hildegard von bingen

︎Artist, Painting, Philosophy

︎ Ventral Is Golden

hildegard von bingen

︎Artist, Painting, Philosophy

︎ Ventral Is Golden

︎ Ventral Is Golden

"I, the fiery life of divine essence, am aflame beyond the beauty of the meadows."

Hildegard of Bingen (1098-1179), also known as Saint Hildegard and Sibyl of the Rhine, was a German Benedictine abbess, writer, composer, philosopher, Christian mystic, visionary, herbalist and overall polymath, who ruled her own monastery of Rupertsberg, high on a hill in rural Germany.

As was customary at the time, as the tenth child (tithe) of a noble family, Hildegard was dedicated to the church at birth, where her religious education was given to her by the charismatic teenage anchoress named Jutta.

As an anchoress, or 'one who had retired from the world', Jutta lived her life inside the one-room stone shelter of the monastery, closed from the outside world except for one small window, a portal through which her teachings would flow and from where she would educate the daughter's of noble families. In Hildegard's later years, upon Jutta's death, she would take up the role as abbess of Disibodenberg, and in 1141, Hildegard began to find a voice for the visions that had accompanied her from a very young age.

As was customary at the time, as the tenth child (tithe) of a noble family, Hildegard was dedicated to the church at birth, where her religious education was given to her by the charismatic teenage anchoress named Jutta.

As an anchoress, or 'one who had retired from the world', Jutta lived her life inside the one-room stone shelter of the monastery, closed from the outside world except for one small window, a portal through which her teachings would flow and from where she would educate the daughter's of noble families. In Hildegard's later years, upon Jutta's death, she would take up the role as abbess of Disibodenberg, and in 1141, Hildegard began to find a voice for the visions that had accompanied her from a very young age.

“We cannot live in a world that is not our own, in a world that is interpreted for us by others. An interpreted world is not a home. Part of the terror is to take back our own listening, to use our own voice, to see our own light.”

Despite the structural inequalities of the medieval period that rendered it almost impossible for women (or anyone outside of the church) to have their voices heard within society, the religious institutions of the middle ages were perhaps surprisingly for the time, places of relative diversity of thought in relation to natural sciences and to the scribal crafts of women, who in some cases undertook the re-writing of religious texts that predominantly had a male-inflected language.

In Anglo-Saxon England, for example, religious women had an inclusive place in the world of writing and were often educated alongside men in “double-houses,” or co-ed monasteries and schools. This is not to say that these educational institutions didn't have a very real propensity to exclude women from the more progressive social roles of the time, (as with the Roman Church who's less liberal views restricted the voices of women and even prohibited singing in private chambers because of its association with prostitution), but if we broaden our definition of what “writing” meant - to include the entire process of book-making, we find women pushing further against the social conventions in order to share their skills and experiences within the philosophical pursuits of the church and in even democratising the religious experience in the case of Hildegard’s creative approach to writing and composing music.

For many years, Hildegard was reluctant to share her visions, writing "I did not make that known to any person except to a certain few... I sank down beneath a quiet silence... although I did see and hear this, nevertheless because of doubt and a bad opinion and the diversity of men’s words, refused to write for a long time."

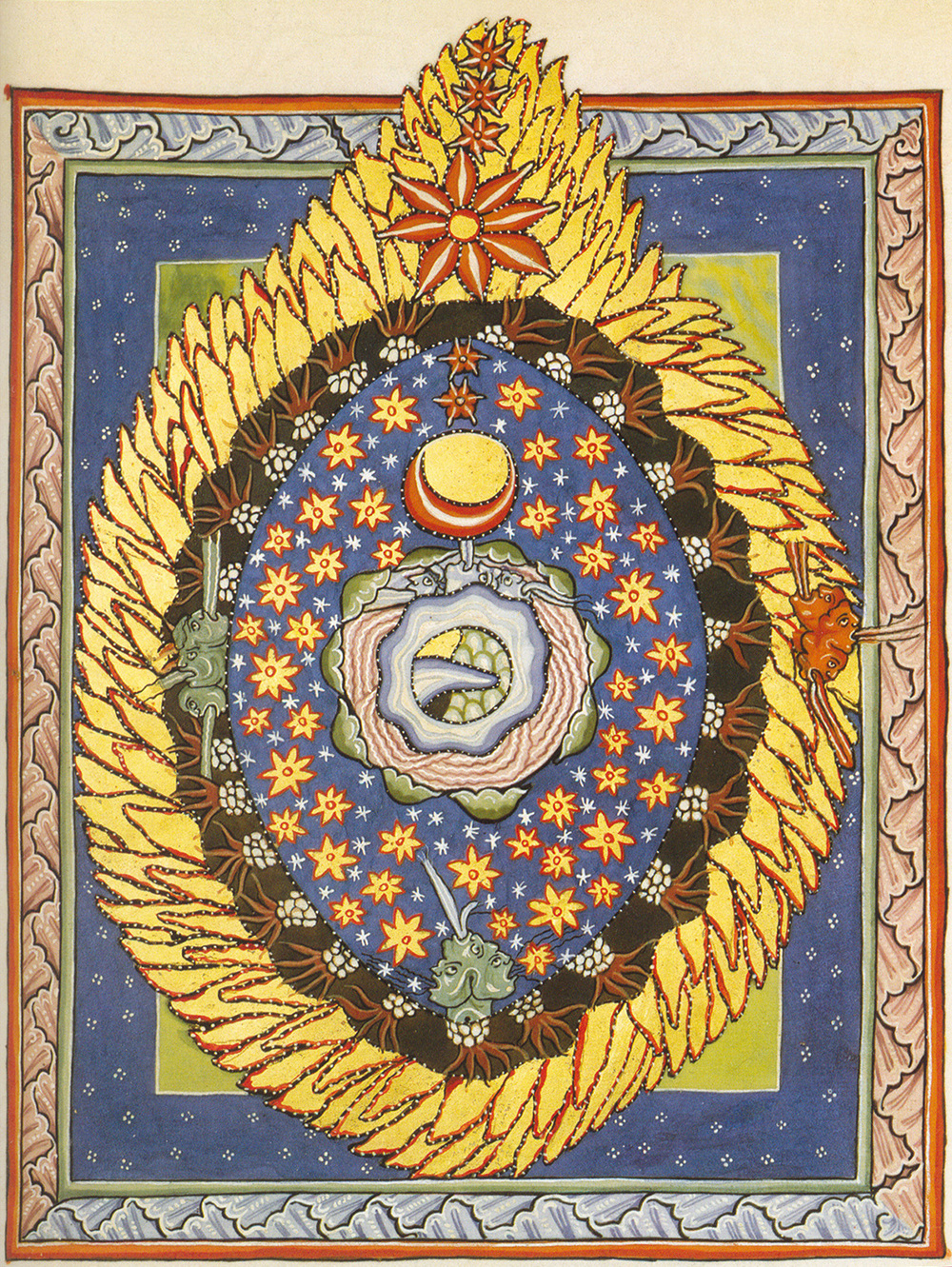

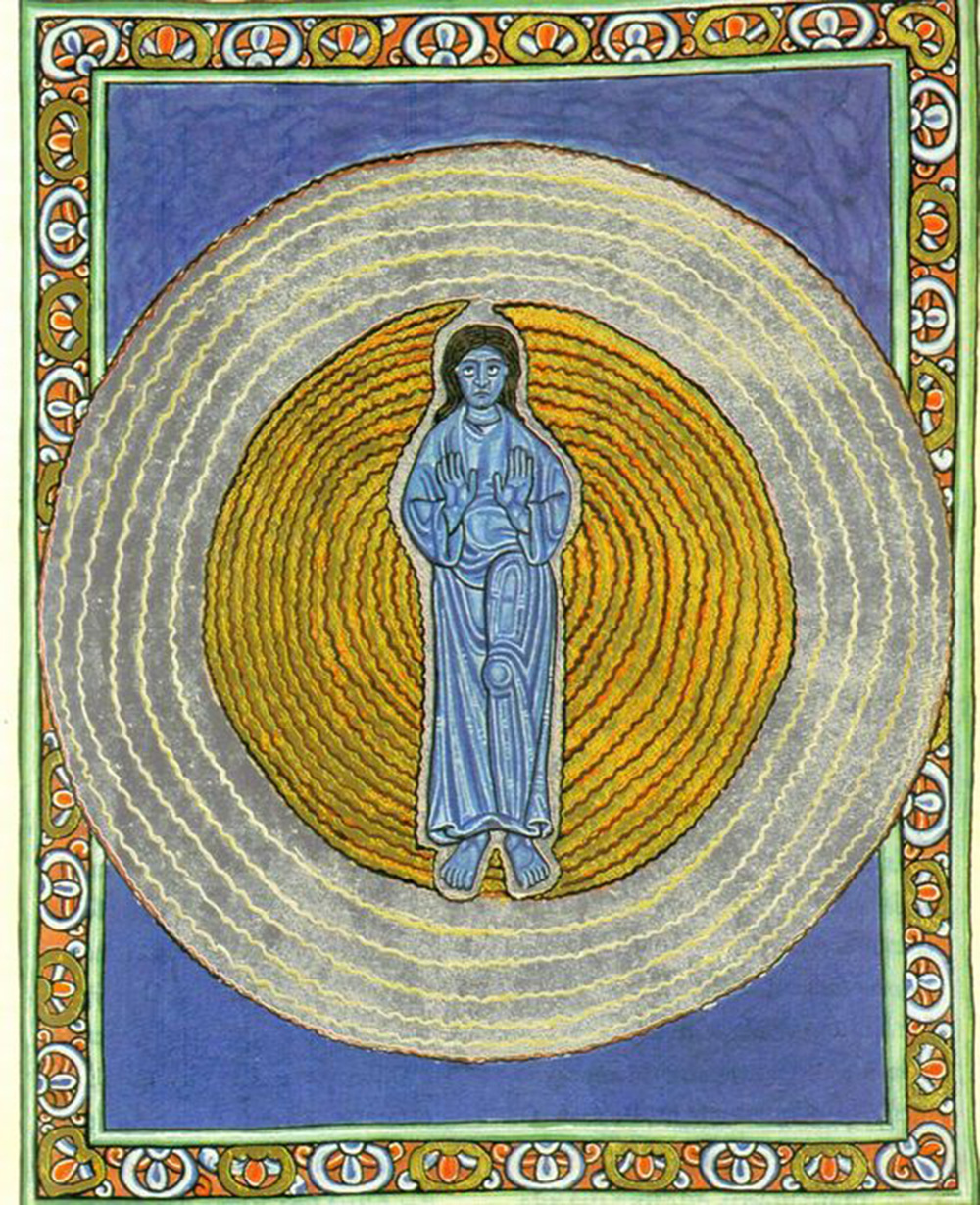

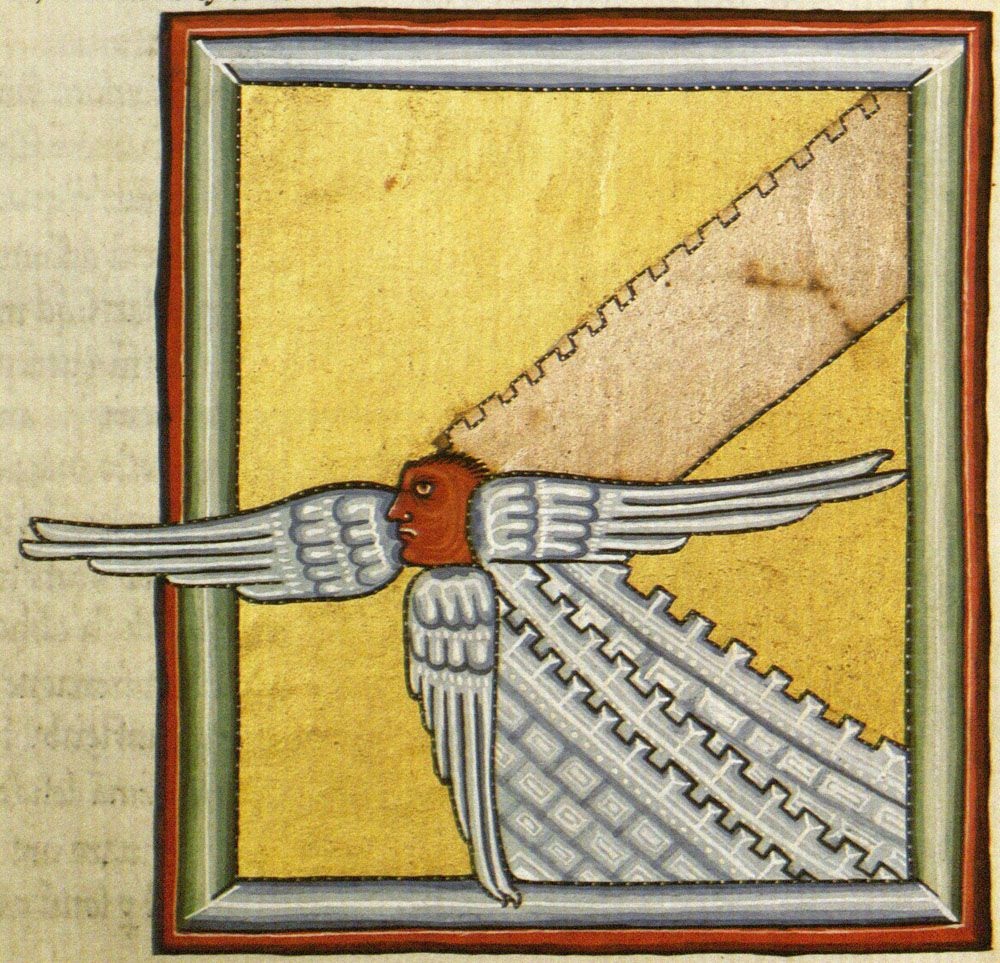

Referring to her visions as 'Reflections of the Living Light' or the 'Scivias', Hildegard's writings received a blessing from Pope Eugene III, leading to a number of women and girls travelling to meet Hildegard at the subsequent creation of a new, all female monastery in Rupertsberg.

Despite being a respected woman of obvious intellect, some scholars question how Hildegard was able to gain the admiration and attention that she did, considering the general social attitude held towards women in the twelfth century. It has been argued that Hildegard's specific use of language to describe her visions (accompanied by the onset of illness brought about by the power of such divine revelations) enabled her to manoeuvre around the oppressive patriarchal views that invalidated the personal revelations of women.

"Although she records her first vision as having occurred at age three, Hildegard does not begin to publicize her visions and seek approval until forty-two years later. The combination of illness and visionary experience presents another interesting aspect to her status as a female religious leader in the Middle Ages. Christian tradition venerates those who suffer patiently. The connection between illness and feminine piety is quite clear: "if sickness is offered as a gift, then pain can be transmuted into the complex pleasure of generosity."

“In addition, it is also considered that Hildegard was the author of the first artificial language system - the Lingua Ignota (Unheard Voice).”

As a method of empowering her position as an influential religious figure, Hildegard had to embody her silent suffering, to become self-effacing so as not to affect the apparent authenticity of her experience. This was accomplished in two ways:

The first was by using the Vox Dei (voice of God) as a technique by which a disassociation could take place, essentially making her insights seem less anecdotal and more revelatory. Something that was nurtured through having a broad knowledge of the scriptures, where subtle intonations were made to biblical references to make the accounts seem more credible in the eyes of the church and to also discreetly criticise the corruption of it.

The second was to truly submerge herself in creative endeavours, embodying and promoting the medieval perspective that the universe was recapitulated in miniature inside of the human body. Not only did she gain recognition for her intellectual and spiritual insights, but she also supplanted her power as a 'political prophetess' by cultivating the nurturing, social principles of science, art and music, creating numerous books on natural science, and at least sixty nine musical compositions relating to 'Viriditas' (Latin for greenness, lushness, freshness, growth, vitality). (Talley)

In addition, it is also considered that she was the author of the first artificial language system Lingua Ignota (Unheard Voice), presumably intended as a universal language containing nouns and adjectives relating to body-parts, illnesses, birds, insects, religious and hierarchical terms, ranks of nobility, craftsmen, days, months, clothing, household instruments and phenomenological observations of many growing processes.

The first was by using the Vox Dei (voice of God) as a technique by which a disassociation could take place, essentially making her insights seem less anecdotal and more revelatory. Something that was nurtured through having a broad knowledge of the scriptures, where subtle intonations were made to biblical references to make the accounts seem more credible in the eyes of the church and to also discreetly criticise the corruption of it.

The second was to truly submerge herself in creative endeavours, embodying and promoting the medieval perspective that the universe was recapitulated in miniature inside of the human body. Not only did she gain recognition for her intellectual and spiritual insights, but she also supplanted her power as a 'political prophetess' by cultivating the nurturing, social principles of science, art and music, creating numerous books on natural science, and at least sixty nine musical compositions relating to 'Viriditas' (Latin for greenness, lushness, freshness, growth, vitality). (Talley)

In addition, it is also considered that she was the author of the first artificial language system Lingua Ignota (Unheard Voice), presumably intended as a universal language containing nouns and adjectives relating to body-parts, illnesses, birds, insects, religious and hierarchical terms, ranks of nobility, craftsmen, days, months, clothing, household instruments and phenomenological observations of many growing processes.

Nowadays, Hildegard is more commonly known for her musical compositions (only acknowledged by contemporary audiences some eight hundred years after her death). With no formal training other than the education she received from the anchoress Jutta, as well as growing up hearing the chants of the Roman mass, she set her own vibrant, colourful verses to music.

Little is known about Hildegard’s compositional process, only that her unorthodox grasp of latin gave her music a complex, multi-varied meaning, more akin in style to a fluid stream-of-consiouness. For Hildegard, music was the place where the spheres of heaven and earth interlocked and harmonious intergration of the human with nature enabled an individual to receive the living light, a feeling of well being.

As a calling to live both the contemplative life and a life of intentionality, to express intimate personal visions in times of seeming inequality and an inability to express the kinds of ideals that lie beyond the physical self, excerpts from Hildegard’s manuscript, The Scivias (’Reflections of the Living Light’ / ‘Know The Ways’) are a timless reminder of the potential within a creative spirit, in dynamic harmony with thoughts and actions;

O fragile human, ashes of ashes, filth of filth! Say and write what you see and hear. But since you are timid in speaking, and simple in expounding, and untaught in writing, speak and write these things not by a human mouth, and not by the understanding of human invention, and not by the requirements of human composition, but as you see and hear them on high in the heavenly places in the wonders of nature. Explain these things in such a way that the hearer, receiving words of their instructor, may expound them in those words, according to that will, vision and instruction. Thus, therefore, O human, speak these things that you see and hear. And write them not by yourself or any other human being, but by the will of That Which Knows, sees, and disposes all things in the secrets of the mysteries.

And holding one another fast, strive together in all these things with the eagerness from above so that the hidden wonders may be revealed. And that this same person does not rely upon themselves but turns with many sighs toward the one that they found in the approach to humility and the intention of good will. You therefore, o mortal, who receive this, not in the disquiet of deceit but in the purity of simplicity, having been directed toward the revealing of hidden things - write what you see and hear.”

![]()

Little is known about Hildegard’s compositional process, only that her unorthodox grasp of latin gave her music a complex, multi-varied meaning, more akin in style to a fluid stream-of-consiouness. For Hildegard, music was the place where the spheres of heaven and earth interlocked and harmonious intergration of the human with nature enabled an individual to receive the living light, a feeling of well being.

As a calling to live both the contemplative life and a life of intentionality, to express intimate personal visions in times of seeming inequality and an inability to express the kinds of ideals that lie beyond the physical self, excerpts from Hildegard’s manuscript, The Scivias (’Reflections of the Living Light’ / ‘Know The Ways’) are a timless reminder of the potential within a creative spirit, in dynamic harmony with thoughts and actions;

O fragile human, ashes of ashes, filth of filth! Say and write what you see and hear. But since you are timid in speaking, and simple in expounding, and untaught in writing, speak and write these things not by a human mouth, and not by the understanding of human invention, and not by the requirements of human composition, but as you see and hear them on high in the heavenly places in the wonders of nature. Explain these things in such a way that the hearer, receiving words of their instructor, may expound them in those words, according to that will, vision and instruction. Thus, therefore, O human, speak these things that you see and hear. And write them not by yourself or any other human being, but by the will of That Which Knows, sees, and disposes all things in the secrets of the mysteries.

And holding one another fast, strive together in all these things with the eagerness from above so that the hidden wonders may be revealed. And that this same person does not rely upon themselves but turns with many sighs toward the one that they found in the approach to humility and the intention of good will. You therefore, o mortal, who receive this, not in the disquiet of deceit but in the purity of simplicity, having been directed toward the revealing of hidden things - write what you see and hear.”

Further Reading ︎

The Secret of the Golden Flower (Commentary by CG Jung).

'Women Scribes: The Technologists of the Middle Ages',

The New Inquiry.

Women as Scribes throughout History.

The Medieval Prophetess Who Used Her Visions to Criticize the Church.

Visions of Power and Influence:

Hildegard of Bingen and the Politics of Mysticism by Lisa Elena Talley.

Scivias Summary and Images Hildegard Von Bingen -

A Very Real Mystic, video.

The Secret of the Golden Flower (Commentary by CG Jung).

'Women Scribes: The Technologists of the Middle Ages',

The New Inquiry.

Women as Scribes throughout History.

The Medieval Prophetess Who Used Her Visions to Criticize the Church.

Visions of Power and Influence:

Hildegard of Bingen and the Politics of Mysticism by Lisa Elena Talley.

Scivias Summary and Images Hildegard Von Bingen -

A Very Real Mystic, video.