︎ Sculpture, Fashion, Culture, Article

︎ Ventral Is Golden

︎ Sculpture, Fashion, Culture, Article

︎ Ventral Is Golden

︎ Ventral Is Golden

"Kanto-orowa-yaku-saku-no-arankep-shinep-ka-isam".

“Everything in this world has a role to play.” - Ainu proverb.

“Everything in this world has a role to play.” - Ainu proverb.

The Jōmon Period is the earliest historical era of Japanese history which formalised around 14,500 BCE, coinciding with the Neolithic Period in Europe and Asia, and existed in six sub-periods, before ending around 300 BCE, as the Yayoi Period of Japanese history began and the mass agriculture of rice crops started to shape social and political life.

Jōmon (meaning ‘cord-pattern’) is particularly notable for its elaborate ceramic style from where it takes its name. It is considered the longest lasting ceramic tradition in the world, with some artefacts being around 14,000 years old.The later Jōmon periods saw vessels developing into ever more complex designs, showing remarkable skill and aesthetic sensibilities, as well as stylistic diversity of wares from different regions, all expressing local beliefs about cosmology, ritual, song, dance, dress and food preparation.

Archaeologists call this kind of vessel ‘ka’en’, thought to have meant ‘fire-flame’ in Japanese, because their tops stylistically resemble flames and were generally used for cooking.

Jōmon (meaning ‘cord-pattern’) is particularly notable for its elaborate ceramic style from where it takes its name. It is considered the longest lasting ceramic tradition in the world, with some artefacts being around 14,000 years old.The later Jōmon periods saw vessels developing into ever more complex designs, showing remarkable skill and aesthetic sensibilities, as well as stylistic diversity of wares from different regions, all expressing local beliefs about cosmology, ritual, song, dance, dress and food preparation.

Archaeologists call this kind of vessel ‘ka’en’, thought to have meant ‘fire-flame’ in Japanese, because their tops stylistically resemble flames and were generally used for cooking.

Today, most Japanese historians agree on the strong possibility that the Jōmon were not a single homogeneous people, but instead consisted of multiple heterogeneous groups such as the Ainu and Ryukyuans, who were the earliest indigenous, hunter-gatherer cultures of Japan. The prevailing cultural myth in modern day Japan however portrays these people as ‘noble savages’, subjecting them to long periods of discrimination and cultural assimilation in an attempt to unify the character of Japan, which subsequently has seriously affected global recognition of Jōmon art and pottery. Of the 24,000 people on Hokkaido for example, who are still considered Ainu, only a very few speak Ainu or practice the religion. The exact number is not known, as many either hide their Ainu origin or are unaware of it (Cultural Survival).

DNA research shows that the modern day populations in the north of Japan (the Ainu people of Hokkaido) and in the south (the Ryukyuans of Okinawa and Ryukyu islands) are genetically connected to the ancestors of the Jōmon people, who themselves originated from somewhere around the Lake Baikal region in Russia, 24,000 years ago.

Although migrations and DNA admixtures are a complex story, experts seem to conclude that the ancestors of the Jōmon were modern humans who arrived in the archipelago during the Late Pleistocene Ice Ages, about 40,000 years ago, via land bridges caused by worldwide lower sea levels, that connected the mainland to Okinawa and Hokkaido. Which is evidenced in the cross cultural similarities and facial types between the Japanese and Siberian Ainu.

Although migrations and DNA admixtures are a complex story, experts seem to conclude that the ancestors of the Jōmon were modern humans who arrived in the archipelago during the Late Pleistocene Ice Ages, about 40,000 years ago, via land bridges caused by worldwide lower sea levels, that connected the mainland to Okinawa and Hokkaido. Which is evidenced in the cross cultural similarities and facial types between the Japanese and Siberian Ainu.

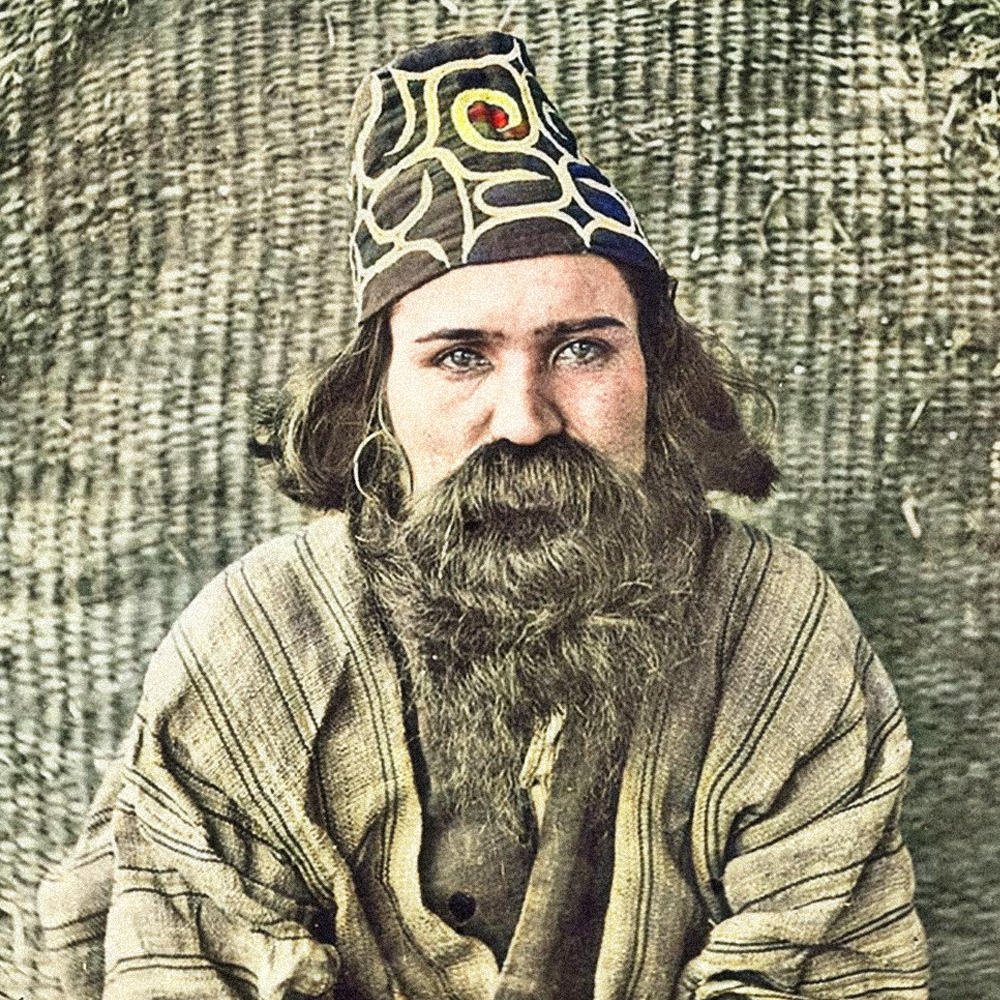

︎ "Ainu leader." Department of Anthropology, Japanese exhibit, 1904 World's Fair..

︎ "Ainu leader." Department of Anthropology, Japanese exhibit, 1904 World's Fair..

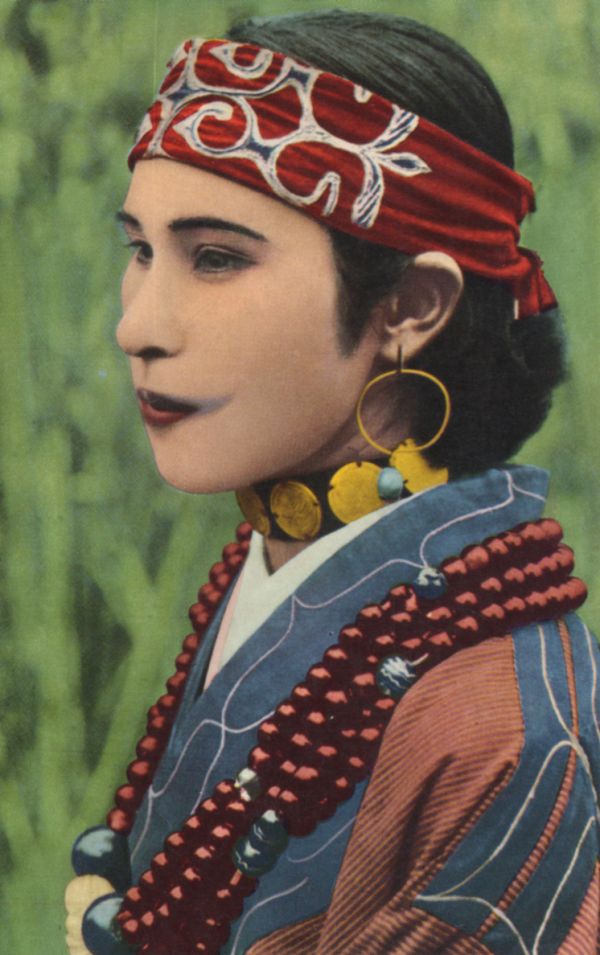

︎ Ainu postcard collection, recoloured. - Thomas Murray, Ethnographer.

︎ Ainu postcard collection, recoloured. - Thomas Murray, Ethnographer.

The Ainu had been seeking recognition as an Indigenous People of Japan in order to protect their distinct culture and increase sensitivity to the historical injustices that ‘unification’ has had upon their identity. Until recently, the Japanese government had not officially recognised the existence of an Indigenous People. Instead, the government characterised the Ainu as an ethnic minority group and asserted that, as individuals only, the Ainu were entitled to equal protection under the Japanese constitution. Accordingly, the government denied collective Aboriginal rights to the Ainu.

It was not until 1997 that a Japanese law was passed, giving official recognition to Ainu language and culture. (New Wolrd Encyclopedia).

Today, although in official documents both names are used, many Ainu dislike the term Ainu because of its derogetory association in the Japanese language, and prefer instead to identify themselves as Utari (’comrade’ in their own language).

This is an all too similar story throughout modern history as indigenous communities suffer persecution through cultural assimilation into a national identity. From the Amazigh of North Africa, the Maya of mesoamerica, and countless others.

In the late twentieth century, a speculation also arose that people of the Jōmon group, ancestral to the Ainu, may have been among the first to settle in North America. Although controversial amongst academics, this theory is based largely on skeletal remains and cultural evidence among tribes living in the western part of North America and certain parts of Latin America. This example is still debated, but it is possible that North America had several peoples among its early settlers and that the Ainu may have been among them.

The Ainu are considered to be one of the earliest continuous world cultures with only the Australian Aborigines and the San (Kalahari Bushmen) being in this select group. Through the postcard collection of independant Ethnographer Thomas Murray, we may access a dimension of humanity’s pre-history that focusses less of tribal warfare and more on hunter-gatherer communities being artisans and culture bearers, who dedicated time to understanding their relationship to the natural world, often through delicate artistic expressions that defy even the most alluring aspects of national and technological ‘progess’.

It was not until 1997 that a Japanese law was passed, giving official recognition to Ainu language and culture. (New Wolrd Encyclopedia).

Today, although in official documents both names are used, many Ainu dislike the term Ainu because of its derogetory association in the Japanese language, and prefer instead to identify themselves as Utari (’comrade’ in their own language).

This is an all too similar story throughout modern history as indigenous communities suffer persecution through cultural assimilation into a national identity. From the Amazigh of North Africa, the Maya of mesoamerica, and countless others.

In the late twentieth century, a speculation also arose that people of the Jōmon group, ancestral to the Ainu, may have been among the first to settle in North America. Although controversial amongst academics, this theory is based largely on skeletal remains and cultural evidence among tribes living in the western part of North America and certain parts of Latin America. This example is still debated, but it is possible that North America had several peoples among its early settlers and that the Ainu may have been among them.

The Ainu are considered to be one of the earliest continuous world cultures with only the Australian Aborigines and the San (Kalahari Bushmen) being in this select group. Through the postcard collection of independant Ethnographer Thomas Murray, we may access a dimension of humanity’s pre-history that focusses less of tribal warfare and more on hunter-gatherer communities being artisans and culture bearers, who dedicated time to understanding their relationship to the natural world, often through delicate artistic expressions that defy even the most alluring aspects of national and technological ‘progess’.

Like most Stone Age cultures from around the world, there was a matrifocal organisation of community life, a goddess centred practice that infused notions of fertility with the fertility of the land, as communities began to settle and climates became more temperate around 4000BC, this precipitated a gradual transition from nomadic to sedentary lifestyles. The Jōmon era was no different. Technologies brought into Japan relating to rice cultivation at this time, in some sense, seeded the demise of the Ainu, who never took to large-scale farming techniques.

It has also been suggested by some historians that military organisation is often a symptom of the psychological need to protect food surplus and could have been a factor in the transition away from animistic symbolism of hunter-gatherer communities.

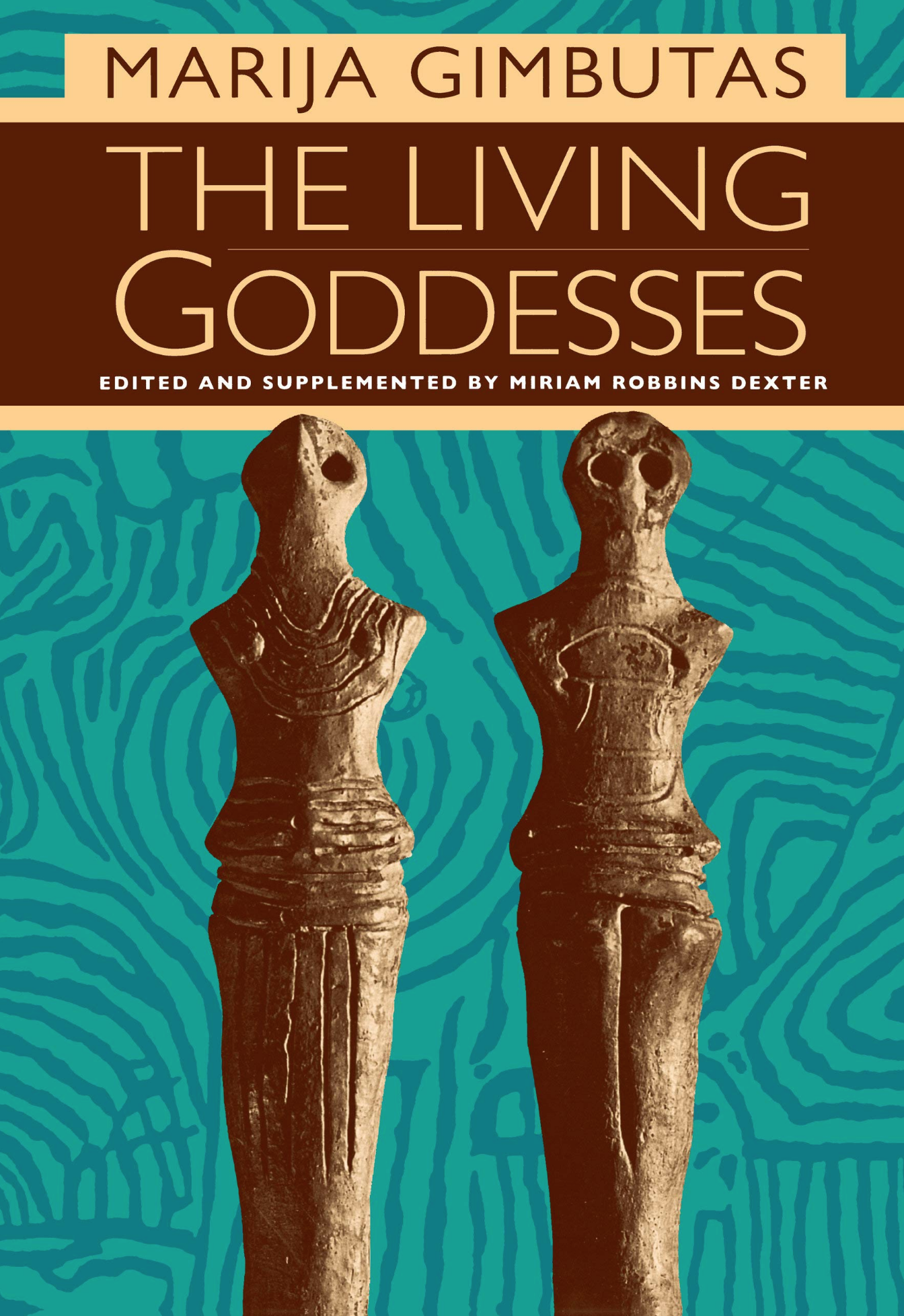

Prominent Lithuanian archeologist, the late Marija Gimbutas, who revived the idea of pre-historical, peace-loving, goddess oriented cultures, nurtured an approach to archeology that was also interdisciplinary. She stated that all artefacts of material culture, from pottery to clothing to tattooing, needed to be analysed from the point of view of ideology, in the sense that it is necessary to widen the scope to include an overlying web of folklore and comparative mythology, placing the symbols into a cognitive framework of the people who made them. It was from this approach that Gimbutas coined the term ‘archaomythology’.

The historical view of Gimbutas, which has since gained more evidence and support, was that hunter-gatherer societies of south eastern Europe, during paleolithic eras, worshipped what were overwhelmingly female deities, and their values emphasised nonviolence and a reverence for nature. This view encompassed the known world before the onset of the Bronze Age began to introduce more advanced weaponry and a rise in sun oreinted, military sysmbolism. Prior to this period, it has been suggested for upto 40,000 years, the central focus of religious thought was of the fertility goddess, known archeologically as ‘the Venus figurines’.

It has also been suggested by some historians that military organisation is often a symptom of the psychological need to protect food surplus and could have been a factor in the transition away from animistic symbolism of hunter-gatherer communities.

Prominent Lithuanian archeologist, the late Marija Gimbutas, who revived the idea of pre-historical, peace-loving, goddess oriented cultures, nurtured an approach to archeology that was also interdisciplinary. She stated that all artefacts of material culture, from pottery to clothing to tattooing, needed to be analysed from the point of view of ideology, in the sense that it is necessary to widen the scope to include an overlying web of folklore and comparative mythology, placing the symbols into a cognitive framework of the people who made them. It was from this approach that Gimbutas coined the term ‘archaomythology’.

The historical view of Gimbutas, which has since gained more evidence and support, was that hunter-gatherer societies of south eastern Europe, during paleolithic eras, worshipped what were overwhelmingly female deities, and their values emphasised nonviolence and a reverence for nature. This view encompassed the known world before the onset of the Bronze Age began to introduce more advanced weaponry and a rise in sun oreinted, military sysmbolism. Prior to this period, it has been suggested for upto 40,000 years, the central focus of religious thought was of the fertility goddess, known archeologically as ‘the Venus figurines’.

︎ The Living Goddess.

︎ Civilisation of the Goddess: The World of Old Europe.

The volumptuous forms of the Venus figurines have been found throughout Europe and as far east as Siberia (thought to be the ancestral home of the Jōmon). Their significance rests largely upon the notion of religion and spirituality being a form of celebration of the natural world, through which social customs were formed.

A comprehensive part of the Jōmon material culture are known as the Dogū (土偶). The Dogū, literally meaning ‘earth figure’ are commonly referred to as the ‘Venus of the Jōmon’ due to their volumptuous forms and feminine features, often depicting various stages of pregnancy. More than 20,000 Dogū have been found across the Japanese archipelago.

![]()

A comprehensive part of the Jōmon material culture are known as the Dogū (土偶). The Dogū, literally meaning ‘earth figure’ are commonly referred to as the ‘Venus of the Jōmon’ due to their volumptuous forms and feminine features, often depicting various stages of pregnancy. More than 20,000 Dogū have been found across the Japanese archipelago.

There is much debate about their ritual function, as there are no written texts from these periods of history. They do however share patterns of being ritualistically broken or burried underneath important communal and spiritual sites, which is why they are very rare to find fully intact.

The Dogū are unique to this period of the Stone Age, as their production ceased by the 3rd century BCE. Their strong association with fertility and mysterious markings ‘tattooed’ onto their clay bodies suggest their potential use in spiritual rituals. Besides Dogū, this period also saw the production of phallic stone objects and standing stone circles, which may have been a part of the same fertility rituals and beliefs linking to astrology.

Images of the female body as symbols of fertility are encountered in many parts of the world in the Neolithic period, presenting features unique to the regions and cultures that produced them. The preoccupation with fertility was increasingly twofold, namely the fertility of women and that of the land, as some people began cultivating their food supply and transitioning to a settled agricultural way of life.

![]()

The Dogū are unique to this period of the Stone Age, as their production ceased by the 3rd century BCE. Their strong association with fertility and mysterious markings ‘tattooed’ onto their clay bodies suggest their potential use in spiritual rituals. Besides Dogū, this period also saw the production of phallic stone objects and standing stone circles, which may have been a part of the same fertility rituals and beliefs linking to astrology.

Images of the female body as symbols of fertility are encountered in many parts of the world in the Neolithic period, presenting features unique to the regions and cultures that produced them. The preoccupation with fertility was increasingly twofold, namely the fertility of women and that of the land, as some people began cultivating their food supply and transitioning to a settled agricultural way of life.

Like the Ainu of the north, the Ryukyuans of the south shared Jōmon cultural similarities, from matrifocal social organisation, to utilisation of spiral motifs and a reverence for nature. It is thought that the orthodox religions of modern day Japan, such as marriage customs; ceremonies; architectural styles; and technological developments such as lacquerware, textiles, laminated bows, metalworking, and glass making, may have arisen through the animistic beliefs of the Shinto philosophy of this early cultural era.

Without any doubt, women took on the most important cultural roles within the arts during this period, wherever pottery, weaving and tattooing were regarded as important extensions of cultural identity, there was a central binding of these influences in local oral and material culture, through the positions that women held.

Of the southernly Ryukyuan people, Hajichi was a commonly practiced tattooing tradition before the annexation of the Ryukyu Islands during the Meiji Restoration of Japan. The tattoos vary in nature, patterns, and shapes are largely determined by region, giving each tattoo design its unique distinction.

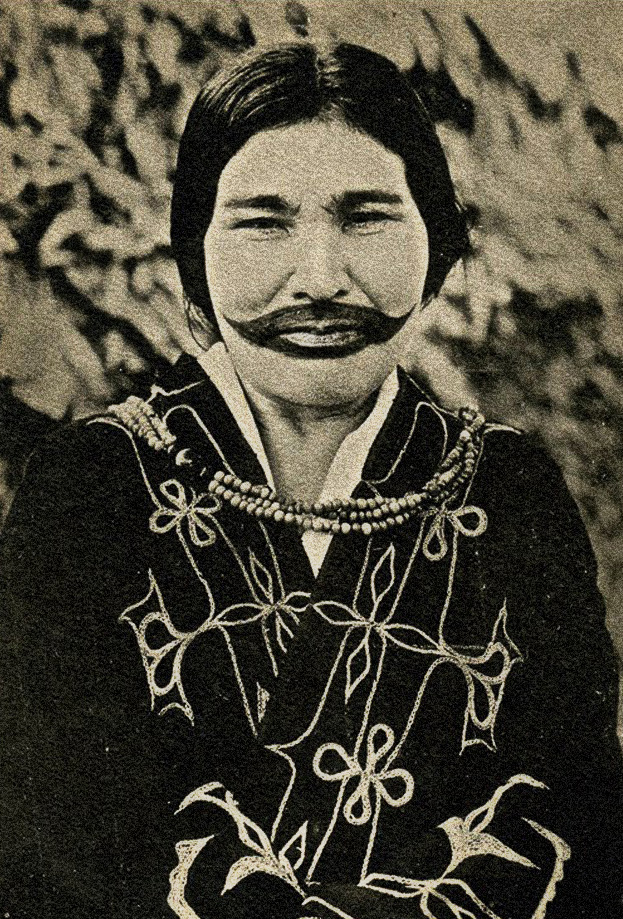

Hand tattoos were only worn by the women of the Ryukyus, and the practice was strictly preserved within female culture. For the Ainu, hand and arm tattoos were common as well as their distinctive facial tattoos.

Some researchers beleive the symbols to be markings relating to marriage, whilst other less patriarchal views relate the symbols to astrological knowledge, visions of stars and of oracle premonitions viewed at the time of birth.

The more serious significance were that these symbols were protective, to fight against sickness and disease, especially if the disease took the form of a culture with a desire to forcibly assimilate local communities and then to deny their existence.

![]()

![]()

Without any doubt, women took on the most important cultural roles within the arts during this period, wherever pottery, weaving and tattooing were regarded as important extensions of cultural identity, there was a central binding of these influences in local oral and material culture, through the positions that women held.

Of the southernly Ryukyuan people, Hajichi was a commonly practiced tattooing tradition before the annexation of the Ryukyu Islands during the Meiji Restoration of Japan. The tattoos vary in nature, patterns, and shapes are largely determined by region, giving each tattoo design its unique distinction.

Hand tattoos were only worn by the women of the Ryukyus, and the practice was strictly preserved within female culture. For the Ainu, hand and arm tattoos were common as well as their distinctive facial tattoos.

Some researchers beleive the symbols to be markings relating to marriage, whilst other less patriarchal views relate the symbols to astrological knowledge, visions of stars and of oracle premonitions viewed at the time of birth.

The more serious significance were that these symbols were protective, to fight against sickness and disease, especially if the disease took the form of a culture with a desire to forcibly assimilate local communities and then to deny their existence.

︎Okinawa and Yonaguni tattoo symbols.

︎ Ryukyuan woman with traditional hand tattoos.

︎ Ainu woman with traditional face tattoo.

Hand symbols can also refer to cosmological principles as seen within nature, where stylised butterfly bodies, shells and lunar motifs are abstracted into narratives of geometric designs.

These motifs relate to Shinto animistic beliefs, the idea of the Torii ‘the gate of prosperity’ or the temple being inside the body and accessed through the hands, and that in some extended sense, the shell is the house of the moon and our own body is the house of the soul.

In southern Japanese island traditions it is thought that these symbols relate to ideas of all objects being ‘soul-filled’ and that being in the world is a form of ‘Tamas Abya’ (soul-bathing).

These motifs relate to Shinto animistic beliefs, the idea of the Torii ‘the gate of prosperity’ or the temple being inside the body and accessed through the hands, and that in some extended sense, the shell is the house of the moon and our own body is the house of the soul.

In southern Japanese island traditions it is thought that these symbols relate to ideas of all objects being ‘soul-filled’ and that being in the world is a form of ‘Tamas Abya’ (soul-bathing).

By unearthing the matrix of cross-cultural symbolism of stone age people, the network of meanings can be traced to a common language of the goddess. It draws a picutre that is very distinct from the one that was created in the name of unifying people under the common law of a national identity. The significance of this dynamic imagery was not necessarily fixed but it was ordered, and this order coalesced within the chaos of nature itself.

According to pioneers in the fields of archaomythology like Marija Gimbutas, or scholars of Shinto animism such as Nelly Naumann, their studies show how apparent communities of ‘noble savages’ expressed a deep respect for nature that they recorded in the vocabulary of their folklore and material cultures. This vocabulary spanned borders and oceans and connected via the stars, often meeting at the same psychic conjunction; namely that wherever we are in the world, the roles we play are of great importance when sustained and rejuvanted through the cyclical image of the soul and the goddess.

Further Reading ︎

Hajichi: The Powerful Female Tattooing Tradition of the Ryukyus, article

The Ainu Oral History Project, website Ainu, New World Encyclopedia, website Ainu Postcards of Thomas Murray, website

Shinto Animism, website

The Splendor of the Middle Jomon Culture, by Ilona Bausch, pdf The Precious Potters of Ancient Japan, Apollo-Magazine article Wolrd History, Venus Figurines, website Japanese Island tattoo descriptions, website The life and work of Nelly Naumann, pdf Jomon Stone Cirlces, blog

Hajichi: The Powerful Female Tattooing Tradition of the Ryukyus, article

The Ainu Oral History Project, website Ainu, New World Encyclopedia, website Ainu Postcards of Thomas Murray, website

Shinto Animism, website

The Splendor of the Middle Jomon Culture, by Ilona Bausch, pdf The Precious Potters of Ancient Japan, Apollo-Magazine article Wolrd History, Venus Figurines, website Japanese Island tattoo descriptions, website The life and work of Nelly Naumann, pdf Jomon Stone Cirlces, blog