john austen

︎Artist, Illustration, Graphic Design, Art Nouveau

︎ Ventral Is Golden

john austen

︎Artist, Illustration, Graphic Design, Art Nouveau

︎ Ventral Is Golden

“Give thy thoughts no tongue.”

- Hamlet.

- Hamlet.

John Archibald Austen (1886 - 1948) was an english illustrator and ‘Book Decorator’, greatly influenced by the styles of Art Nouveau.

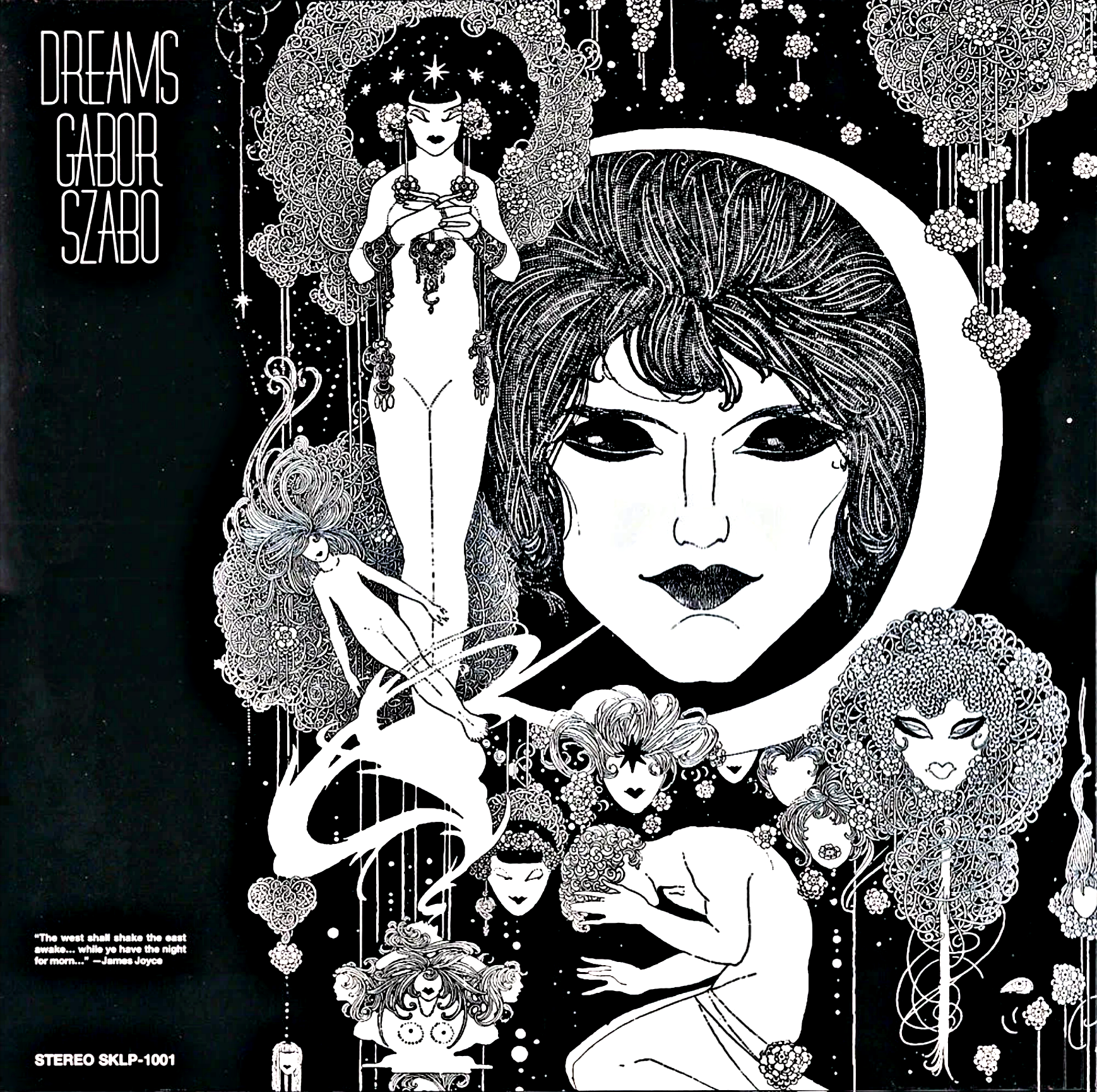

He utilised several techniques in his illustrations and also produced engravings for graphic design, advertisments, several posters & numerous dust wrappers, often being able to adapt his heavily stylised works to suit the commercial or literary contents of the era. His work was also posthumuously used on the vinyl cover of ‘Dreams’ (1964), by renouned Hungarian musician Gabor Szabo.

Austen also moved in similar circles to occultists such as the Irish stained glass maker and illustrator Harry Clarke, and illustrators Alan Odle and Austin Osman Spare, sharing with them an interest in Arabic, Persian, Mesopotamian, Indian, Jewish and Egyptian folkloric mysticism, most commonly associated with Spare and his own conception of philosophical magic called the Zos Kia Cultus.

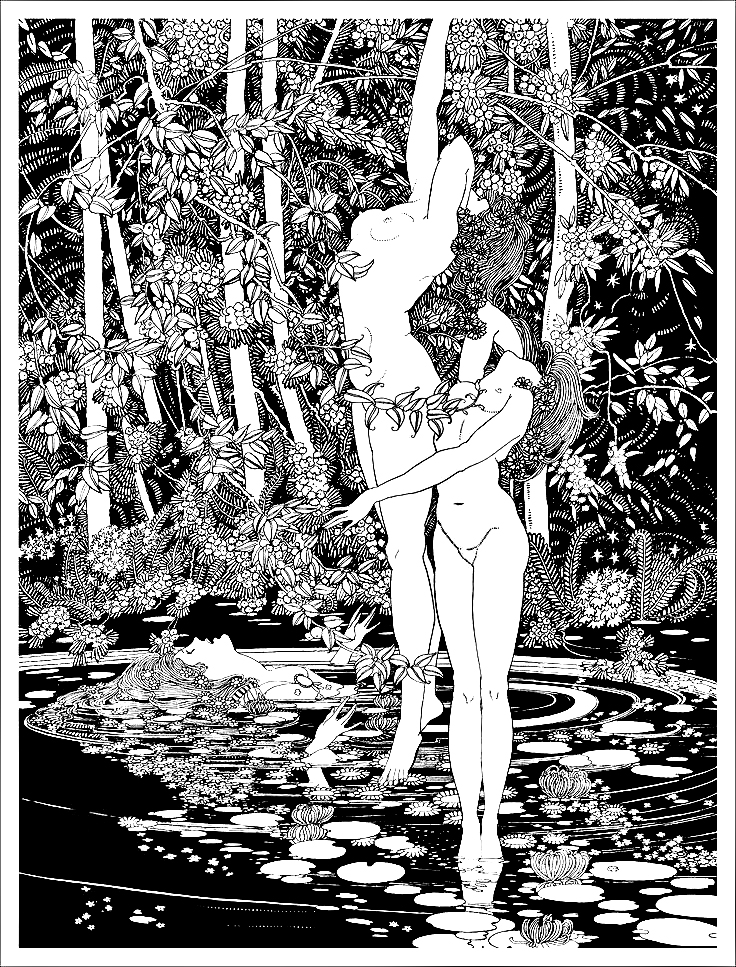

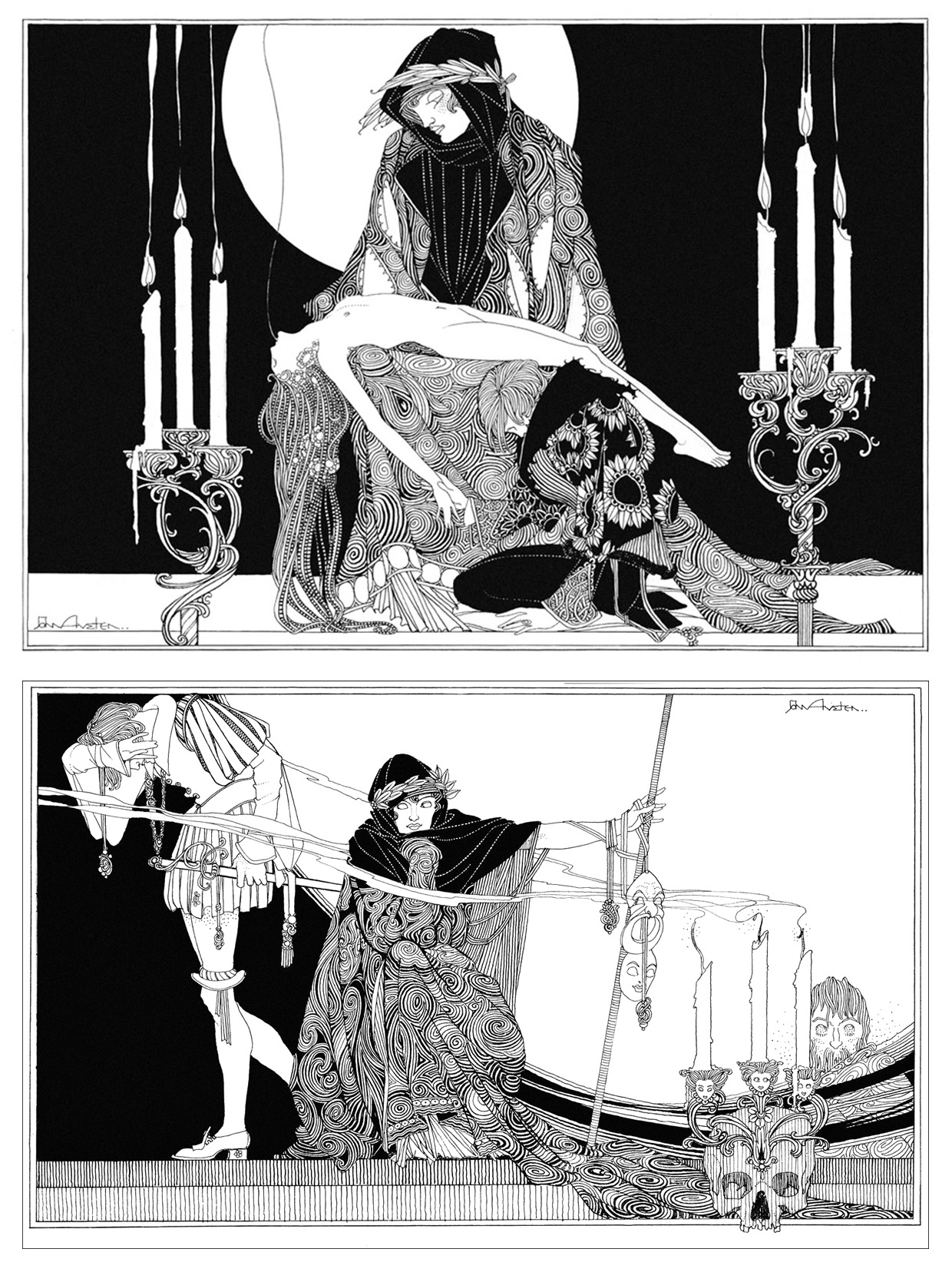

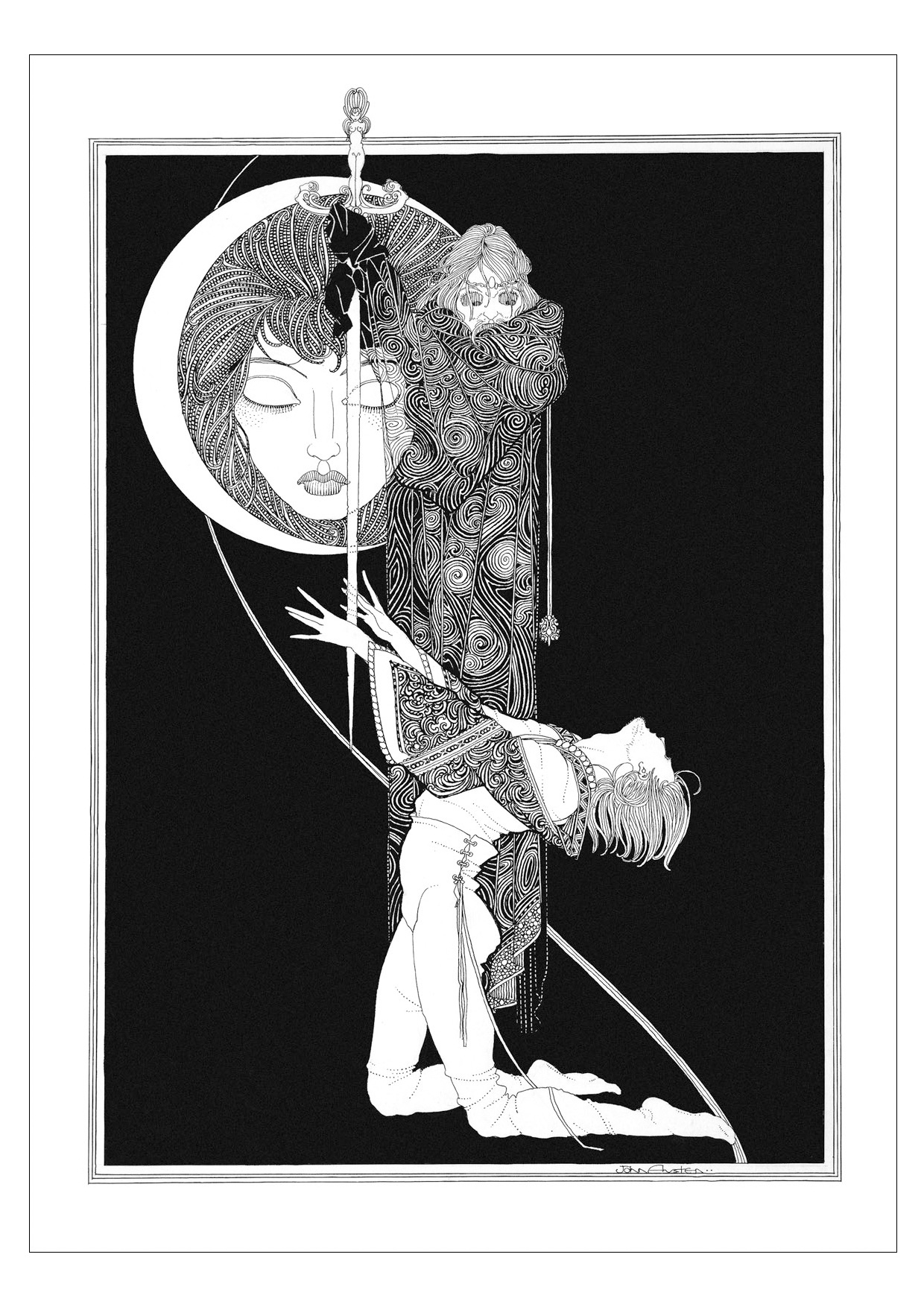

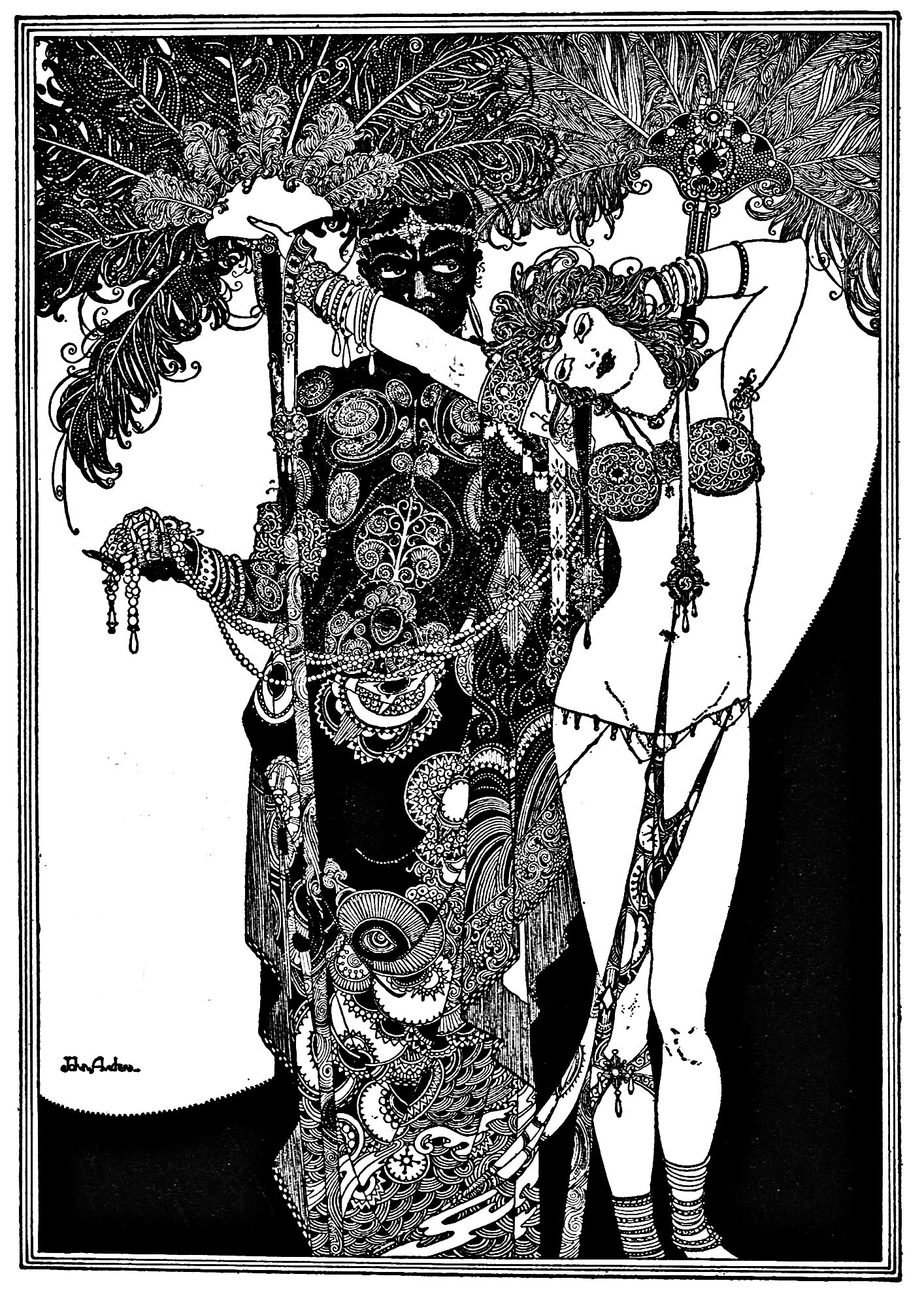

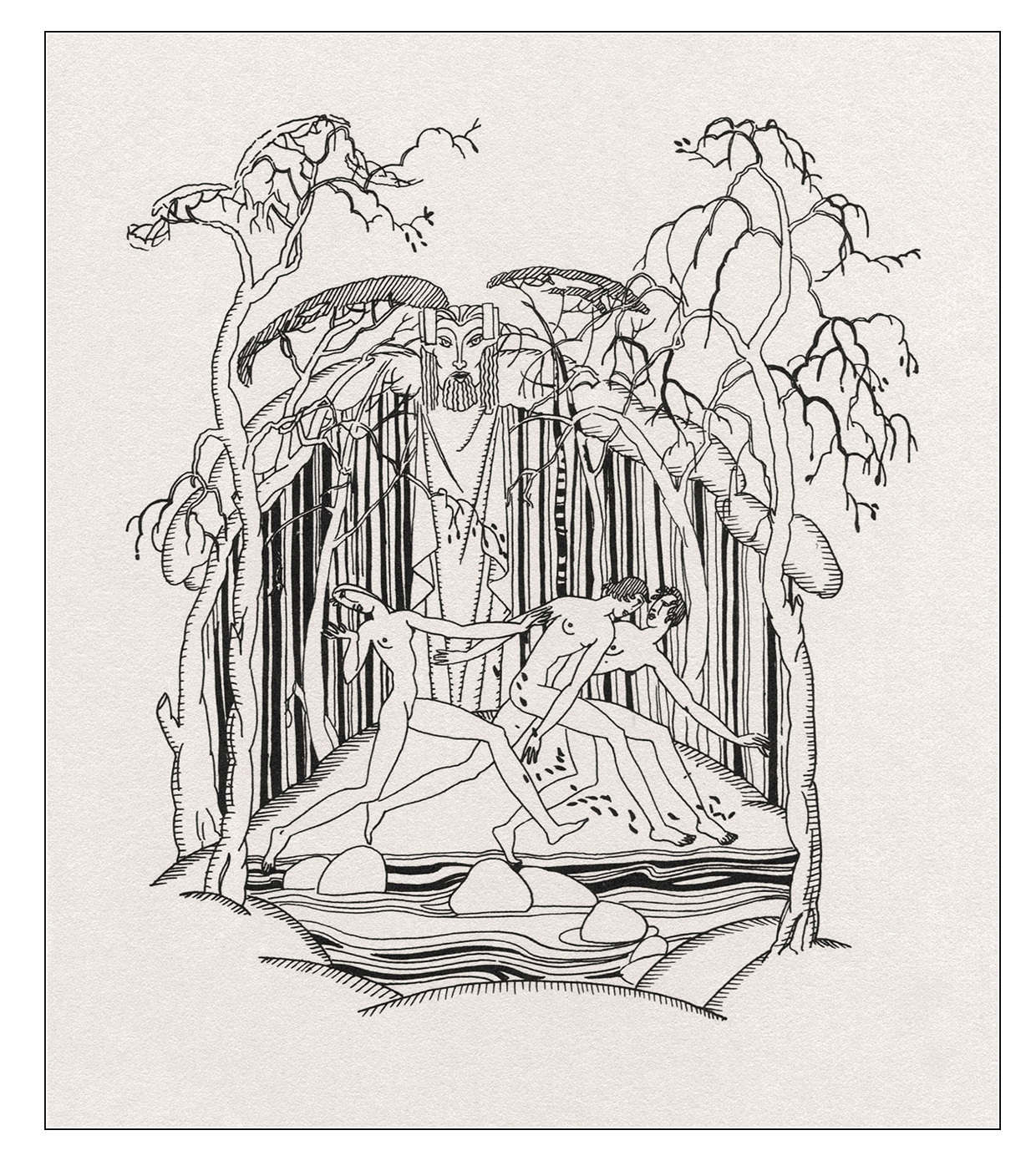

The classical and esoteric literary world seemed to be a habitable domain for Austen’s visual expressions. Alongside his works in 'Daphnis and Chloe', a coming of age romance written by Greek playwrite Longus, and 'The Frogs', a satirical Greek comedy about Dionysus, his early Art Nouveau visualisations were the foundations of his apporach to using stark contrast as composition. Through initiating himself into the aestheics of Aubrey Beardsley, Austen, for a 1922 edition of Shakespeare’s ‘Hamlet’ evoked a seemless blend of the sensual and macabre thematically portrayed in the earlier publication of Oscar Wilde’s, Salomé.

He utilised several techniques in his illustrations and also produced engravings for graphic design, advertisments, several posters & numerous dust wrappers, often being able to adapt his heavily stylised works to suit the commercial or literary contents of the era. His work was also posthumuously used on the vinyl cover of ‘Dreams’ (1964), by renouned Hungarian musician Gabor Szabo.

Austen also moved in similar circles to occultists such as the Irish stained glass maker and illustrator Harry Clarke, and illustrators Alan Odle and Austin Osman Spare, sharing with them an interest in Arabic, Persian, Mesopotamian, Indian, Jewish and Egyptian folkloric mysticism, most commonly associated with Spare and his own conception of philosophical magic called the Zos Kia Cultus.

The classical and esoteric literary world seemed to be a habitable domain for Austen’s visual expressions. Alongside his works in 'Daphnis and Chloe', a coming of age romance written by Greek playwrite Longus, and 'The Frogs', a satirical Greek comedy about Dionysus, his early Art Nouveau visualisations were the foundations of his apporach to using stark contrast as composition. Through initiating himself into the aestheics of Aubrey Beardsley, Austen, for a 1922 edition of Shakespeare’s ‘Hamlet’ evoked a seemless blend of the sensual and macabre thematically portrayed in the earlier publication of Oscar Wilde’s, Salomé.

One of Austen’s most stunning illustrations is that of 'Scheherazade', the female polymath and narrator of the Arabian literary classic, 1001 Nights.

As the story goes, Scheherazade, against the wishes of her father, volunteered to marry the king in an attempt to prevent him from beheading a new wife everyday until he was sure that he could never be dishonoured by another woman. Scheherazade captivated the King by recounting a story. As the day passed and the story had not yet finished, the king, curious to know how the story would unfold, spared her life. Scheherazade did this every day until one thousand and one nights had passed. The King understood the nature of his own pain and was able to recover some sense of morality and compassion.

The significance of Scheherazade’s decision to risk her life in order to save the lives of others can be considered a poignant reminder of how fantasy and stroy-telling are enough to dispell the dominator values of seemingly unchanging, monolithic attitudes regarding control.

Although an obvious proponent of the book and the story form, Austen also expressed some contempt for it, recognising (like Scheherazade did) that the context in which the story exists can be necessarily a repressive one, which both elevates and alienates the storyteller.

He once wrote, “And it is no less a matter for regret, that we illustrators in this machine civilization have lost their freedom from control; no longer do we, in our cells, have full sovereignty over our craft, but we must submit to this and that power. No longer do we weave our letters and our drawings and our bindings into one masterly pattern. We are happy, having made our drawings in record time, to be allowed to hand them over to a mysterious potentate who puts them into a machine with type and paper and plenty of ink, round go the wheels, and glory be... For this business of book-making is, after all, a visual art, depending on the eye alone for the just appreciation of its niceties, and no amount of typographical learning will supply that which only the artist can supply, right judgment—form. It is not the machine that is at fault, for our mechanical methods can and do produce real books, masterpieces of great beauty, it is the mind in control that makes or mars the result.”

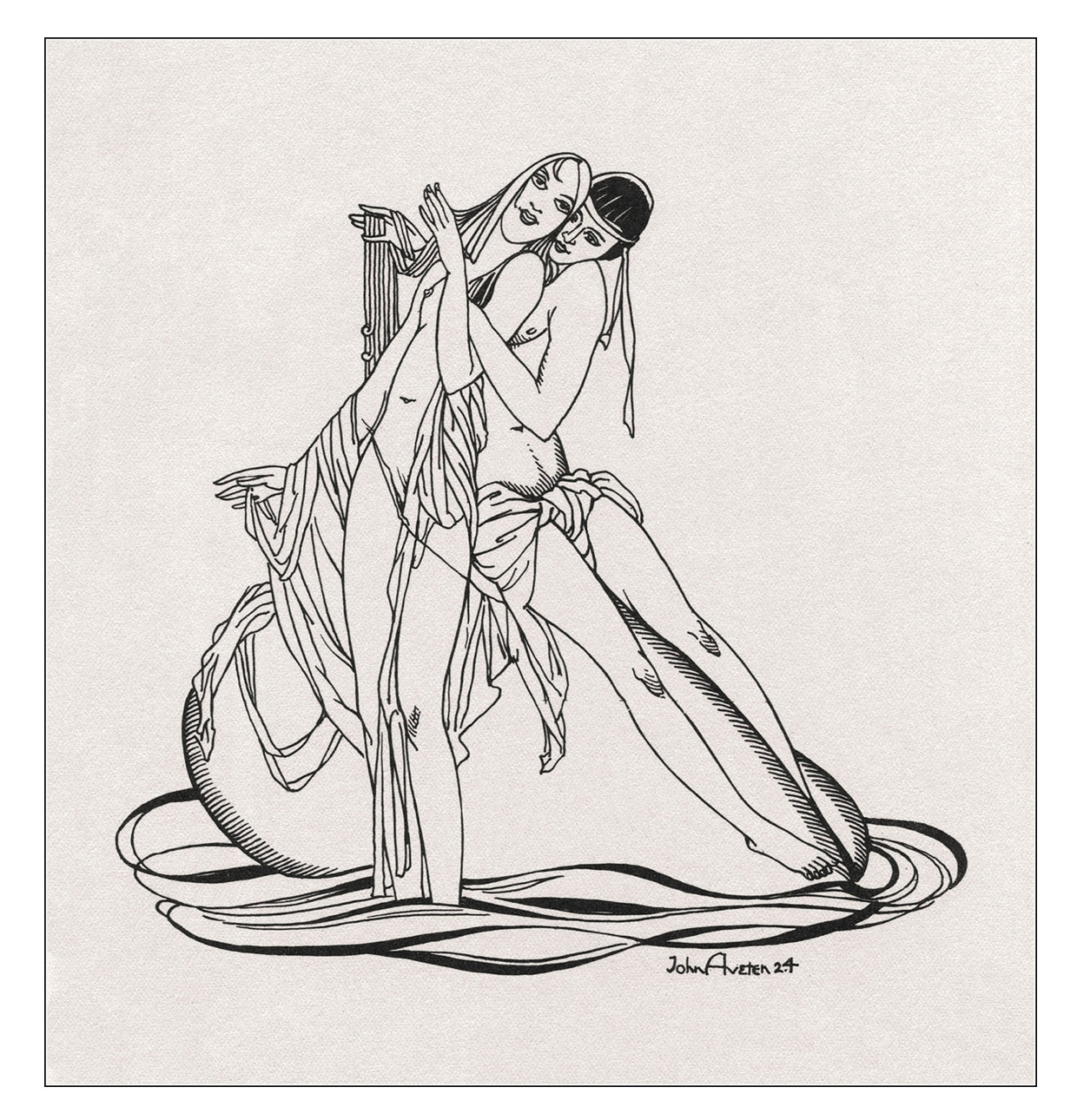

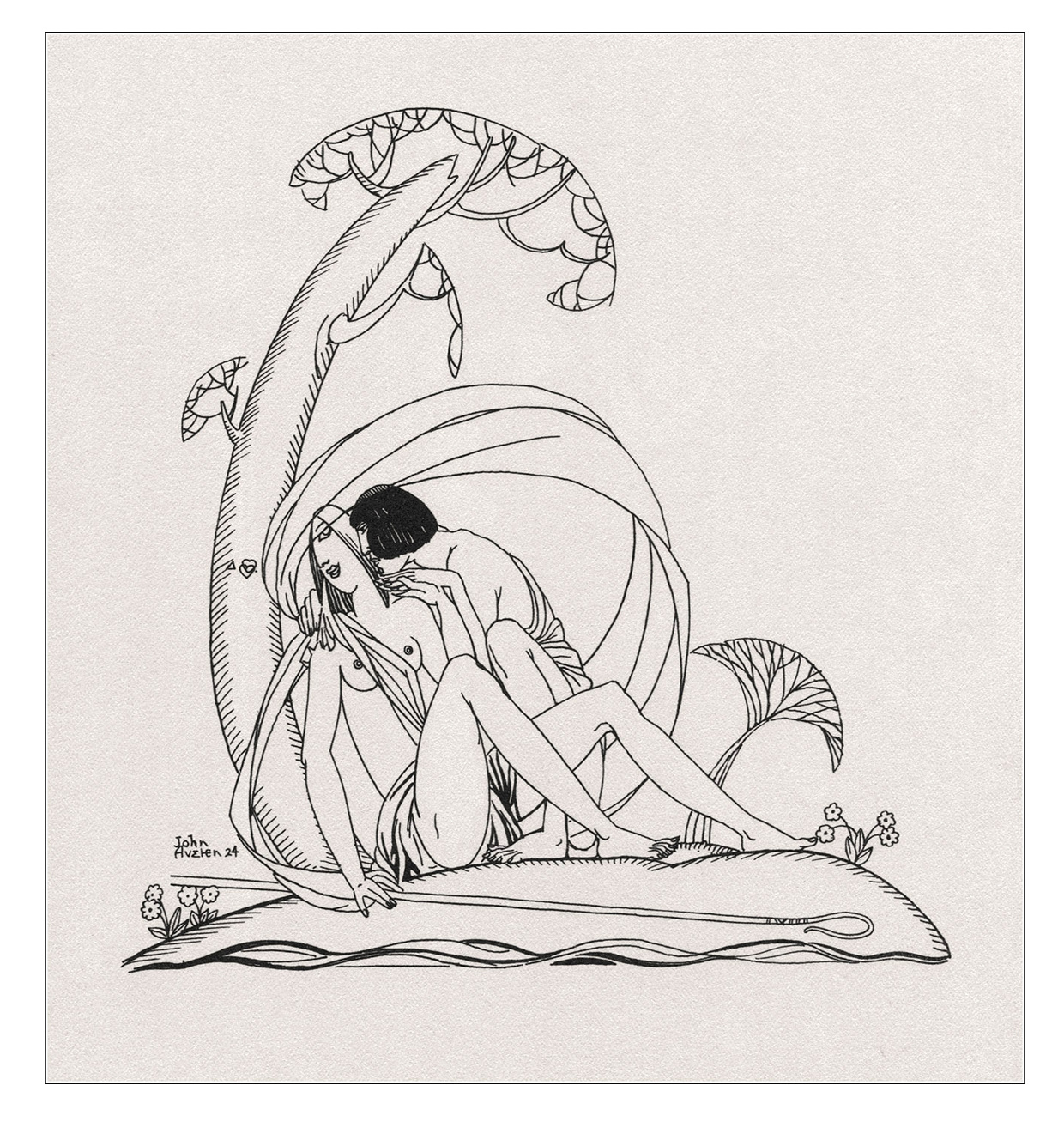

Later, Austen’s style began to move away from the aesthetics of Art Nouveau and towards a more geometric Art Deco impulse, where the heavy contast in composition gave way to his delicate line drawings. It attested to Austen's ability as a clear conveyor of visual narratives to maintain the central essence of these stories whilst also retaining his distinctly personal bond with ancient mythos and occult symbolism.

As the story goes, Scheherazade, against the wishes of her father, volunteered to marry the king in an attempt to prevent him from beheading a new wife everyday until he was sure that he could never be dishonoured by another woman. Scheherazade captivated the King by recounting a story. As the day passed and the story had not yet finished, the king, curious to know how the story would unfold, spared her life. Scheherazade did this every day until one thousand and one nights had passed. The King understood the nature of his own pain and was able to recover some sense of morality and compassion.

The significance of Scheherazade’s decision to risk her life in order to save the lives of others can be considered a poignant reminder of how fantasy and stroy-telling are enough to dispell the dominator values of seemingly unchanging, monolithic attitudes regarding control.

Although an obvious proponent of the book and the story form, Austen also expressed some contempt for it, recognising (like Scheherazade did) that the context in which the story exists can be necessarily a repressive one, which both elevates and alienates the storyteller.

He once wrote, “And it is no less a matter for regret, that we illustrators in this machine civilization have lost their freedom from control; no longer do we, in our cells, have full sovereignty over our craft, but we must submit to this and that power. No longer do we weave our letters and our drawings and our bindings into one masterly pattern. We are happy, having made our drawings in record time, to be allowed to hand them over to a mysterious potentate who puts them into a machine with type and paper and plenty of ink, round go the wheels, and glory be... For this business of book-making is, after all, a visual art, depending on the eye alone for the just appreciation of its niceties, and no amount of typographical learning will supply that which only the artist can supply, right judgment—form. It is not the machine that is at fault, for our mechanical methods can and do produce real books, masterpieces of great beauty, it is the mind in control that makes or mars the result.”

Later, Austen’s style began to move away from the aesthetics of Art Nouveau and towards a more geometric Art Deco impulse, where the heavy contast in composition gave way to his delicate line drawings. It attested to Austen's ability as a clear conveyor of visual narratives to maintain the central essence of these stories whilst also retaining his distinctly personal bond with ancient mythos and occult symbolism.

“”

“These self-portraits, while amusing us, bring if not a pang of envy, certainly a feeling of regret that their calm unhurried lot is denied to us, for while these old monks could and did spend their lives wandering from gilded initial to prayer, and from prayer to bed - we rush the completion of our nth volume over breakfast.“ - John Austen.

Further Reading ︎

The Frogs, by Aristophanes

1001 Nights : Bartleby.com

John Austen & The Inseperables, Dorothy Richardson, 1930.

Unveiling Scheherazade: Feminist Orientalism in the International Alliance of Women, 1911-1950

Zos Kia Cultus, Osman Austin Spare