kapala

︎Culture, Art, Spirituality, Article

︎ Ventral Is Golden

kapala

︎Culture, Art, Spirituality, Article

︎ Ventral Is Golden

"I am food, I am food! I am the eater of food, I am the eater of food! I am the poet, I am the poet who combines the two! I am prior to the navel of immortality. He who gives me away, he alone preserves me. He who eats food, as food, I eat him.” - Taittiriya Upanishad.

The Kapala is a sacred cup that is a distinctive feature of the Shivaism tantric tradition (also found in tantric aspects of Jainism, Hinduism and Buddhism), often used ceremonially for offerings to the goddesses, the fierce deities and protectors of the central knowledge (dharma), known as Dharmapālas.

The sect known as the Kāpālika (Skull-men) is a tradition from India dating back to around the 7th Century AD, who often use the skull cup in association with the reproduction and dissolution cycles of goddesses such as Ma Durga and MahaKali.

“According to tantra, the human body is perceived as a sacred temple in which all higher forces and the whole truth about existence are present. One of those truths, fundamental to Vajrayana Buddhism, is impermanence (Skt. anitya, Tib. mitagpa). The visual representation of the transience of the human body, and hence the Buddhist idea of impermanence, is found in the iconography of the skull cup. The cup serves as a ritual vessel of many other deities in the Vajrayana pantheon, like wrathful protectors, yidams, mahasiddhas and yogis. As a ritual vessel, kapala combines the symbolism of the clay pot of Vedic sacrifices (Skt. kumbha), the Lord Buddha’s begging bowl (Skt. patra), and the sacred vase of bodhisattvas (Skt. kalasha)” (Robert Beer 1999: 263).

The cup itself is fashioned from the crown of a human usually after a Sky Burial, often hand carved with impressive bass-reliefs depicting religious scenes and adorned with semi precious stones and silver, in which an offering such as wine or dough balls act as a transubstantiation of blood and body parts that symbolise the ‘Wisdom Nectar’ (Amrita), or liquid enlightenment attained in the Celestial Palace of the Mandala.

In some mythic representations, the Kapala was derived from a fierce form of Bhikshatana (the wandering aspect of Shiva) after a dispute with Brahman about who had supreme knowledge regarding the beginning of the universe. Bhikshatana removed the fifth head of Brahman (thought to be the ego), and for this indiscretion, had to perform a vow of Kapali: to wander the world as a naked beggar with the skull attached to his hand as a constant reminder of the inability to truely overcome ego-death.

The sect known as the Kāpālika (Skull-men) is a tradition from India dating back to around the 7th Century AD, who often use the skull cup in association with the reproduction and dissolution cycles of goddesses such as Ma Durga and MahaKali.

“According to tantra, the human body is perceived as a sacred temple in which all higher forces and the whole truth about existence are present. One of those truths, fundamental to Vajrayana Buddhism, is impermanence (Skt. anitya, Tib. mitagpa). The visual representation of the transience of the human body, and hence the Buddhist idea of impermanence, is found in the iconography of the skull cup. The cup serves as a ritual vessel of many other deities in the Vajrayana pantheon, like wrathful protectors, yidams, mahasiddhas and yogis. As a ritual vessel, kapala combines the symbolism of the clay pot of Vedic sacrifices (Skt. kumbha), the Lord Buddha’s begging bowl (Skt. patra), and the sacred vase of bodhisattvas (Skt. kalasha)” (Robert Beer 1999: 263).

The cup itself is fashioned from the crown of a human usually after a Sky Burial, often hand carved with impressive bass-reliefs depicting religious scenes and adorned with semi precious stones and silver, in which an offering such as wine or dough balls act as a transubstantiation of blood and body parts that symbolise the ‘Wisdom Nectar’ (Amrita), or liquid enlightenment attained in the Celestial Palace of the Mandala.

In some mythic representations, the Kapala was derived from a fierce form of Bhikshatana (the wandering aspect of Shiva) after a dispute with Brahman about who had supreme knowledge regarding the beginning of the universe. Bhikshatana removed the fifth head of Brahman (thought to be the ego), and for this indiscretion, had to perform a vow of Kapali: to wander the world as a naked beggar with the skull attached to his hand as a constant reminder of the inability to truely overcome ego-death.

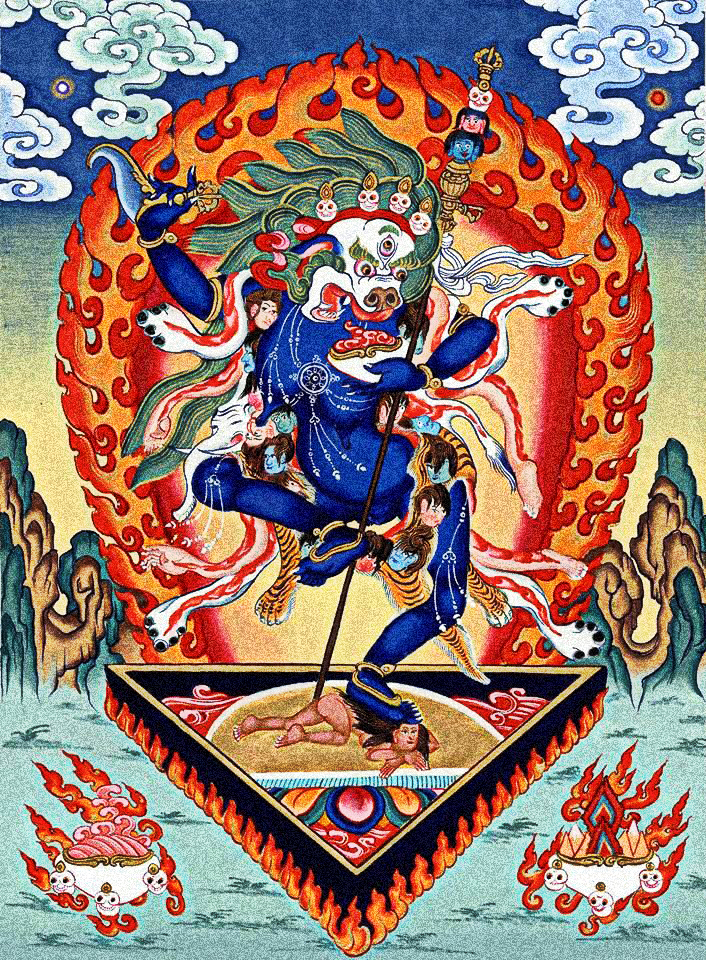

︎Mahakala (energetic aspect of Shiva (Citipati, Tib.)

︎Bhikshatana

(Shiva the wanderer, his left hand signifying Vāmācāra; the left-hand path of Tantra).

The Kapala’s origins are tied to ideas that touch upon liberation (moksha), and the powerful Shakti aspect (divine feminine energy) of Shiva. The Buddhist notion of death and imperanence are also entwined with the idea of perfect awareness. The Tibetan Book of the Dead (Bardo Thodol) is a tantric text for guiding the spirit through to the next realm via the use of speech or song, and states that; “the nature of mind is empty and without foundation. One’s own mind is insubstantial, like an empty sky. Look at your own mind to see whether it is like that or not. Divorced from views which constructedly determine emptiness, be certain that pristine cognition, naturally originating, is primordially radiant – just like the nucleus of the sun, which is itself naturally originating. Look at your own mind to see whether it is like that or not! Be certain that this awareness, which is pristine cognition, is uninterrupted, like the coursing central torrent of a river which flows unceasingly.”

As death is so intimately woven with the process of life in ancient philosophical traditions, there has also been some basis in biologcial studies that suggest that as an embryo develops, the initial state of the hands go through a process of molecular regression and decay which shapes the fingers from their initial stage of being ‘webbed’. The suggestion is that humanity is literally sculpted by the presence of death in order to come into existence, once again conjuring the symbolism of Bhikshatana.

This notion combines the philosophical aspects prevalent in most eastern cultures, namely that life and death are products of the same process and give rise to eternal change and impermanence (anitya).

The union of these temporary phenomena within emptiness is the state of Dharma-Kāya (truth-body) of Perfect Enlightenment.

This is embodied in the religious iconography of Buddhism and Hinduism across Tibet, India and China and in Hindusim, where each deity transforms into an avatar - a kind of psychological reaction to the situation they find themselves in, often presenting an opportunity for the avatar to transcend the situation through some kind of philosophical sacrifice or magical comprehension of nature and the nature of empitness.

“Our past thinking has determined our present status, and our present thinking will determine our future status; for we are what we think.” - W.Y. Evans-Wentz on the Bardo Thodol.

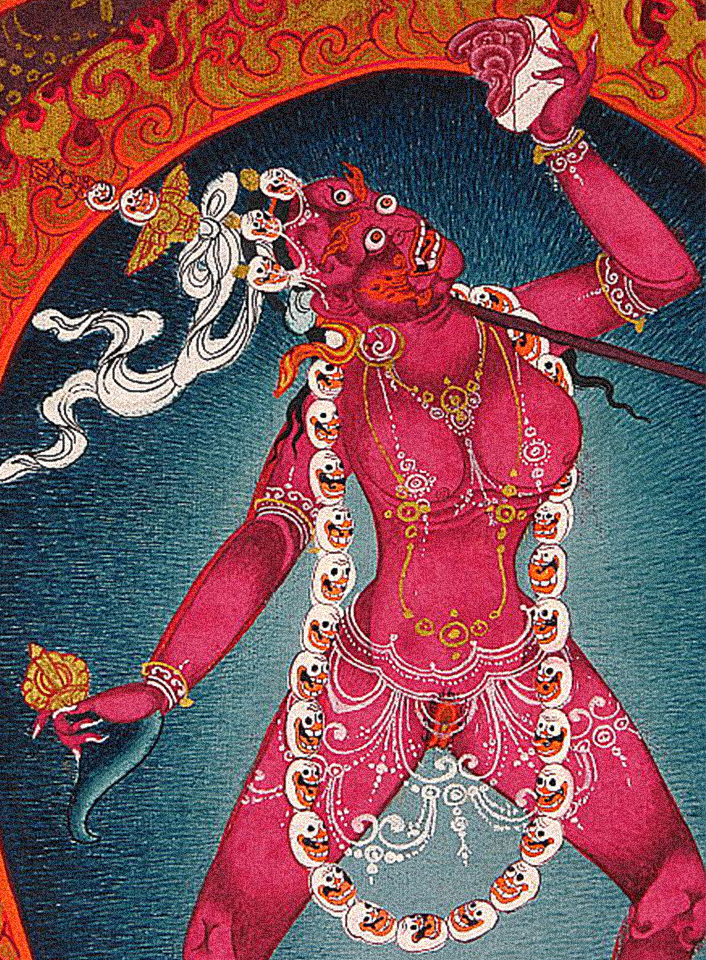

The nature of the feminine, particulary in Tibetan Buddhism, is also evoked by the iconography of the Dakini, which is closely related to the Kapala traditions. The word Dakini is translated as ‘women who dance in the sky’ or interpreted as ‘women who revel in the freedom of emptiness’.

Their essential trait is dynamism, often depicted as dancing brilliant red bodies, representing inferno, self-transformation and enlightenment. The skull cup, which they often carry, has been suggested as being filled with menstrual blood, a Wisdom Elixir (amrita) as afore mentioned, that cleanses and self regulates the female body, coinciding with the rhythmic cycles of nature herself.

In the spirit of equilibrium, the Dakini and the Kapala do not represent the kind of one sidedness associated with western monotheism. The motif of the Tantric shaft (Khatvanga) of the Dakini, denotes masculinity too, as both masculine and feminine can only be characterised by their relationship to one another. If the hardness of wood is evoked by the softness of skin, masculinity is contextualised by the presence of the feminine, never the two are fully separated.

Consequently, as the Kapala signifies symbolic death, it can then be apprehended as a catalyst for life, in the same way the embryo undergoes its mini molecular death as it enters into the world.

Their essential trait is dynamism, often depicted as dancing brilliant red bodies, representing inferno, self-transformation and enlightenment. The skull cup, which they often carry, has been suggested as being filled with menstrual blood, a Wisdom Elixir (amrita) as afore mentioned, that cleanses and self regulates the female body, coinciding with the rhythmic cycles of nature herself.

In the spirit of equilibrium, the Dakini and the Kapala do not represent the kind of one sidedness associated with western monotheism. The motif of the Tantric shaft (Khatvanga) of the Dakini, denotes masculinity too, as both masculine and feminine can only be characterised by their relationship to one another. If the hardness of wood is evoked by the softness of skin, masculinity is contextualised by the presence of the feminine, never the two are fully separated.

Consequently, as the Kapala signifies symbolic death, it can then be apprehended as a catalyst for life, in the same way the embryo undergoes its mini molecular death as it enters into the world.

“O, child of noble family, be not daunted, nor terrified, nor in awe.

This is the radiance of your own nature. Recognise it.” - W.Y. Evans-Wentz (Bardo Thodol).

The highest teachings of emptiness are in the ‘Prajnaparamita Sutras’ or Heart Sutras, often associated with the Dakinis, Yoginis, Naginis and Apsaras (dancers) of the tantric traditions, as they are tasked with being guardians of this sacred knowledge at the centre of Buddhist thought. The dance of the Dakini, like the contents of the kapala, ripple across the surface of reality as the highest form of emptiness.

It is said that anyone who can spontaneously achieve Bodhicitta (the union of empitness and compassion; meaning the enlightened-body), can comprehend the ‘inherent non-dual consciousness’ in which male and female principles are represented as one. This concept is contained within the contents of the kapala itself and are suggestive of the psychology most closely related to the act of making offerings.

The Dakini’s are often thought of as messengers who can reveal hidden treasures called Terma, who can guide a practitioner towards ‘sambhogakaya’ (the bliss-body); one of the three bodies or fruits of the ‘contemplative life’.

This complex symbology of the Kapala has been used to describe the natural cycles of the body for thousands of years, and has since been used analogously with discoveries made on the subatomic level of reality in relation to the wave functions of quantum reality (the most popular symbolism in this context being the Shiva Nataraja statue outside the Large Hardon Collider at CERN.)

It is said that anyone who can spontaneously achieve Bodhicitta (the union of empitness and compassion; meaning the enlightened-body), can comprehend the ‘inherent non-dual consciousness’ in which male and female principles are represented as one. This concept is contained within the contents of the kapala itself and are suggestive of the psychology most closely related to the act of making offerings.

The Dakini’s are often thought of as messengers who can reveal hidden treasures called Terma, who can guide a practitioner towards ‘sambhogakaya’ (the bliss-body); one of the three bodies or fruits of the ‘contemplative life’.

This complex symbology of the Kapala has been used to describe the natural cycles of the body for thousands of years, and has since been used analogously with discoveries made on the subatomic level of reality in relation to the wave functions of quantum reality (the most popular symbolism in this context being the Shiva Nataraja statue outside the Large Hardon Collider at CERN.)

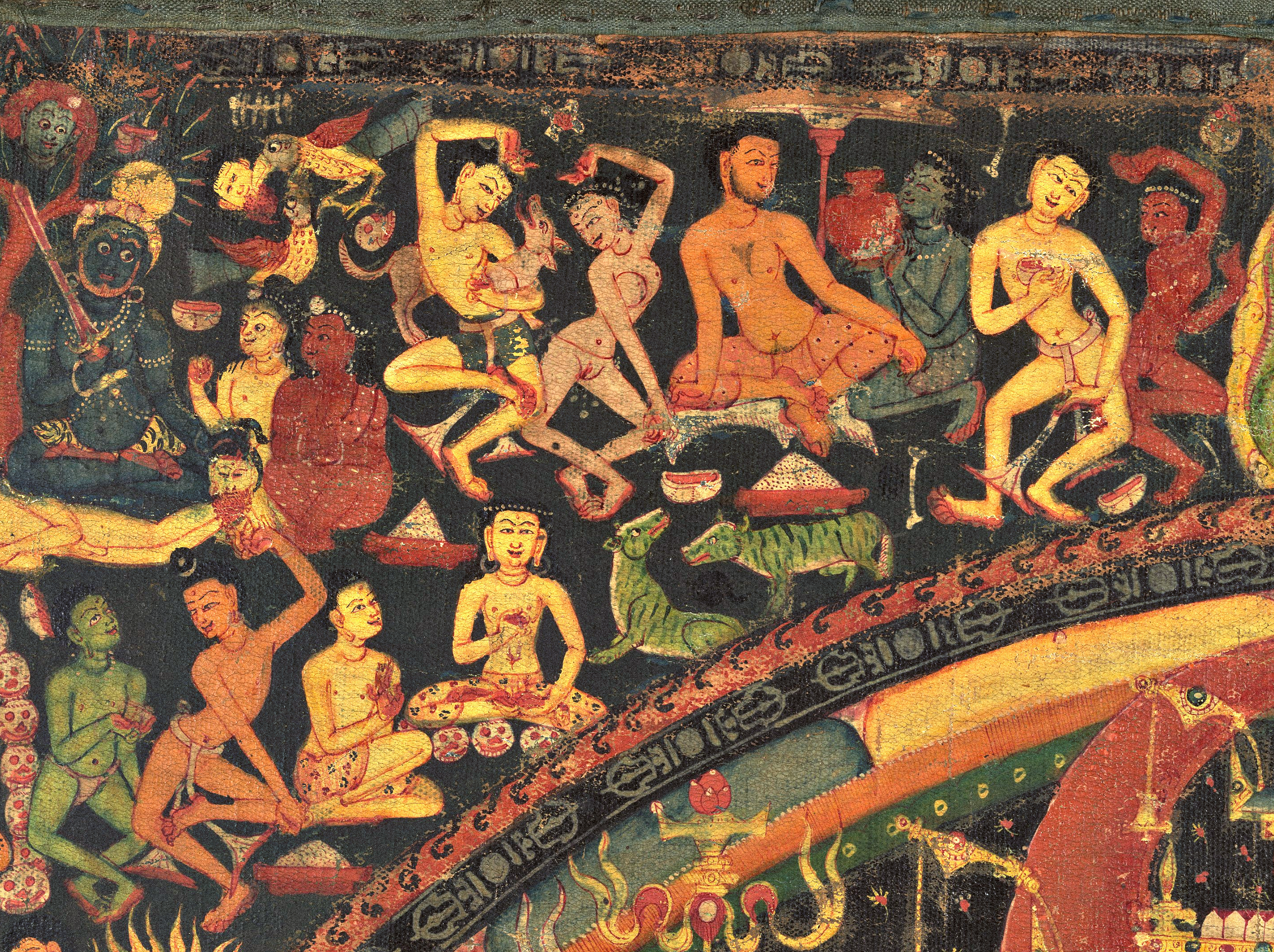

︎Close up of Kapala details in the Chakrasamvara Mandala

(The Binding of the Wheels). Nepal, 8th Century.

(The Binding of the Wheels). Nepal, 8th Century.

Further Reading ︎

Dance of the Yogini: Images of Aggression in Tantric Buddhism, by Nitin Kumar

Tribal art, Asia:Kapala Skull cups

Taittiriya Upanishad