rithika merchant

︎Artist, Painting, Spirituality

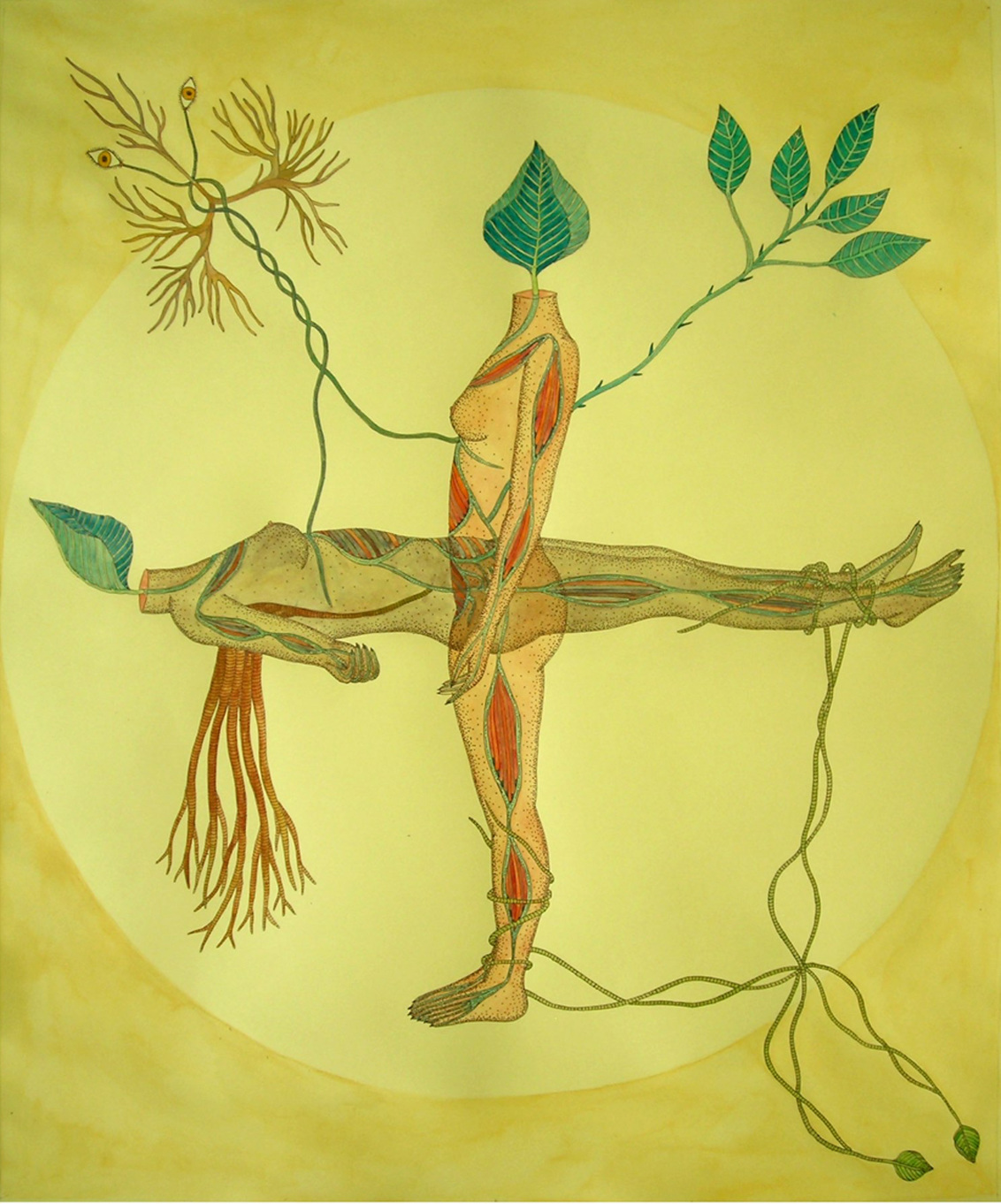

︎ Ventral Is Golden

rithika merchant

︎Artist, Painting, Spirituality

︎ Ventral Is Golden

︎ Ventral Is Golden

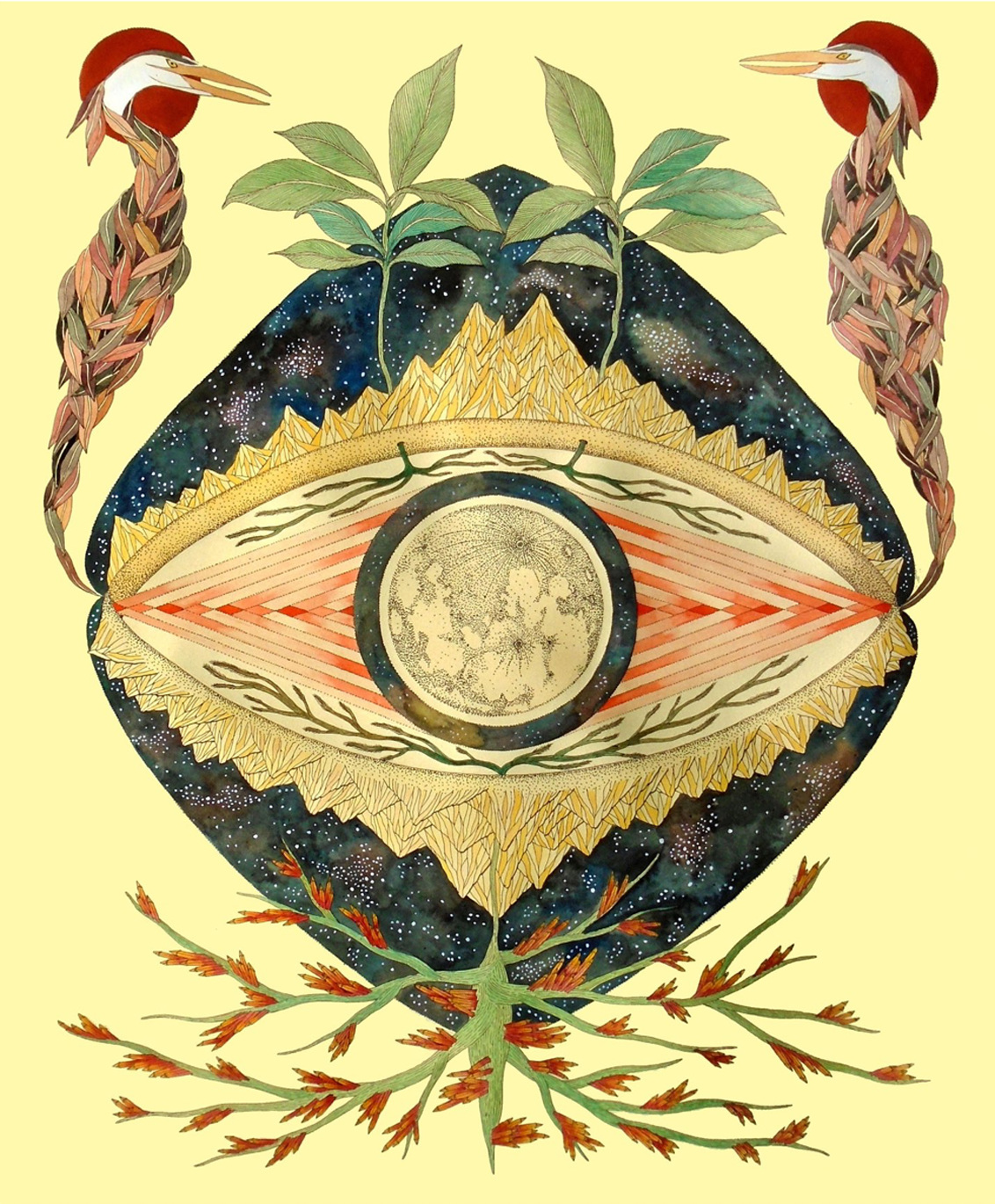

“The Goddess is immanent rather than transcendent and therefore physically manifest.“ - Marija Gimbutas.

In her book 'The Chalice and the Blade', Riane Eisler, by reviewing social history from the Palaeolithic through to its patriarchal transition, discusses how the religious symbolism altered social structure from the feminine partnership motif of the chalice to the male dominator motif of the blade. Through these symbols, Eisler explores the psychological structures inherent within them, and states that "The way we interpret ancient symbols and myths still plays an important part in how we shape both our present and our future. At the same time that some of our religious and political leaders would have us believe a nuclear Armageddon may actually be the will of God, we are seeing a vast reaffirmation of the desire for life, not death, in an accelerated, and indeed unprecedented, movement to restore ancient myths and symbols to their original gylanic meaning."

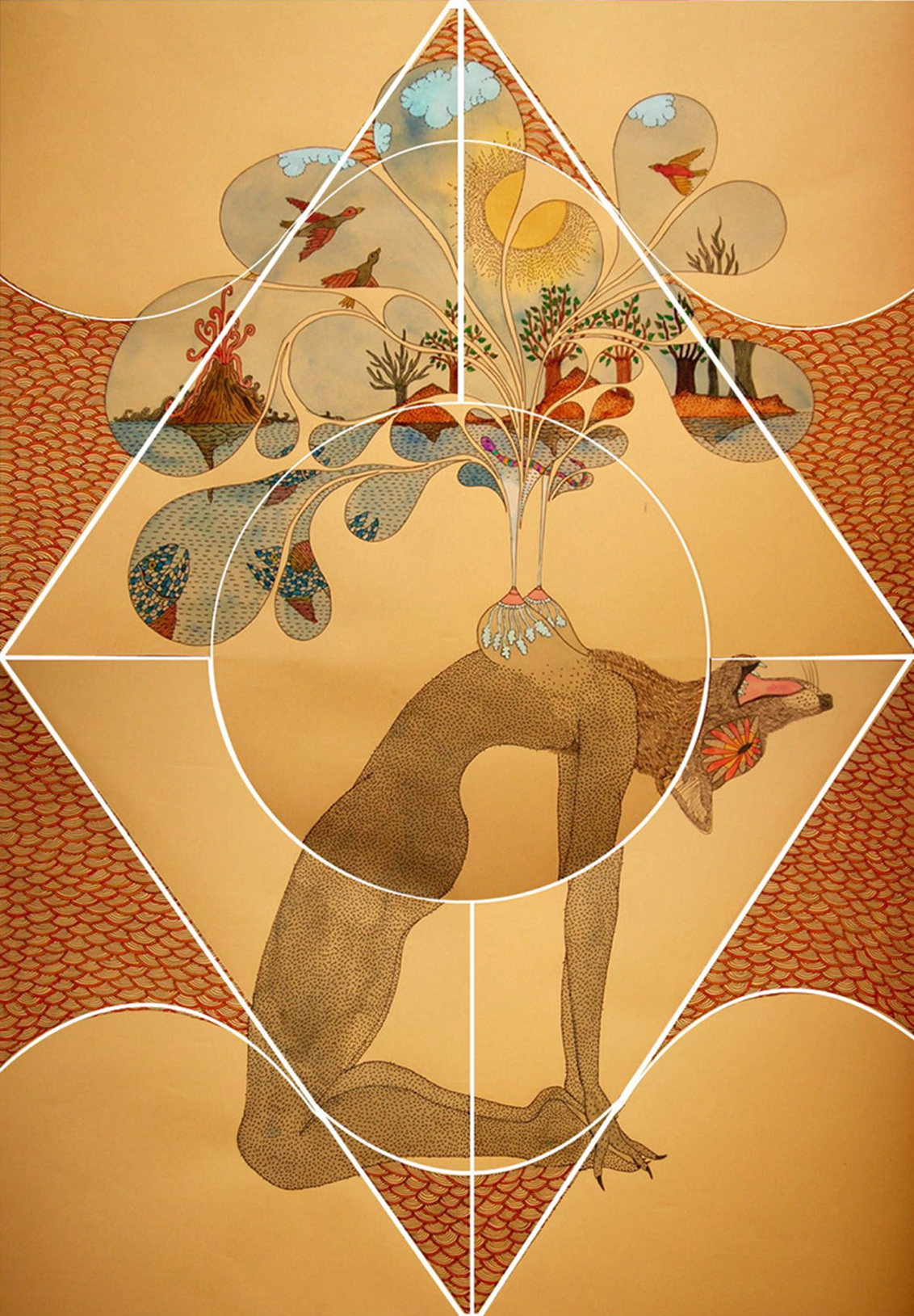

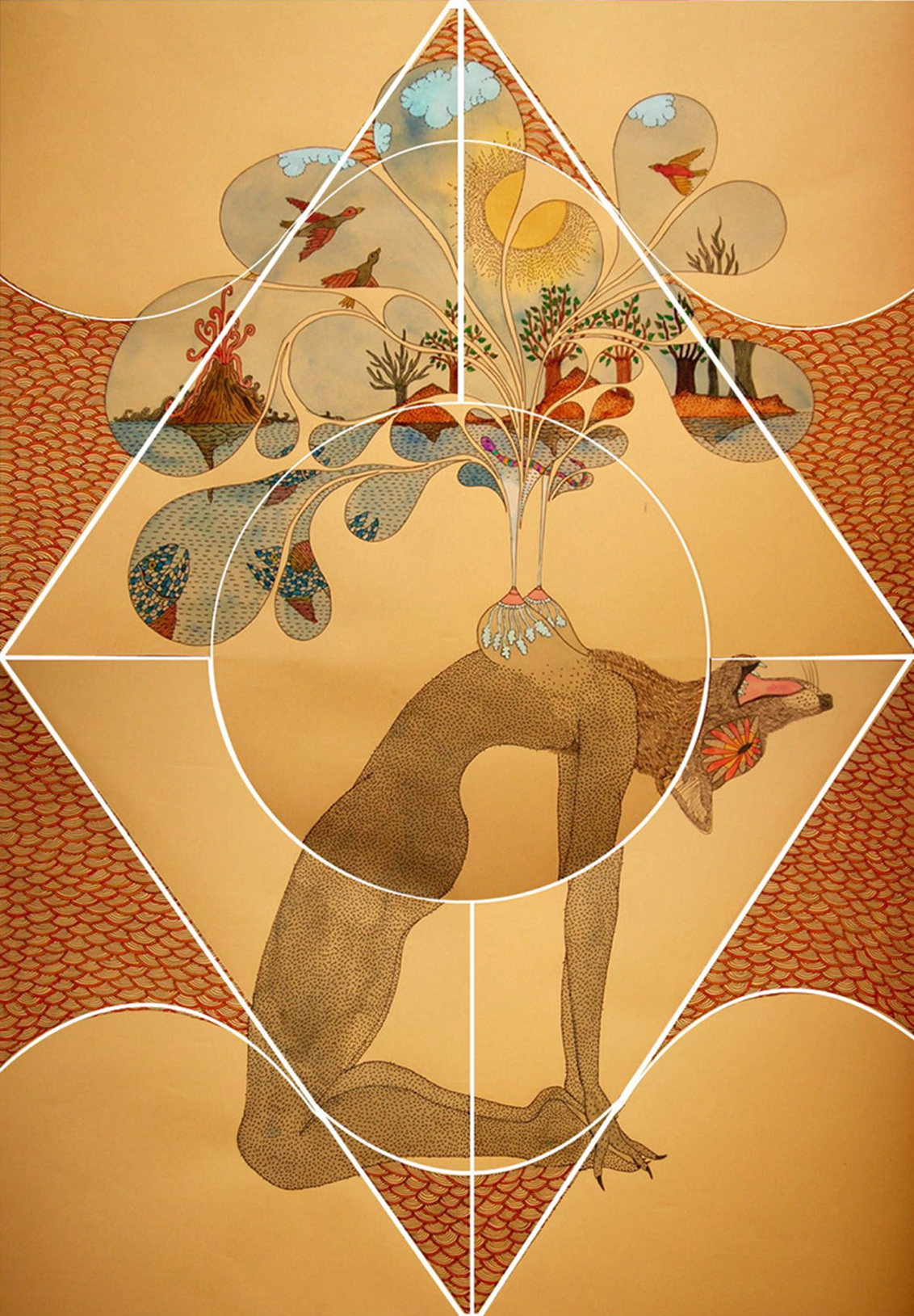

The sentiments expounded by Eisler in her book ‘The Chalice and the Blade’, are echoed in the works of Rithika Merchant, an Indian artist currently residing in Barcelona, who’s paintings draws heavily upon a substantial visual vocabulary that emanates from deep within the akashic archive of collective historical memory.

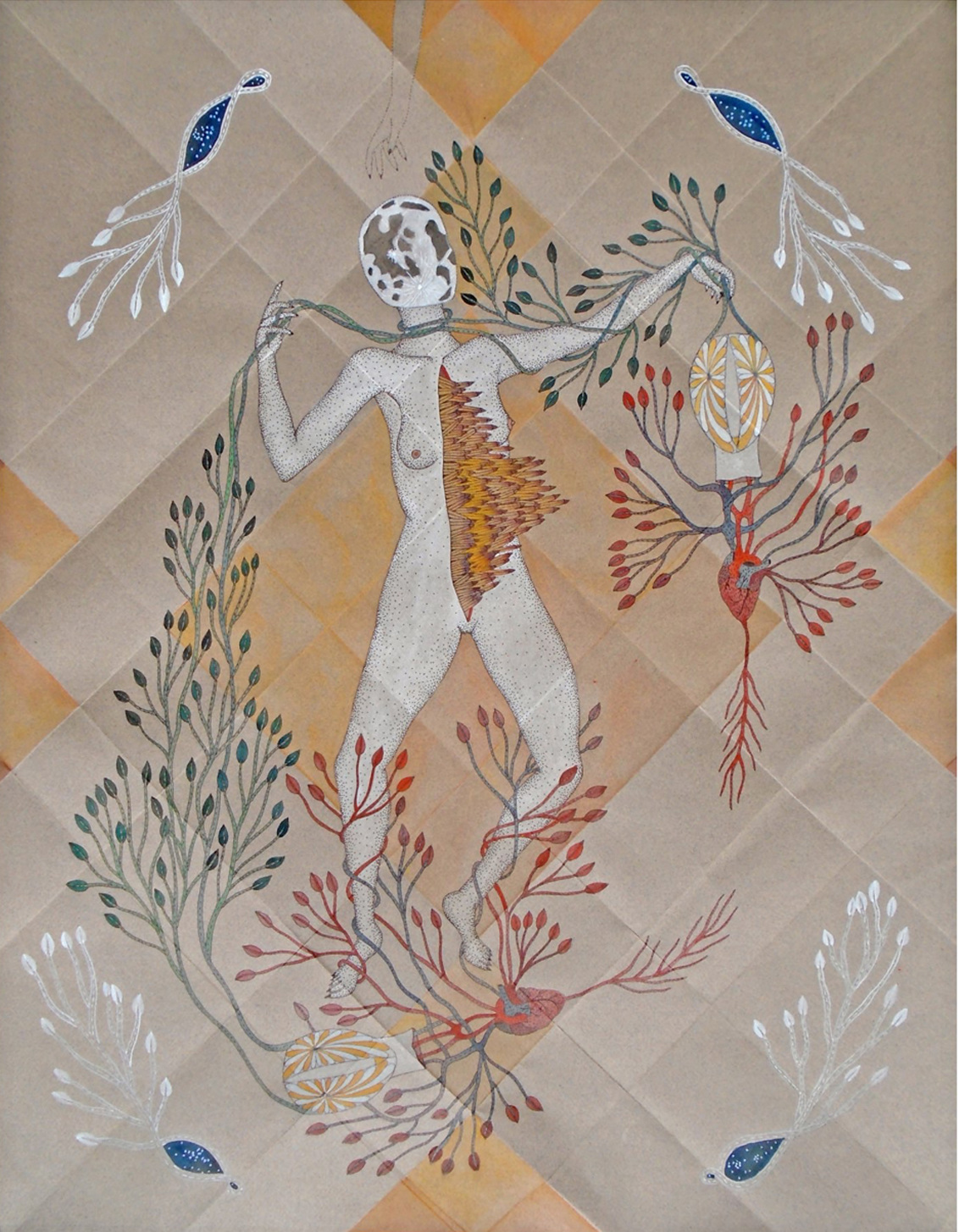

Merchant's work, instead of pertaining solely to the conventional aspects of received history through written traditions, attempts to democratise the impact of mythic symobls through highlighting the commonality and personality embedded within them.

Merchant suggests that "the combination of having grown up in India, studied in the U.S.A, travelling extensively and finally settling in Europe, is the reason for my interest in the links between cultures. I've been lucky enough to have explored different cultures to observe them. Both Europe and India have such a mixture of different traditions, it has helped me see parallel histories everywhere. The history of myth and traditions shows links between cultures that often isn't highlighted in classical history."

![]()

Merchant's work, instead of pertaining solely to the conventional aspects of received history through written traditions, attempts to democratise the impact of mythic symobls through highlighting the commonality and personality embedded within them.

Merchant suggests that "the combination of having grown up in India, studied in the U.S.A, travelling extensively and finally settling in Europe, is the reason for my interest in the links between cultures. I've been lucky enough to have explored different cultures to observe them. Both Europe and India have such a mixture of different traditions, it has helped me see parallel histories everywhere. The history of myth and traditions shows links between cultures that often isn't highlighted in classical history."

The symbols that Eisler explores in her book are not necessarily related to gender, but more energetically intertwined with characteristics of male and female that have been adopted and distorted by current psychological trappings of Western civilisation and the shifting sense-ratios brought about by new technologies. The characteristics of Eisler's 'chalice' and 'blade' are perhaps more akin to the ancient Chinese dualism of yin-yang (broken and unbroken lines of the I Ching (Book of Changes) that signify strong and weak, creative and receptive, and so on) that were once seen as a constant interplay of opposites, creating new dynamic perspectives on how natural phenomena emerge and how to respond accordingly depending on the kind of characteristics required in the organisation of those energies.

“I use symbols found in nature a lot - as I think that is something that all cultures have in common.“

It is for this reason that Eisler talks about partnership societies as ‘gylanic’, as the overthrowing of Patriarchy with Matriarchy is simply substituting dominance with dominance. There are thematic overtones of collaboration and assimilation within Merchant's work also, that allude to this partnership mentality. As Merchant explains, "I definitely do not try to make culture specific reproductions of myths. Nowadays I have been trying to make my symbolism as non-specific and as universal as possible. I use symbols found in nature a lot - as I think that is something that all cultures have in common. A lot of the time people see my work and immediately want to know the story behind it. I encourage them to first look at the title of the piece for hints and try to find significance in the symbolism within the work. Each piece tells many stories and sometimes the best ones are not what I have thought about whilst creating the work."

Given that the cult of information is a common theme of our modern civilisation, asking what art inherently is, what something 'means', can be somewhat misguided. Nonetheless, digital technology has had implicit affects on almost everyhting from our most common rituals to our most cosmic revelations, and the question of what something means can in someways become the seed of situating an old idea within an overly complexified matrix of unnecessary connections. Merchant goes on to explain that "contemporary art has a function of culture mapping. As images and stories travel far and wide, sometimes within minutes, our age has become one of over saturation. For art and narrative to resonate, they must speak honestly and emotionally. The response to the art as well as it’s place within the broader cultural movement of the time, is both enhanced by how fast things move on the internet and hindered by how soon they can be forgotten."

![]()

“The response to the art as well as it’s place within the broader cultural movement of the time, is both enhanced by how fast things move on the internet and hindered by how soon they can be forgotten.”

For Eisler, the widely held notion that technology is causing our global problems is a common misconception as she writes, "Indeed, the story of human culture is to a large extent the story of human technology. It is the story not only of the fashioning of material tools but also of our most important and unique non-material tools: the mental tools of language and imagery, of human-made words, symbols, and pictures... technology is itself part of the evolutionary impulse, the striving for the expansion of our potential as human beings within both culture and nature. Once we look at technology from the new perspective provided by the gender-holistic analysis of our past and present, it is clear that the problem is not now nor has it ever been simply that of technology. The same technological base can produce very different types of tools: tools to kill and oppress other humans or tools to free our hands and minds from dehumanising drudgery. The problem is that in dominator societies, where "masculinity" is identified with conquest and domination, every new technological breakthrough is basically seen as a tool for more effective oppression and domination. That is, what led to the nineteenth century's exploitation of women, children, and men in sweat shops and mines and the twentieth century factories of dehumanising assembly lines where workers became cogs in industrial machines was not the invention of machines. Rather, it was the use to which that mechanisation was put in a dominator system. Similarly, the use of modern technologies to devise ever more effective and costly weapons is not a requirement of modern technology. It is, however, a requirement of dominator systems, where throughout recorded history the highest priority has been given to technologies fashioned not to sustain and enhance life, but technologies to dominate and destroy."

Taking in as much of the historical and cultural information as we can, we begin to understand that the way we interact with all phenomena, whether digital, political, mythological and so on, often dictates the form of the resulting application with which we use to navigate these topics societally, often times with the hidden compulsion to see these phenomena as capsules of informationin which to extract as value.

In essence what this means is the cultural equipment we use to deal with problems have their own psychological directives, much in the same sense that the observer changes the behaviour of particles in quantum physics, the metaphors of reality change with every technological advance.

What Rithika Merchant's work encapsulates is an echo of mythic fragments where each piece reflects back our position in an increasingly digital construct of the world around us. Merchant draws parallels between ideologies of weaponisation of the West and the ancient Indian Visha Kanya, the Poison Girls, for example, who's sexuality became their greatest weapon against an oppresive regime.

"In the past, art and stories were often a way to make sense of natural phenomena and psychological events. In modern times and for the foreseeable future, science gives us a complete explanation for most things. However, it places humans as part of a greater scheme rather than the centre of our own narrative. As much as science gives a more accurate description of humanity, it takes away the spiritual power given to every human to understand their own destiny. I try to bring humanity back to the centre of concern."

In essence what this means is the cultural equipment we use to deal with problems have their own psychological directives, much in the same sense that the observer changes the behaviour of particles in quantum physics, the metaphors of reality change with every technological advance.

What Rithika Merchant's work encapsulates is an echo of mythic fragments where each piece reflects back our position in an increasingly digital construct of the world around us. Merchant draws parallels between ideologies of weaponisation of the West and the ancient Indian Visha Kanya, the Poison Girls, for example, who's sexuality became their greatest weapon against an oppresive regime.

"In the past, art and stories were often a way to make sense of natural phenomena and psychological events. In modern times and for the foreseeable future, science gives us a complete explanation for most things. However, it places humans as part of a greater scheme rather than the centre of our own narrative. As much as science gives a more accurate description of humanity, it takes away the spiritual power given to every human to understand their own destiny. I try to bring humanity back to the centre of concern."

“In the past, art and stories were often a way to make sense of natural phenomena and psychological events. In modern times and for the foreseeable future, science gives us a complete explanation for most things.“

Further Reading ︎

Rithika Merchant, website

Riane Eisler, The Chalice and the Blade, pdf review

The Chalice and the Blade, wiki