all notable for their innovative, cross-cultural sensibilities.

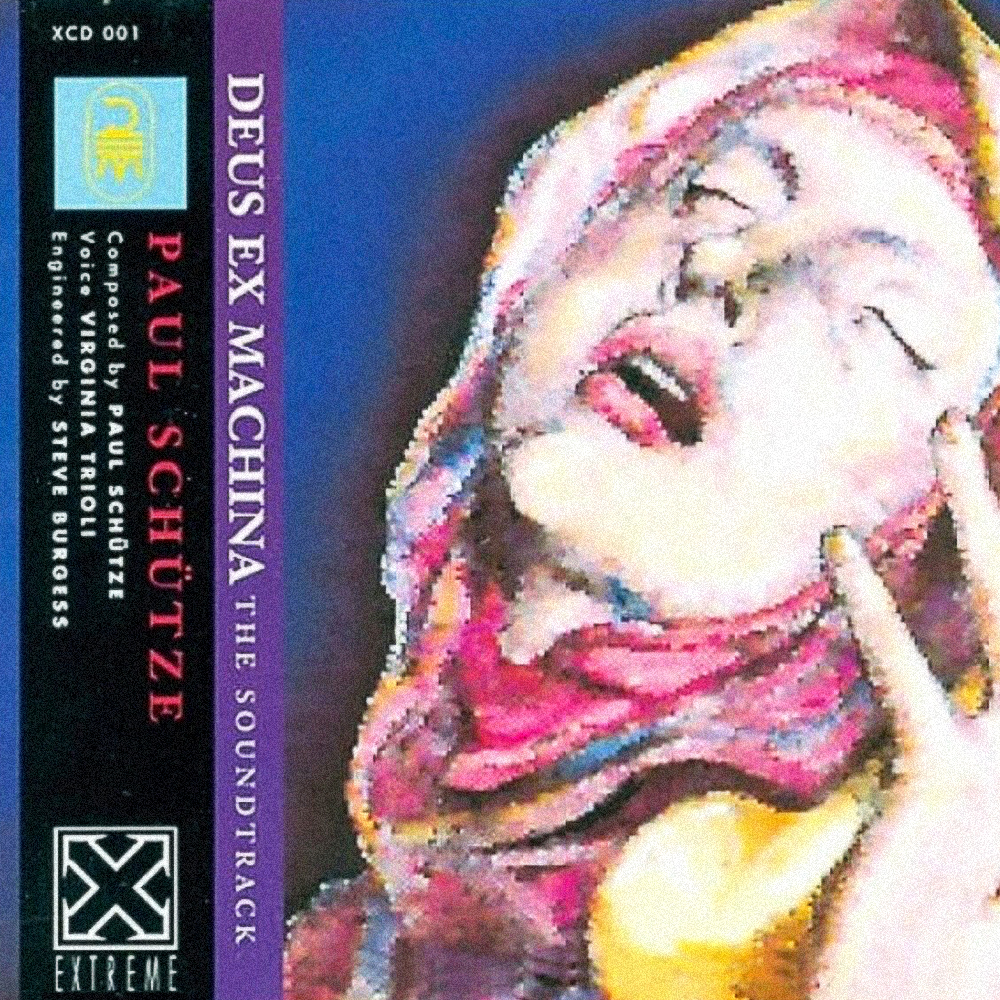

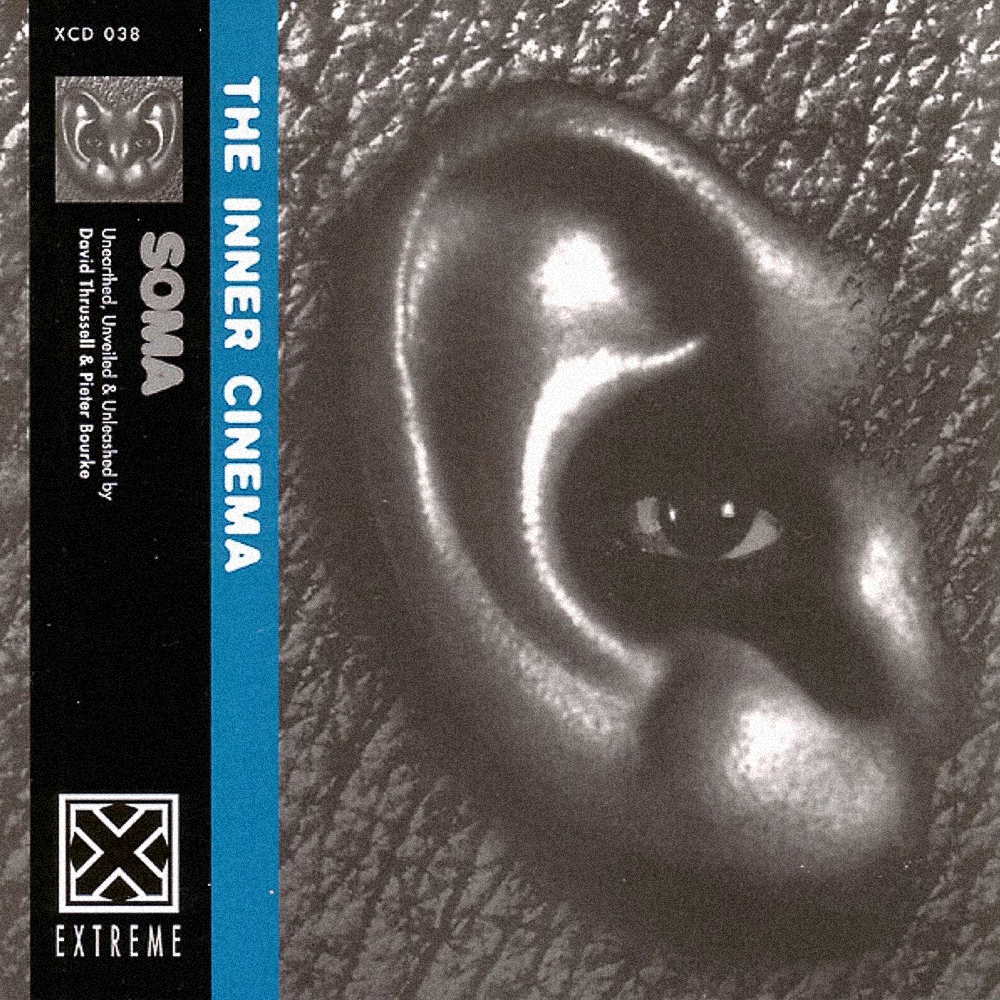

Some of the most successful artists to have worked with Extreme include Japanese noise artist Merzbow, the late Manchester based Muslimgauze (who’s release ‘Intifaxa’ marked the beginning of Extreme Records’ iconic ‘obi strip’ design), Australian based Paul Schütz and Soma, with their interests in ethnomusicology and ambient tribal, to Mo Boma’s electric tribalism and multi-layered future jazz.

Over the course of 1987, Ülex transfered the label to Roger Richards, who continues to run it to this day but as CD release only.

![]()

Many of the releases were originally by Australian artists, but later releases saw early experimental electronic artists from around the world grow Extreme into a catalogue of aural tapestries numbering over 60 titles, all notable for their innovative, cross-cultural sensibilities.

Some of the most successful artists to have worked with Extreme include Japanese noise artist Merzbow, the late Manchester based Muslimgauze (who’s release ‘Intifaxa’ marked the beginning of Extreme Records’ iconic ‘obi strip’ design), Australian based Paul Schütz and Soma, with their interests in ethnomusicology and ambient tribal, to Mo Boma’s electric tribalism and multi-layered future jazz.

Over the course of 1987, Ülex transfered the label to Roger Richards, who continues to run it to this day but as CD release only.

︎Soma - The Inner Cinema, 1996.

︎Soma - Stygian Vistas, 1997.

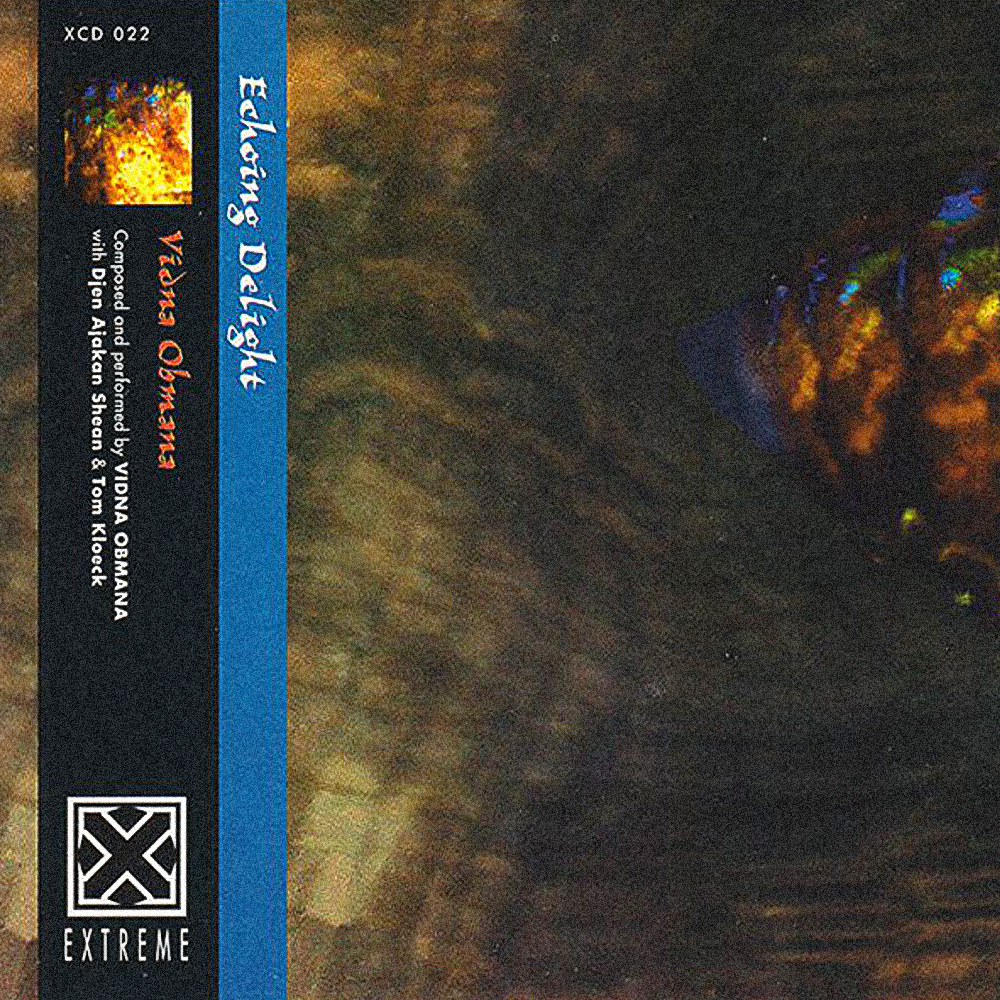

By the early 90's, the distinctive cover layout of the releases had brought the aesthetic of the label into focus, allowing for some very iconic and understated cover art. Around the same time, inventions by engineers such as Ray Kurzweil revolutionised the process of making music and digitising artwork with the invention of the Flatbed Scanner. The availability of transferring music onto Compact Disc made for conditions where pirate radio stations and independent labels could transmit their own audio landscapes. On the surface, this phenomena of democratisation in the digital world had lasting impacts on the way we approach and consume music (and information on a larger scale) as a means of cultural story telling.

Mo Boma (Comprised of Carsten Tiedemann, a native of Germany, and Skuli Sverrisson of Iceland) was a notable example of how ’electric tribalism' seemed to be embedded within the possibilities of story-telling in subcultural art movements of the late 1980’s to mid 90's. Mo Boma's imagery (produced by graphic designer, Silke) complemented their ethereal soundscapes, often confronting western scientism with concepts of biology and eastern spirituality.

In the early to mid 1990's, prior to the widespread, domestic availability of the internet, but within the democratisation of the CD era, saw the ambient tribal trilogy release of 'Myths of The Near Future' from Mo Boma.

With their title inspired by a collection of science fiction stories of the same name, written by J.G Ballard in the 1980’s, alongside their track titles such as ‘Food of the Gods’, ‘Dreaming Weavers’, ’The Kindness of Women’, ‘Garden of Time’, ‘Day of Forever’ and ‘Memories of the Space Age’, their aural trilogy was an extension of the archaic revival, a concept elucidated at the time by philosophers and social scientists like Terence McKenna, Rianne Eisler and Doreen Massey, who were concerned that the utopian image that new technologies offered came at a cost, namely in relation to the inequalities already unconsciously established within industrial societies.

Mo Boma (Comprised of Carsten Tiedemann, a native of Germany, and Skuli Sverrisson of Iceland) was a notable example of how ’electric tribalism' seemed to be embedded within the possibilities of story-telling in subcultural art movements of the late 1980’s to mid 90's. Mo Boma's imagery (produced by graphic designer, Silke) complemented their ethereal soundscapes, often confronting western scientism with concepts of biology and eastern spirituality.

In the early to mid 1990's, prior to the widespread, domestic availability of the internet, but within the democratisation of the CD era, saw the ambient tribal trilogy release of 'Myths of The Near Future' from Mo Boma.

With their title inspired by a collection of science fiction stories of the same name, written by J.G Ballard in the 1980’s, alongside their track titles such as ‘Food of the Gods’, ‘Dreaming Weavers’, ’The Kindness of Women’, ‘Garden of Time’, ‘Day of Forever’ and ‘Memories of the Space Age’, their aural trilogy was an extension of the archaic revival, a concept elucidated at the time by philosophers and social scientists like Terence McKenna, Rianne Eisler and Doreen Massey, who were concerned that the utopian image that new technologies offered came at a cost, namely in relation to the inequalities already unconsciously established within industrial societies.

In the introduction to his book, ‘Myths of the Near Future’ Ballard comments, "I can remember when people throughout the world were intensely interested in the future, and convinced that it would change their lives for the better. In the years after the Second World War, the future was the air that everyone breathed. Looking back, we can see that the blueprint of the world we inhabit today was then being drawn - television and the consumer society, computers, jet travel and the newest wonder drugs transformed our lives and gave us a powerful sense of what the 20th century could do for us once we freed ourselves from war and economic depression. In many ways, we all became Americans."

Ballard had observed that the approach to writing science-fiction itself had gone through changes that were brought about by the limitations of a fractured mythos being fused together under the auspices of a globalised industrial aesthetic, produced in a modern day, media saturated north America mentality. In this new myth of the near future, there was a disconnection from the anceint worlds but at the same time to a desire to leak into them, as a way for the pre-literate hunting psyche to fullfil the needs of a new technological supressor.

Ballard had observed that the approach to writing science-fiction itself had gone through changes that were brought about by the limitations of a fractured mythos being fused together under the auspices of a globalised industrial aesthetic, produced in a modern day, media saturated north America mentality. In this new myth of the near future, there was a disconnection from the anceint worlds but at the same time to a desire to leak into them, as a way for the pre-literate hunting psyche to fullfil the needs of a new technological supressor.

︎Mo Boma - Slolooblade : The Drowned World, 1994.

︎Mo Boma - Loony Toon, 1995.

It's not too difficult to imagine a scenario in the early 1990's, where a blank CD and the internet would have filled an artist with a sense of optimism about the possibilities of a new technological future that was not only affordable but also forced dominant narratives into a specturm of previously unheard voices.

For musicians such as Mo Boma, and the late Muslimgauze (more notably for his music's middle-eastern influence and political commentary), we can begin to see how early experimental musicians were utilising these new avenues of communication to root their cosmic infuences back into an earthly domain.

Oftentimes the complexity of human acts are reduced to 'simple essences’ of mythology for the sake of the dominant channels of mainstream media to use them as convenient symbols to reassure political stability - a new vision of aquiring a singular, teritorial mass for the massless media map to wrap itself around. In our own time, technology has produced an excess of clarity and something of a recapitulation of these old ideals.They are simultaneously experienced through object fetishism of culture, identity and consumer technology that essentially throws humanity outside of time itself.

For musicians such as Mo Boma, and the late Muslimgauze (more notably for his music's middle-eastern influence and political commentary), we can begin to see how early experimental musicians were utilising these new avenues of communication to root their cosmic infuences back into an earthly domain.

Oftentimes the complexity of human acts are reduced to 'simple essences’ of mythology for the sake of the dominant channels of mainstream media to use them as convenient symbols to reassure political stability - a new vision of aquiring a singular, teritorial mass for the massless media map to wrap itself around. In our own time, technology has produced an excess of clarity and something of a recapitulation of these old ideals.They are simultaneously experienced through object fetishism of culture, identity and consumer technology that essentially throws humanity outside of time itself.

︎Mo Boma - Dreaming Weavers, 1996.

Social Scientist Doreen Massey put it that "because our world is "speeding up" and "spreading out", time-space compression is more prevalent than ever as internationalisation takes place. Cultures and communities are merged during time-space compression due to rapid growth and change, as "layers upon layers" of histories fuse together to shift our ideas of what the identity of a 'place' should be."

What Massey could have been alluding to are the following questions:

How can we maintain identity if there are no boundaries, no fixity, no difference?

How can we hold onto the rootedness of ‘place’ without being defensive and reactionary in the midst of a reactionary and defensive society?

Collective consciousness of the media indoctrinated classes has become something of a drained swimming pool, haunted by the presence of it's own echo - a place Ballard would have called 'psychic-zero'. His metaphor of the swimming pool to explore psychic space is both modern in its image and stagnant in its actuality. It calls up neological expressions like ‘surfing the web’, once used to broaden personal understanding through consuming bits of info-flotsam, which has since eroded over time into a kind of relic of linguistics. Perhaps the more appropriate analogy could be ‘streaming’, leading to a more ecologically oriented ‘cleansing of the ocean of cyber space’, the inevitable place where all streams lead.

In his Mythologies book, Roland Barthes said “there is only one means to exorcise the possessive nature of the man on a ship; it is to eliminate the man and to leave the ship on its own. The ship then is no longer a box, a habitat, an object that is owned; it becomes a travelling eye, which comes close to the infinite; constantly breeding departures.”

What Massey could have been alluding to are the following questions:

How can we maintain identity if there are no boundaries, no fixity, no difference?

How can we hold onto the rootedness of ‘place’ without being defensive and reactionary in the midst of a reactionary and defensive society?

Collective consciousness of the media indoctrinated classes has become something of a drained swimming pool, haunted by the presence of it's own echo - a place Ballard would have called 'psychic-zero'. His metaphor of the swimming pool to explore psychic space is both modern in its image and stagnant in its actuality. It calls up neological expressions like ‘surfing the web’, once used to broaden personal understanding through consuming bits of info-flotsam, which has since eroded over time into a kind of relic of linguistics. Perhaps the more appropriate analogy could be ‘streaming’, leading to a more ecologically oriented ‘cleansing of the ocean of cyber space’, the inevitable place where all streams lead.

In his Mythologies book, Roland Barthes said “there is only one means to exorcise the possessive nature of the man on a ship; it is to eliminate the man and to leave the ship on its own. The ship then is no longer a box, a habitat, an object that is owned; it becomes a travelling eye, which comes close to the infinite; constantly breeding departures.”

The avenues of information that were available in the early nineties, and the psychological processes that had to be used in order to breakdown that information and assimilate it into everyday life would have been slightly different to our own electric habitudes since technology’s rapid accelerationism.

Our subject matter, like our natures, are altered by the means through which we approach them, and when the internet hovered above the horizon like a benevolent spaceship that promised to resuscitate the drowned world, these ideas may have seemed more like the re-dawning of a Golden Age. Maybe the resuscitation already happened, maybe it didn’t, but what I think digital culture and rare electronic music has given us in one sense, is the seed of an eternal optimism nested inside the concept of an eternal return that is embedded within cyber space, and a constant reminder to never mistake that space for absolute reality.

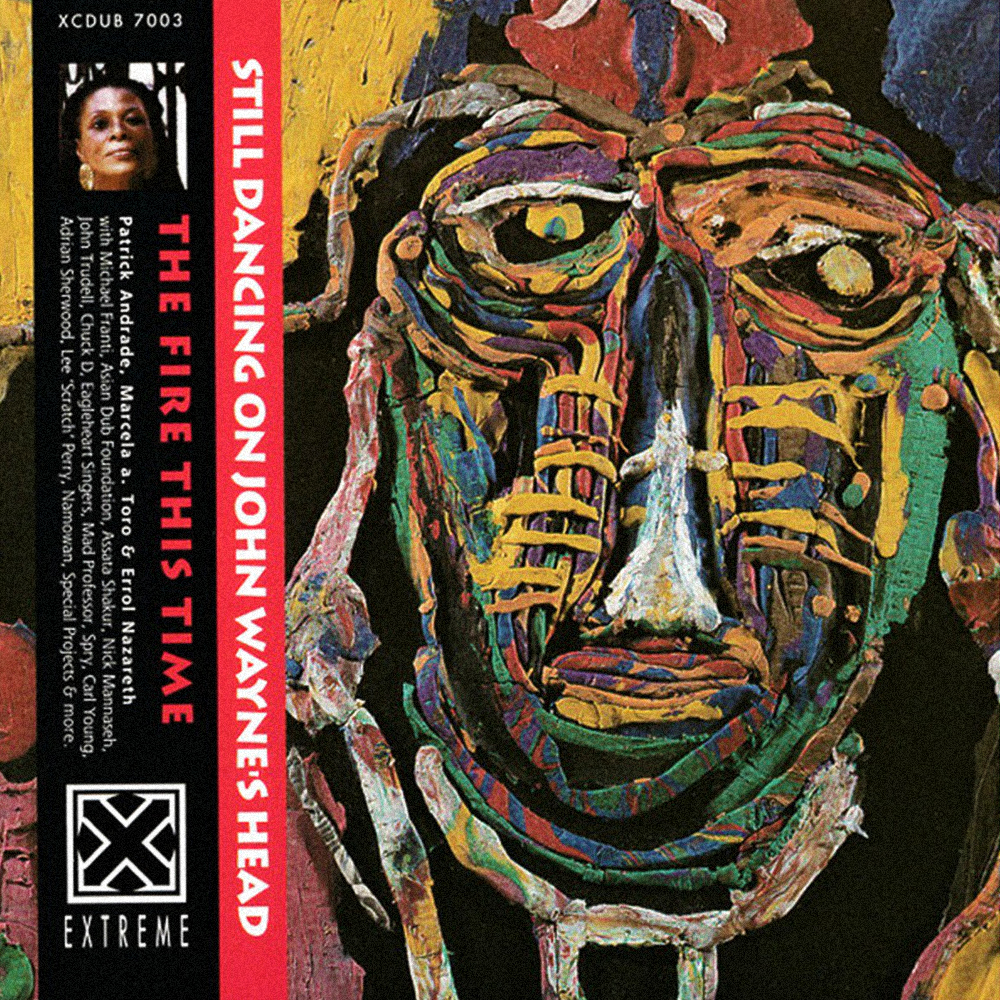

︎The Fire This Time - Oka, 1998.

︎Muslimgause - Fakir, 1992.

Further Reading ︎

Daily Art Magazine, articl

Face to Face, J.G Ballard interview, video

A Global Sense of Place, Doreen Massey, article Mythologies, Roland Barthes, book

Extreme Records, Discogs