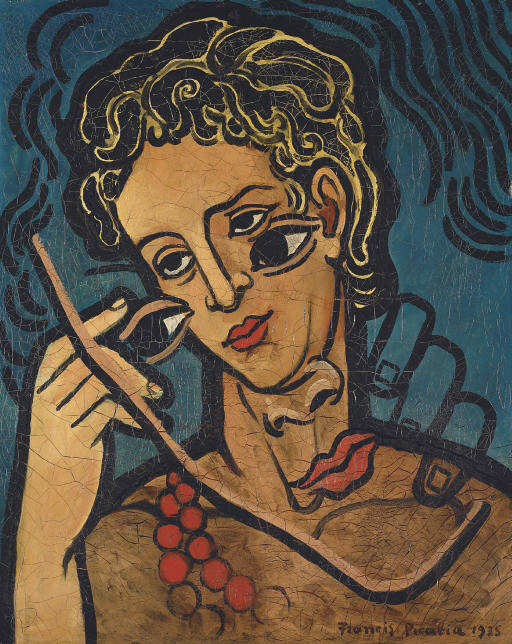

francis picabia

︎Artist, Painting, Dada, Philosophy

︎ Ventral Is Golden

francis picabia

︎Artist, Painting, Dada, Philosophy

︎ Ventral Is Golden

︎ Ventral Is Golden

“Knowledge is ancient error reflecting on its youth.“

Francis Picabia once said that “all the painters who appear in our museums are failures at painting; the only people ever talked about are failures; the world is divided into two categories of people: failures and those unknown.”

He was a French avant-garde painter, typographist, poet and above all a provocateur.

Being one of the major precursors to the Dada movement in the United States and in France, Picabia was already predisposed to holding contradictory positions within the art establishments.

From an early age he had a natural flare for painting, often painting forgeries pieces in his father’s art collection to sell the originals to finance his stamp collection.

In later life he would express work in almost every contemporaneous art style but eventually turn his back on the Dadaists, the Surrealists that once apodted him, who’s politics were moulded by, what he beleived to be a 1920's bourgeoise vision of modernity. He declared, in his Cannibal Dadaist Manifesto, that “Dada is like your hopes: nothing, like your paradise: nothing, like your idols: nothing, like your heroes: nothing, like your artists: nothing, like your religions: nothing."

The kind of nihilism that characterised both Picabia's relationship with the Dadaists and Surrealists, and the mechanical age in general, would lead towards Picabia's more deconstructionist views. This nihilism, nevertheless, contained seeds of optimism that rooted itself in the anxiety of the emerging social structures. Through these structures, such epigenetic phenomena as art, science and philosophy (elevated by the earlier Romantics) played even more of a substantial role in the struggle to inter-contextualise a collective, emotional religiosity into an individualised, automated post-modern era.

He was a French avant-garde painter, typographist, poet and above all a provocateur.

Being one of the major precursors to the Dada movement in the United States and in France, Picabia was already predisposed to holding contradictory positions within the art establishments.

From an early age he had a natural flare for painting, often painting forgeries pieces in his father’s art collection to sell the originals to finance his stamp collection.

In later life he would express work in almost every contemporaneous art style but eventually turn his back on the Dadaists, the Surrealists that once apodted him, who’s politics were moulded by, what he beleived to be a 1920's bourgeoise vision of modernity. He declared, in his Cannibal Dadaist Manifesto, that “Dada is like your hopes: nothing, like your paradise: nothing, like your idols: nothing, like your heroes: nothing, like your artists: nothing, like your religions: nothing."

The kind of nihilism that characterised both Picabia's relationship with the Dadaists and Surrealists, and the mechanical age in general, would lead towards Picabia's more deconstructionist views. This nihilism, nevertheless, contained seeds of optimism that rooted itself in the anxiety of the emerging social structures. Through these structures, such epigenetic phenomena as art, science and philosophy (elevated by the earlier Romantics) played even more of a substantial role in the struggle to inter-contextualise a collective, emotional religiosity into an individualised, automated post-modern era.

Picabia’s provocations were a poetic prying into this new industrial reality to discover where new contradictions and emotions could exist within a mechanised framework. It was a quest for the convulsions of consciousness within a newly dehumanised worldview, but also a world that now presented an opportunity to transcend the human condition and previously held social values that for Picabia were too restrictive.

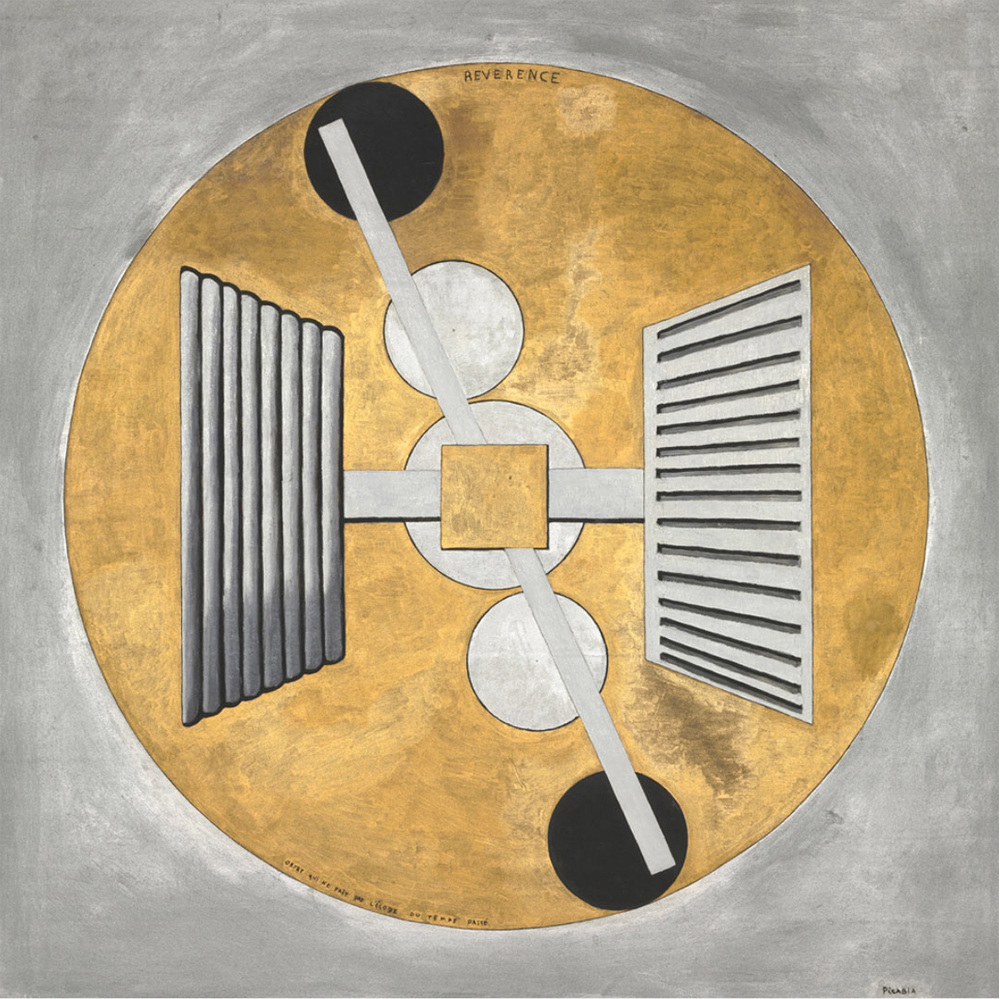

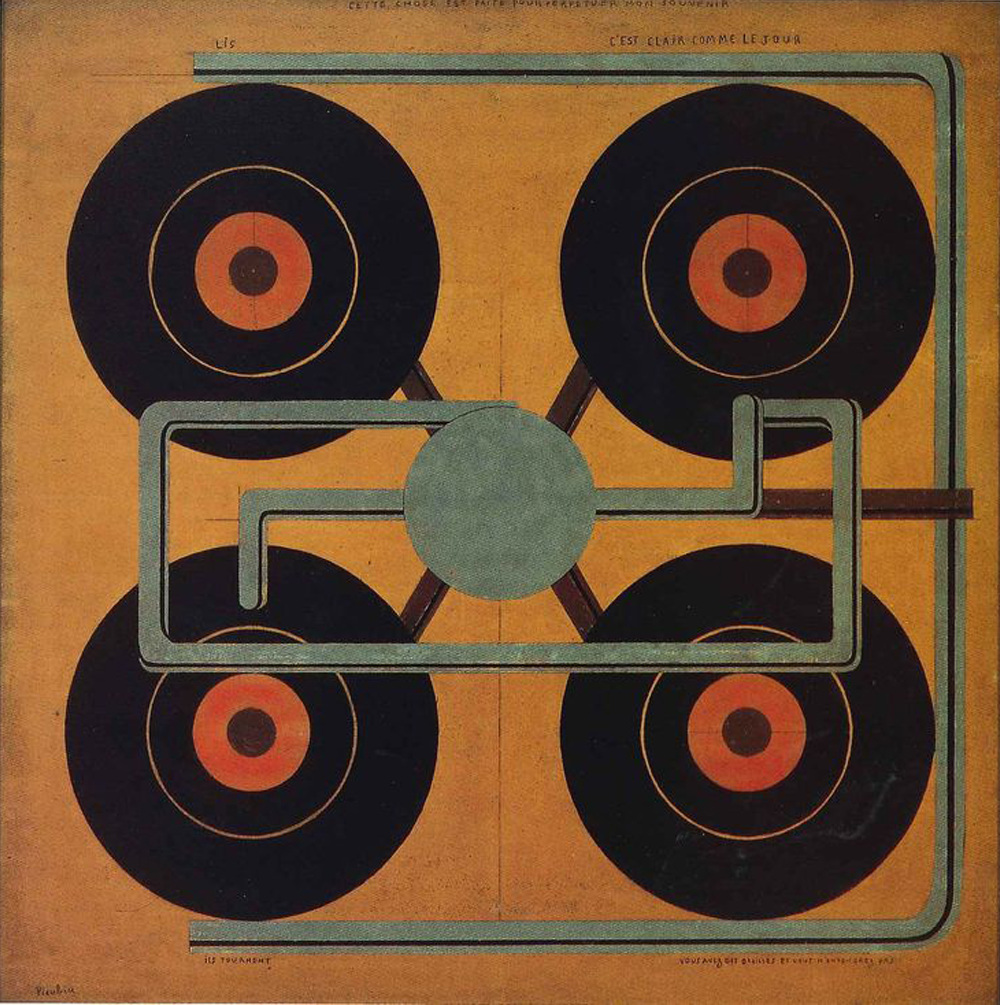

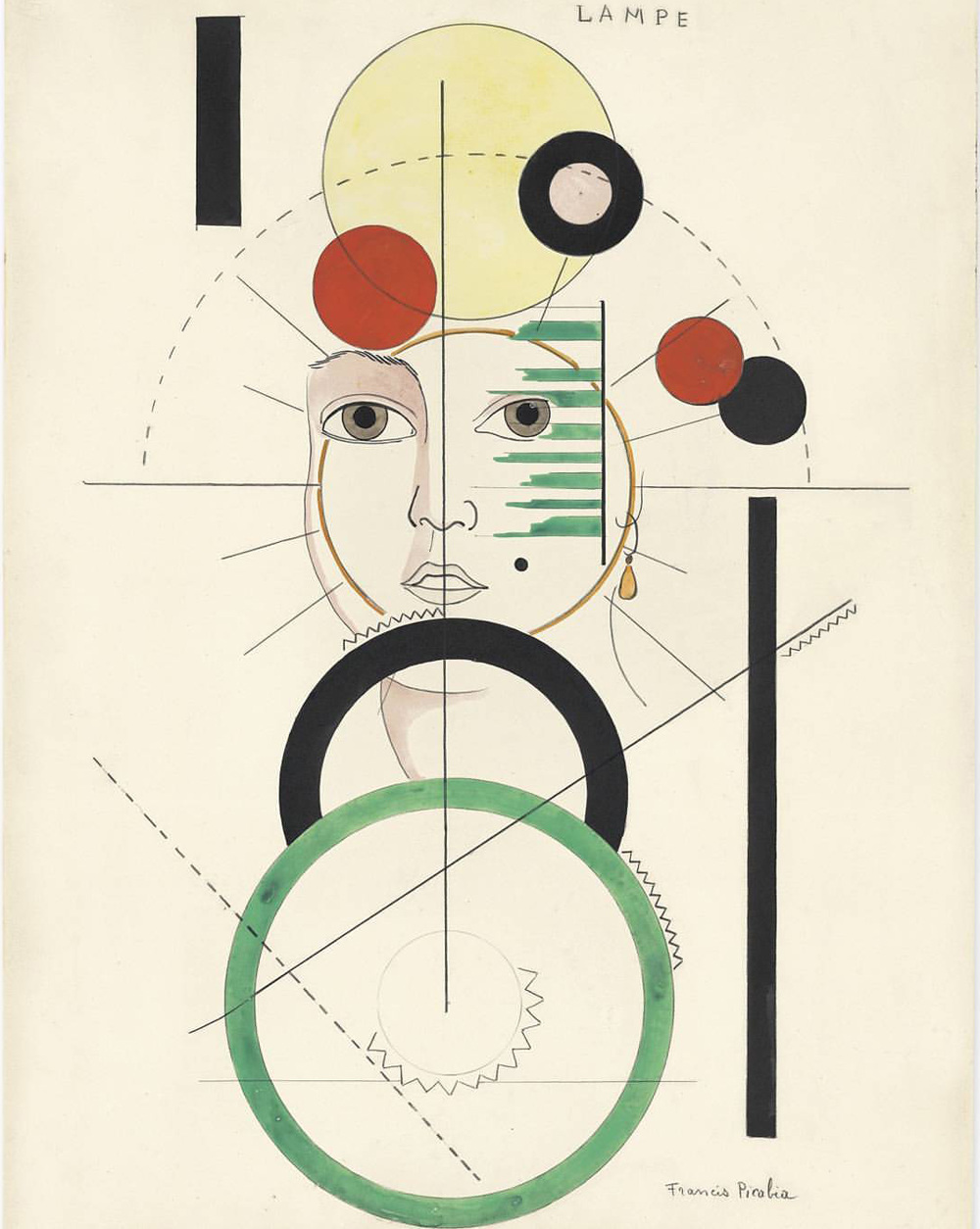

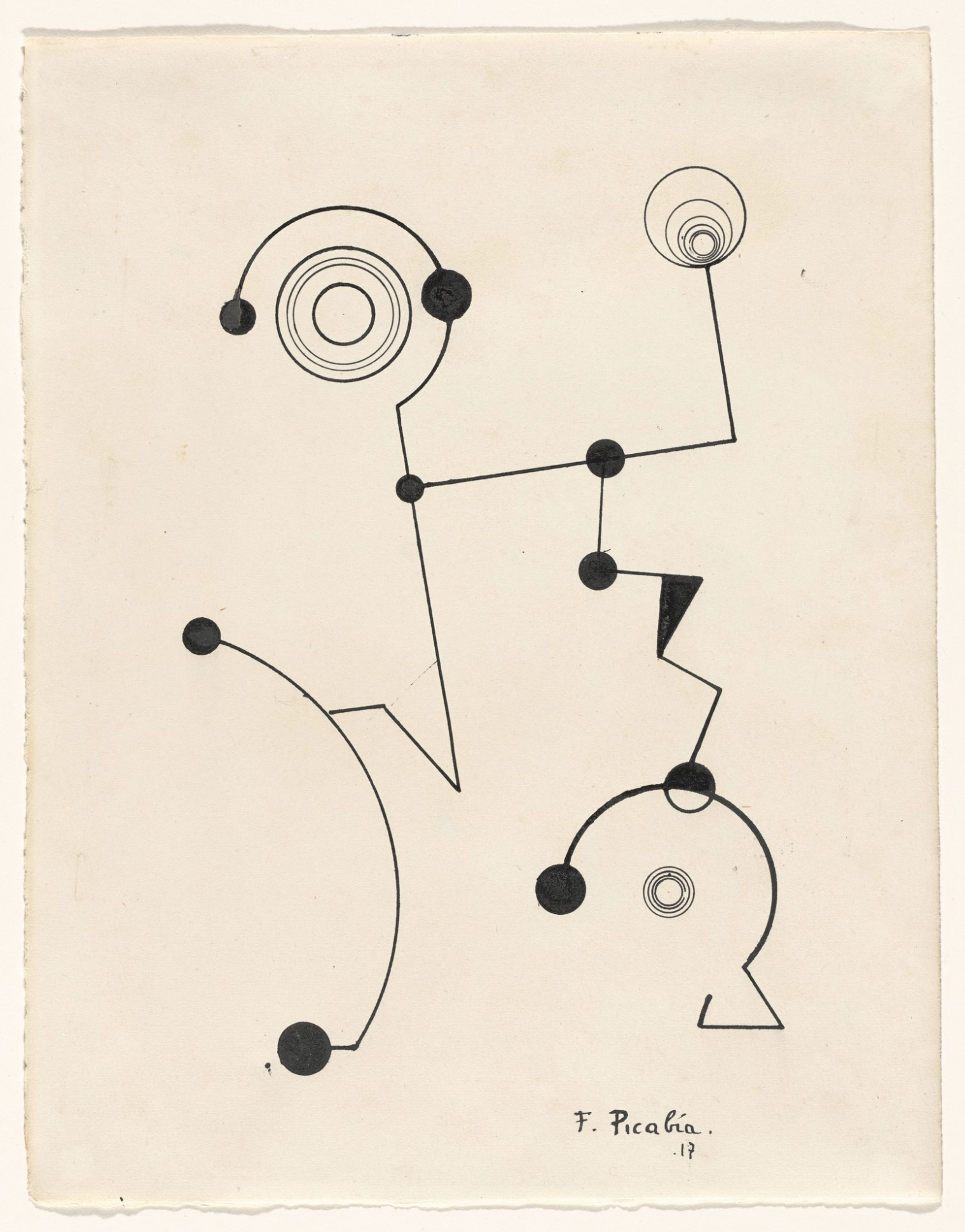

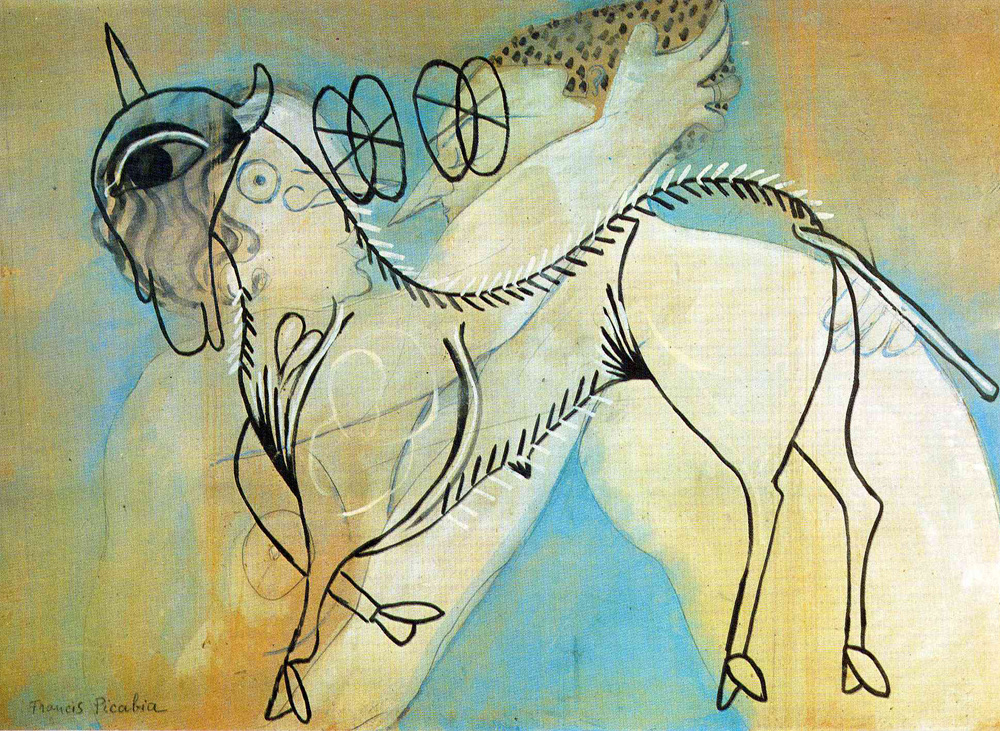

In his ‘Mechanomorphic’ series, Picabia would explore the parodies of machine parts within portraiture, owing to his views that humans were machines not ruled by their rational minds but by their compulsive hungers.

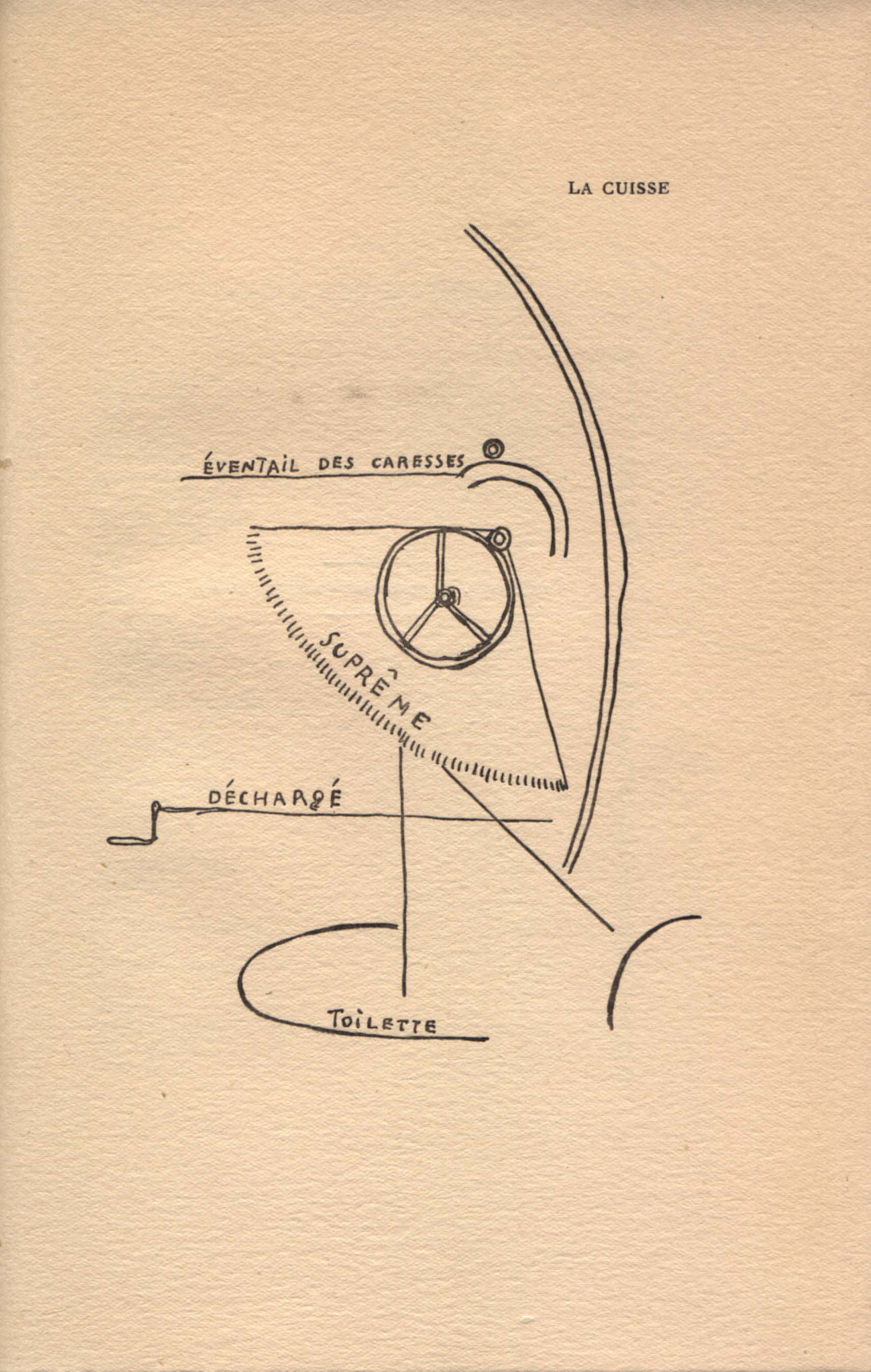

To imbue the institutions with the kinds of feelings Picabia thought they lacked required a counter-intuitive perspective, one that elevated the natural world of emotion in the revolutions of a mechanised mass produced vision of environment. The lyrical style of his visual poem assemblages (often punctuated sketches of words, gears and levers) equated to seduction and copulation with the manufacturing process itself.

In his ‘Mechanomorphic’ series, Picabia would explore the parodies of machine parts within portraiture, owing to his views that humans were machines not ruled by their rational minds but by their compulsive hungers.

To imbue the institutions with the kinds of feelings Picabia thought they lacked required a counter-intuitive perspective, one that elevated the natural world of emotion in the revolutions of a mechanised mass produced vision of environment. The lyrical style of his visual poem assemblages (often punctuated sketches of words, gears and levers) equated to seduction and copulation with the manufacturing process itself.

Picabia moved to Spain during World War I and began publishing the longest running magazine related to Dada and Surrealism, entitled 391.

The publication would act primarily as a literary outlet for himself and other poets who had found refuge in the neutrality of Spain, and who wanted to revolt against the conventions of the wider European culture.

By the time the final issue of 391 was published, Picabia had turned his back once again on the self-proclaimed authorities of Surrealism, and began producing 'original forgeries' of acclaimed anti-art pieces instead. Some belonging to the likes of Marcel Duchamp, which contributed to what became Picabia’s more derrisive and militarian tone.

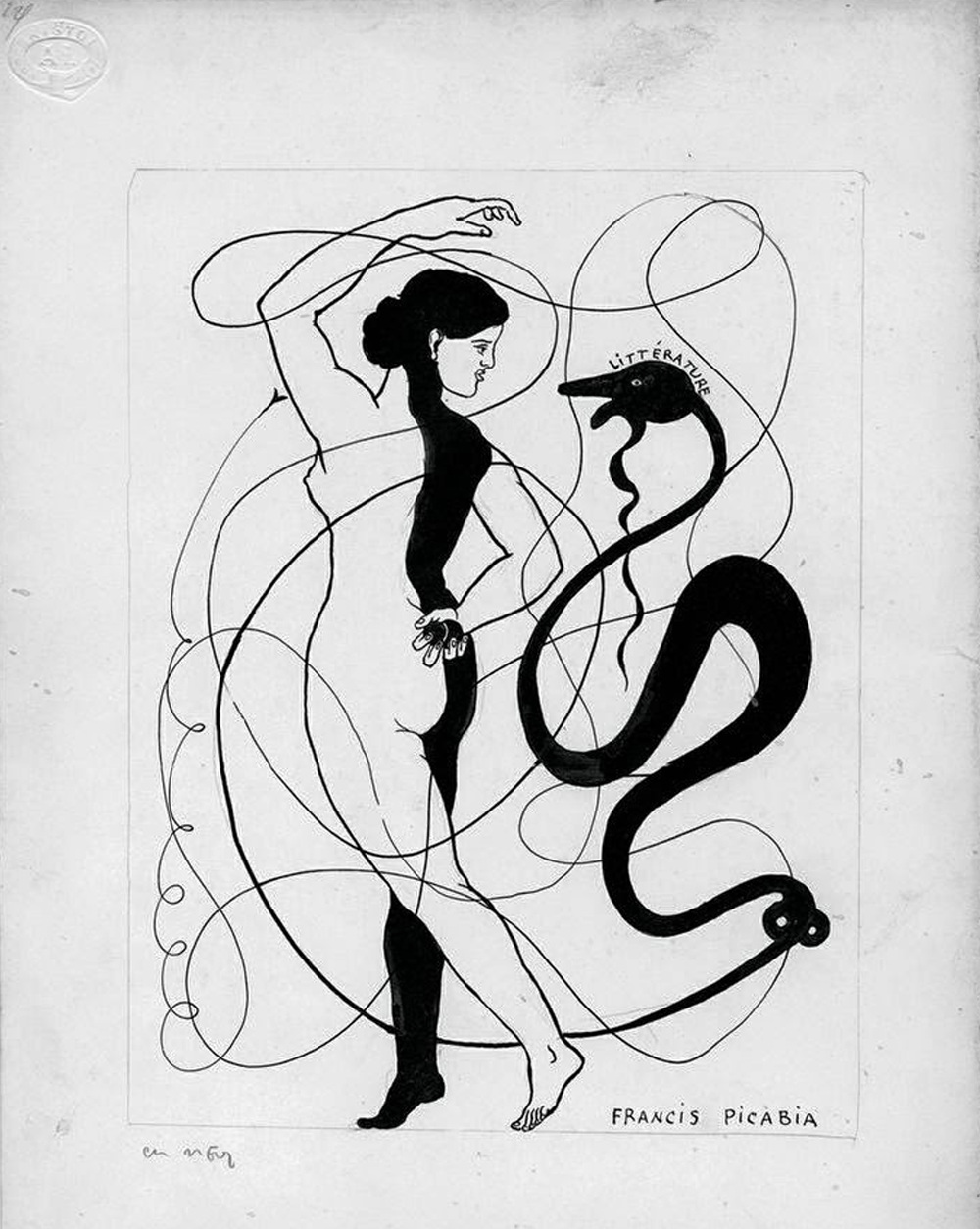

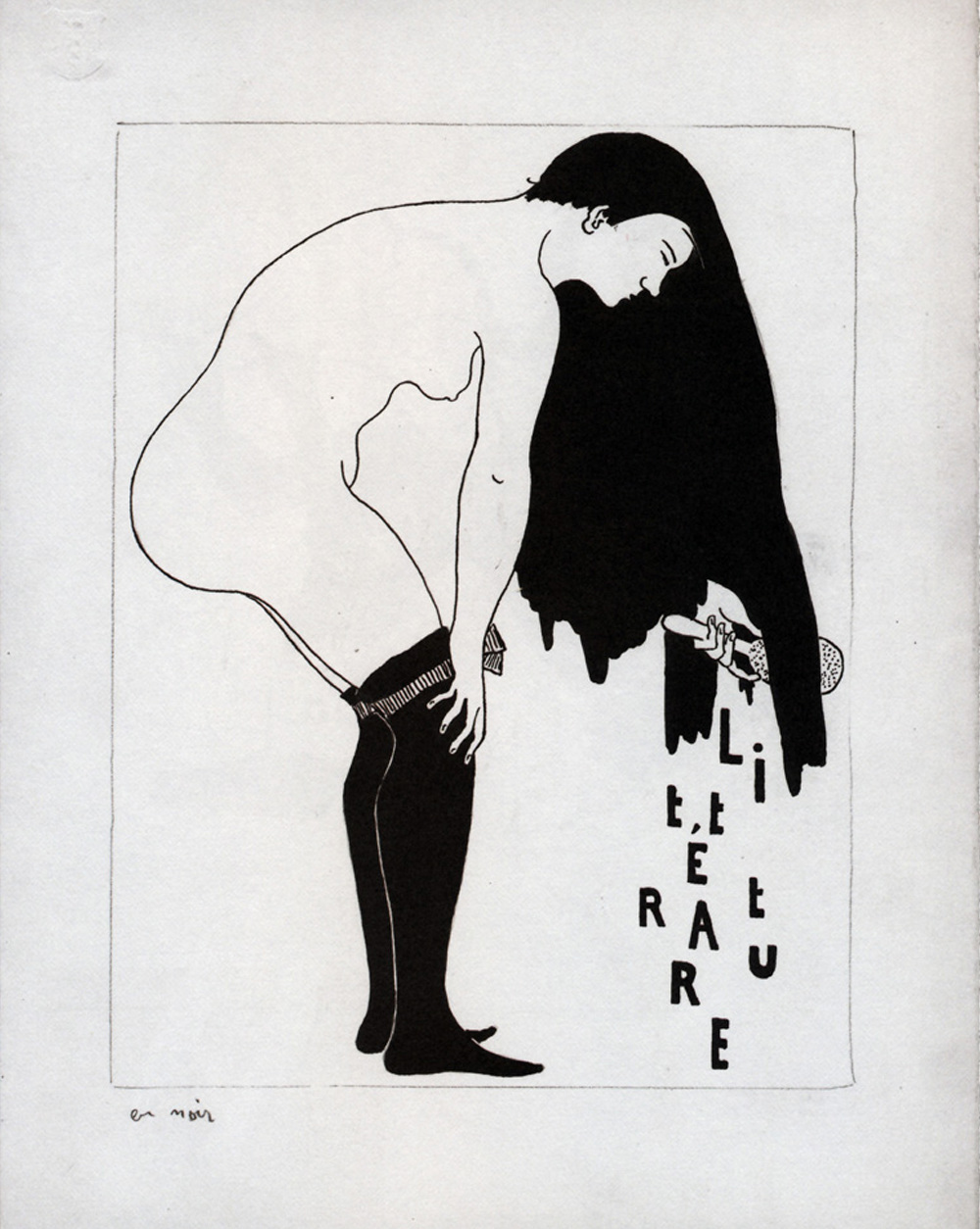

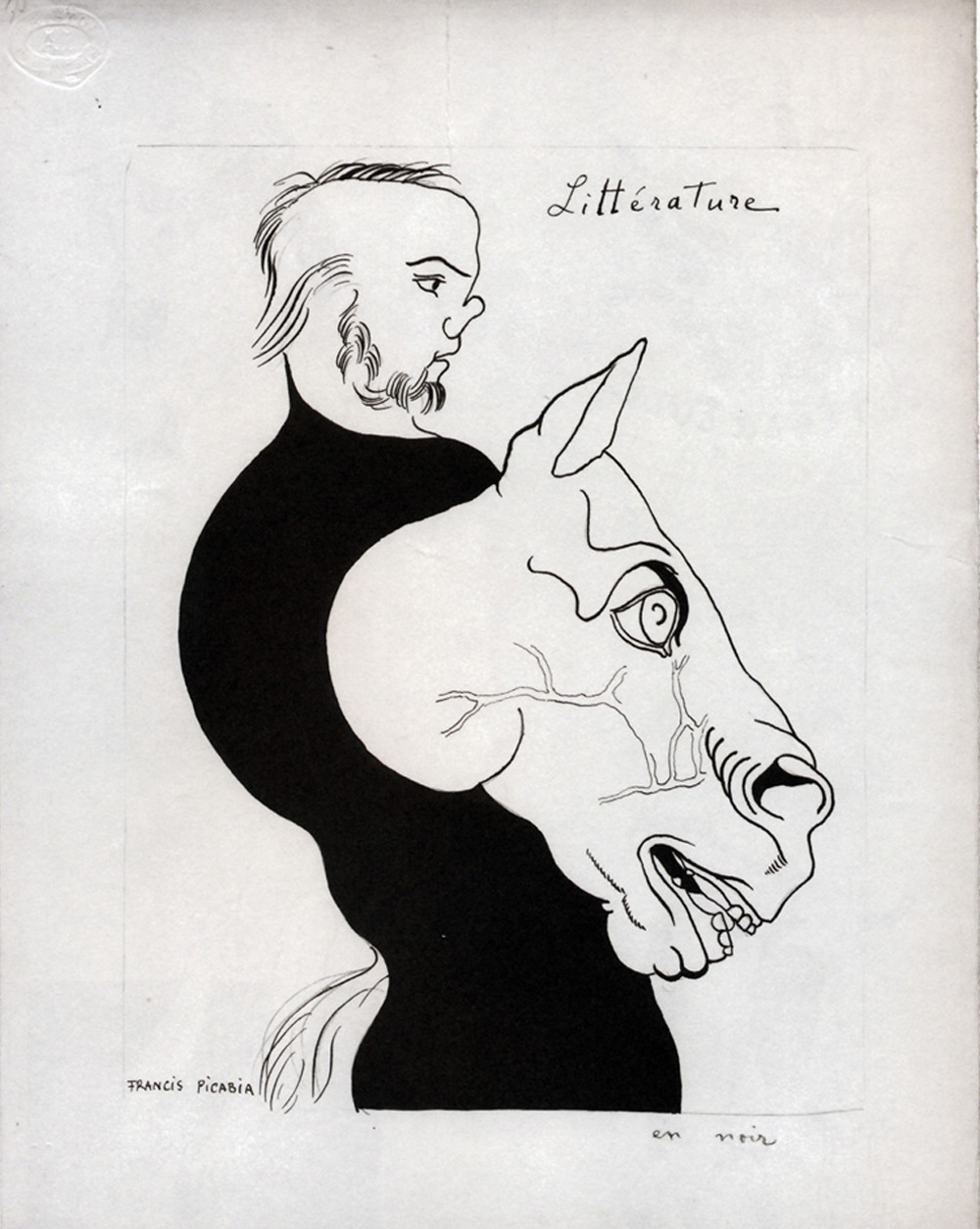

A couple of years after the first issue of 319, ‘Littérature’, a publication founded by André Breton, Philippe Soupault, and Louis Aragon, was one of the first Surrealist publications that found a space in which it could haunt the corridors of academic thought, specifically by critiquing the parameters that initially allowed it to come into existence.

In 1922, Picabia was commissioned by Breton to illustrate the front covers in a series of black & white illustrations. In a letter from Marcel Duchamp to Breton in 1922, Duchamp wrote that the scandalous nature of Picabia’s images, many of which blended sexual and religious symbolism, made it difficult for Duchamp to distribute the publication in New York, much to his delight.

After his disavowal of Dadaism and Surrealism, and when the absurd limitations of 391 had been realised, Picabia had one more seed of optimism tucked in his nihilism. As a way for Picabia to articulate the implicit sense of dehumanisation within the mechanised, industrial society, he created a new movement called ‘Instantanéisme’, where he claimed that the only worthwhile art movement was ‘perpetual motion’. It was a kind of self-deprication echoed in a sentiment by Groucho Marx's, "I don't care to belong to any club that will have me as a member".

In the ultimate issue of 391, Picabia included a list of Instantanéisme's most 'exceptional men'. Of course this issue was never published, thus suspending, at least in the eyes of Picabia, the recapitulation of predominantly white, western patriarchal gatekeepers into the academic art world of his time.

The publication would act primarily as a literary outlet for himself and other poets who had found refuge in the neutrality of Spain, and who wanted to revolt against the conventions of the wider European culture.

By the time the final issue of 391 was published, Picabia had turned his back once again on the self-proclaimed authorities of Surrealism, and began producing 'original forgeries' of acclaimed anti-art pieces instead. Some belonging to the likes of Marcel Duchamp, which contributed to what became Picabia’s more derrisive and militarian tone.

A couple of years after the first issue of 319, ‘Littérature’, a publication founded by André Breton, Philippe Soupault, and Louis Aragon, was one of the first Surrealist publications that found a space in which it could haunt the corridors of academic thought, specifically by critiquing the parameters that initially allowed it to come into existence.

In 1922, Picabia was commissioned by Breton to illustrate the front covers in a series of black & white illustrations. In a letter from Marcel Duchamp to Breton in 1922, Duchamp wrote that the scandalous nature of Picabia’s images, many of which blended sexual and religious symbolism, made it difficult for Duchamp to distribute the publication in New York, much to his delight.

“Everything in the world

far from the truth

is like a hurricane of divine roads

like the light of heaven.

Those women who deny hereafter

have a place next to me.

I am the virtuous guide

in the crystal city.“ - Francis Picabia.

After his disavowal of Dadaism and Surrealism, and when the absurd limitations of 391 had been realised, Picabia had one more seed of optimism tucked in his nihilism. As a way for Picabia to articulate the implicit sense of dehumanisation within the mechanised, industrial society, he created a new movement called ‘Instantanéisme’, where he claimed that the only worthwhile art movement was ‘perpetual motion’. It was a kind of self-deprication echoed in a sentiment by Groucho Marx's, "I don't care to belong to any club that will have me as a member".

In the ultimate issue of 391, Picabia included a list of Instantanéisme's most 'exceptional men'. Of course this issue was never published, thus suspending, at least in the eyes of Picabia, the recapitulation of predominantly white, western patriarchal gatekeepers into the academic art world of his time.

In the cultural context of the 1920’s, the effects of mechanisation alongside a growing interest in the west towards eastern spirituality, saw a desire to craft an anthropocentric view to distinguish a relationship between human and machine, or rather the preservation of spirit within machine, since modernity created a spiritual void where the church once stood.

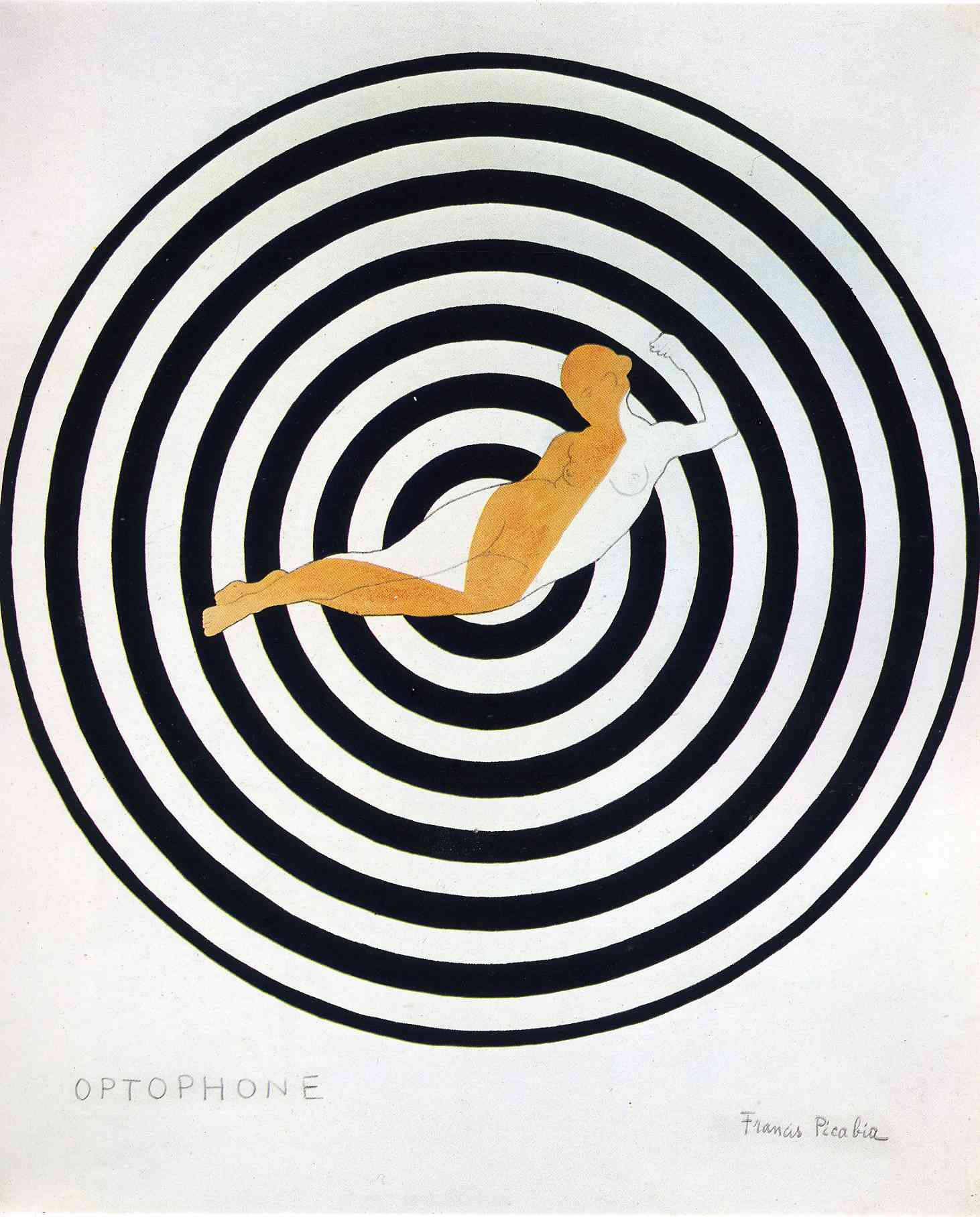

In his lifetime, Picabia believed that painting had begun its inexorable decline into endless self reflective mass production. Cinematic technologies offered a greater power than print to disrupt the expectations of the audience and to undermine the norms and codes of social conventions. He transferred his 'esprit dada' into a new phase of artistic production which involved - and fetishised more than ever before - the spirit of the machine.

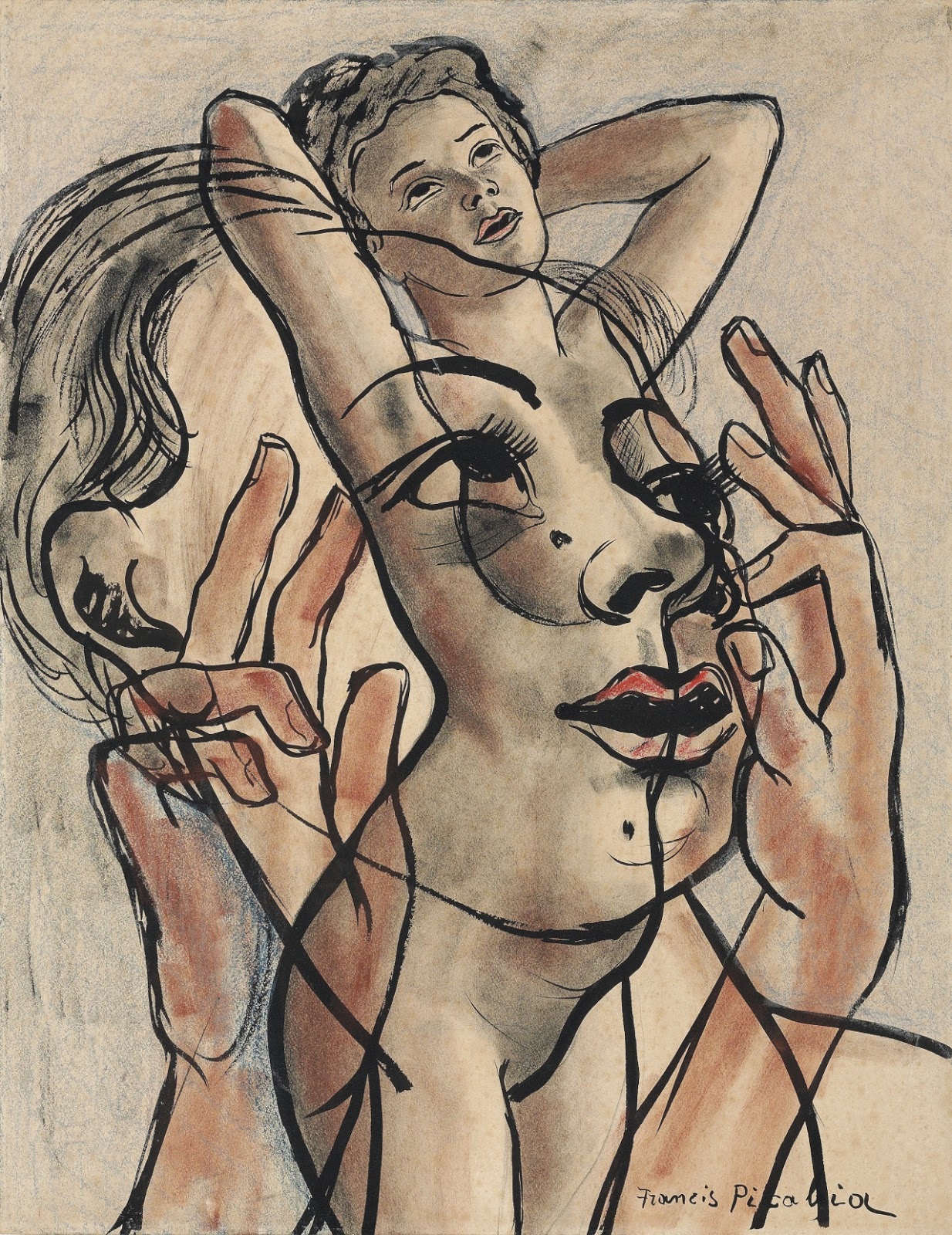

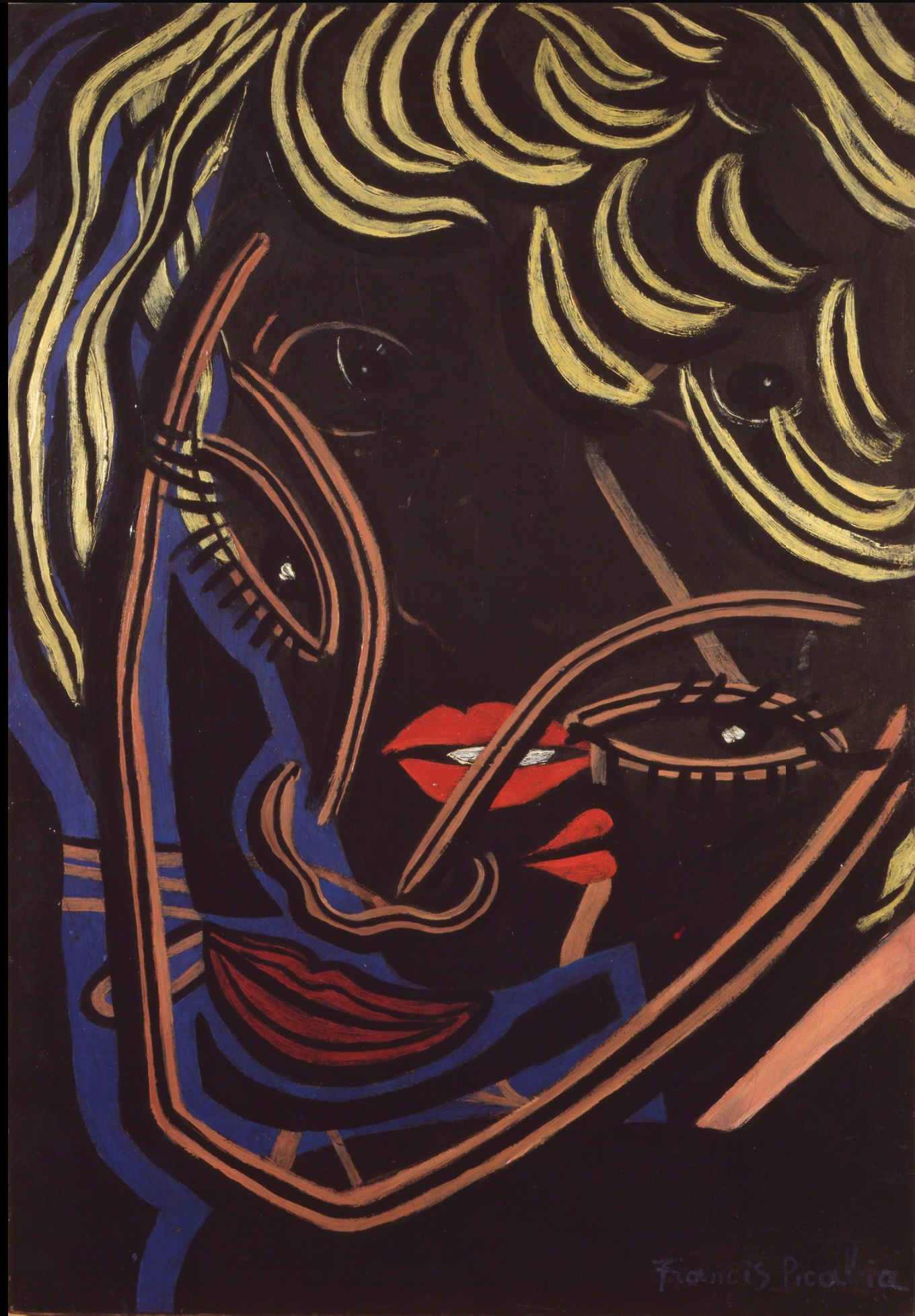

In his ‘Transparencies’ series, Picabia explored the effects of photographic technologies on the psychology of the viewer. He would begin to undermine the effects of the mechanically reproduced image, by overlaying images found in Parisian porn magazines, with religious and spiritual motifs, in an attempt to disrupt the kinds of sterile social conventions he thought mass-produced imagery was imposing upon morality and ethics.

If we suppose that now the idea of human - machine relationships are more ambiguously structured, then our own technological position presents us with the idea of the interface, as the ontological gap between reality and virtual reality seemingly decreases, our desire for the anthropocentric vision is being perturbed further still by forces that emanate from the emotional worlds.

The recent influx of interest in Picabia's, comic-erotic mechanical paintings is testament to the re-emergence of this dialectic relationship between ourselves, our technologies and our sense of religion, morality and sexuality.

Picabia’s consistent inconsistencies, his appropriative strategies, and his stylistic eclecticism, along with his skeptical attitude, make him especially relevant to contemporary artists, philosophers and poets of today.

As we begin to question implicit structural biases and long standing hierarchies of our own times, it may be worth remembering that Picabia sought to travesty rather than transcend modernity by acting out its in-built absurdity, in a form of self-critical contradiction that opposed the classical ideology of his time from the inside out.

Although Picabia was afforded the financial wealth in order to hold this critical position within society for the majority of his career, he nevertheless was a prolific creator who painted in sporadic styles that continue to speak to the contradictions within us, a true anti-artist which is testament to both Picabia’s failure and success.

In his lifetime, Picabia believed that painting had begun its inexorable decline into endless self reflective mass production. Cinematic technologies offered a greater power than print to disrupt the expectations of the audience and to undermine the norms and codes of social conventions. He transferred his 'esprit dada' into a new phase of artistic production which involved - and fetishised more than ever before - the spirit of the machine.

In his ‘Transparencies’ series, Picabia explored the effects of photographic technologies on the psychology of the viewer. He would begin to undermine the effects of the mechanically reproduced image, by overlaying images found in Parisian porn magazines, with religious and spiritual motifs, in an attempt to disrupt the kinds of sterile social conventions he thought mass-produced imagery was imposing upon morality and ethics.

If we suppose that now the idea of human - machine relationships are more ambiguously structured, then our own technological position presents us with the idea of the interface, as the ontological gap between reality and virtual reality seemingly decreases, our desire for the anthropocentric vision is being perturbed further still by forces that emanate from the emotional worlds.

The recent influx of interest in Picabia's, comic-erotic mechanical paintings is testament to the re-emergence of this dialectic relationship between ourselves, our technologies and our sense of religion, morality and sexuality.

Picabia’s consistent inconsistencies, his appropriative strategies, and his stylistic eclecticism, along with his skeptical attitude, make him especially relevant to contemporary artists, philosophers and poets of today.

As we begin to question implicit structural biases and long standing hierarchies of our own times, it may be worth remembering that Picabia sought to travesty rather than transcend modernity by acting out its in-built absurdity, in a form of self-critical contradiction that opposed the classical ideology of his time from the inside out.

Although Picabia was afforded the financial wealth in order to hold this critical position within society for the majority of his career, he nevertheless was a prolific creator who painted in sporadic styles that continue to speak to the contradictions within us, a true anti-artist which is testament to both Picabia’s failure and success.

Further Reading ︎

After 391, Chris Joseph, essay

Timothy Morton, Beautiful Soul Syndrome, video

The Filming of Modern Life: European Avant-Garde Film of the 1920s, By Malcolm Turvey

Aello, MoMA

The Paris Review, article

391, DADA archive