shipibo-conibo

︎Article, Painting, Sculpture, Textile

︎ Ventral Is Golden

shipibo-conibo

︎Article, Painting, Sculpture, Textile

︎ Ventral Is Golden

"Art is the imposing of a pattern on experience, and our aesthetic enjoyment is recognition of that pattern.” - Alfred North Whitehead.

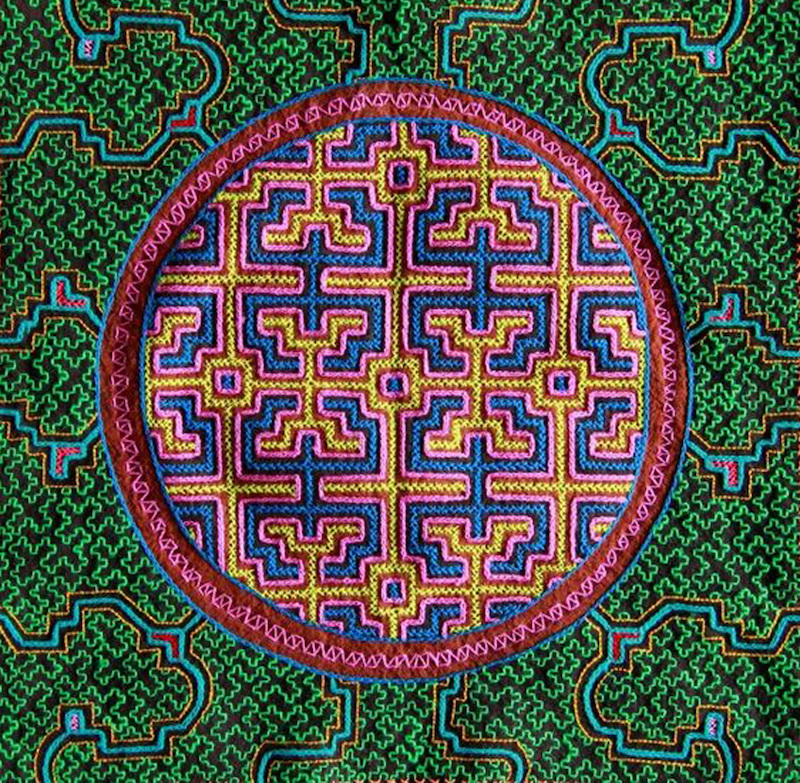

There are approximately twenty three thousand ‘jonikon’ (“true people”) settled in about 130 villages along the Ucayali River and its main tributaries. In the past, they considered themselves as three different ethnic groups: Shipibo (the monkeys), Conibo (the eels), and Xetebo (the vultures). However, presently these three groups constitute almost a single unit that names themselves Shipibo. Noted for their skills in pottery and weaving, their artistic vision is often manifest through their ancestral, collective, ritual use of Ayahuasca, and their culture shows great vitality, in spite of their long and extensive contact with the mestizo society (Valenzuela, 1997).

The Shipibo-Conibo, sometimes collectively known as ‘Weavers of Music’, generate recursive patterns, or pathways, in their tapestries and pottery that create a concrescence between sound and vision. The patterns are considered by some anthropologists as a language, either a coded symbology of medicinal rites or as a means of navigating the river structures of the Amazon jungle. The audible aspect is practised through the Icaros - a song, melody or glossolalic chant that is sung by the Ayahuasquero (shaman) to aid the practitioner in their travels through the ancient dimensions of the Ayahuasca hallucination.

It has been suggested that the word for icaro in the native Quechua language is the verb ‘ikaray’ which means ‘to blow smoke’ and amongst the Shipibo-Conibo people these magic melodies are known as taquina, masha, and cusho, which mean “to work by blowing”. (Arévalo as cited in Luna, 1986).

Every Ayahuasquero has their own icaros, based on their own experience of the plant, derived from the visions or dreams induced directly from nature. The chant consists of very simple words that allude to plants and animals of the environment, in an attempt to evoke their spirit. This act of chanting can ‘charge’ an object and influence a desired outcome. For example, the blowing of tobacco smoke by the shaman, over an area of the body can have restorative effects.

“It is hard for us to glimpse the whole pattern of the whole of what is happening. And yet, we can sense that there is a purpose, and there is a pattern.” - Terence McKenna.

Produced almost exclusively by the tribe’s women, the tribal motifs characterise their interconnectedness with nature. This is most notable by means of their production. As each motif portrays a fractal composition, the belief is that these patterns are not created, but revealed. In this sense the creative vision is shared across the entire community, with the woman who often started the artwork rarely being the person to complete it.

This method of creating art is enough to extend the mental functions and consciously evoke the ‘out of body experience’. By weaving multi-disciplined approahces with the intention of creating an outcome that is already in many senses ‘lived-in’, the geomtric designs, the icaros, the breathing, all create a perspective that is seen through the ears, or a music that is heard through the eyes, having being itself evoked from the enivronment in which it was imagined.

This method of creating art is enough to extend the mental functions and consciously evoke the ‘out of body experience’. By weaving multi-disciplined approahces with the intention of creating an outcome that is already in many senses ‘lived-in’, the geomtric designs, the icaros, the breathing, all create a perspective that is seen through the ears, or a music that is heard through the eyes, having being itself evoked from the enivronment in which it was imagined.

In Western cultures and medicine, ayahuasca, (as well as the Icaros) is too often given the perjorative label of ‘primitive’, despite the historical relevance, botanical knowledge and the cultural practices dating back thousands of years.

Considered a highly evolved folk pharmacology, Ayahuasca is active in humans only through a binary mixture of plant species. This presents a mystery to anthropologists as to how, in such a densely diversified environment as the Amazon rainforest, the plant’s healing properties were able to be initially discovered.

It is a strongly held belief, across many indigenous cultures, that the emergent patterns and motifs contained within the Ayahuasca vision are the underlying connective geometries that unite nature, mind and body. This archetypal symbolism (found across all continents and encoded within the mythology of religions) has demonstrated a living knowledge of molecular and biological processes, often later forming a basis for modern medicinal research to generating insights into the structure of DNA itself.

When asked how they attained this sacred knowledge, indigenous shamans often reply, “The plants told us”.

As well as having the ability to treat psychological and physiological illnesses, Ayahuasca has also been used for centuries by experienced, indigenous shamans as a way of communicating with ancestral spirits. As early as 1905, the active alkaloid present in the plant was given the name ‘telepathine’ because of it’s noted ability to affect group mind and open dialogue directly with the environment.

The work of the Shipibo-Conibo tribe (and other notable artists who articulate this phenomena such as Pablo Amaringo) should truly be labelled in their own right as ‘visionary’.

![]()

Considered a highly evolved folk pharmacology, Ayahuasca is active in humans only through a binary mixture of plant species. This presents a mystery to anthropologists as to how, in such a densely diversified environment as the Amazon rainforest, the plant’s healing properties were able to be initially discovered.

It is a strongly held belief, across many indigenous cultures, that the emergent patterns and motifs contained within the Ayahuasca vision are the underlying connective geometries that unite nature, mind and body. This archetypal symbolism (found across all continents and encoded within the mythology of religions) has demonstrated a living knowledge of molecular and biological processes, often later forming a basis for modern medicinal research to generating insights into the structure of DNA itself.

When asked how they attained this sacred knowledge, indigenous shamans often reply, “The plants told us”.

As well as having the ability to treat psychological and physiological illnesses, Ayahuasca has also been used for centuries by experienced, indigenous shamans as a way of communicating with ancestral spirits. As early as 1905, the active alkaloid present in the plant was given the name ‘telepathine’ because of it’s noted ability to affect group mind and open dialogue directly with the environment.

The work of the Shipibo-Conibo tribe (and other notable artists who articulate this phenomena such as Pablo Amaringo) should truly be labelled in their own right as ‘visionary’.

︎The Song The Plants Taught Us, 1991.

Notable anthropologist and researcher of the Ayahuasca tea ceremonies, Dr Luis Eduardo Luna, documented one of the ceremonies in the Peruvian Andes in his field recording ‘The Songs the Plants Taught Us’, which gives us insight into the floating, transcendental and recursive rhythms evoked by the spirit world of the ayahuasca guide.

Further Reading ︎

Ayahuasca Visions (Book) - Pablo Amaringo & Dr. Luis Luna

Ayahuasca Visions (Article) - Dennis McKenna on Reality Sandwich

The ‘icaro’ or Shamanic Song - Dr Jacques Mabit

Further Reading ︎

Ayahuasca Visions (Book) - Pablo Amaringo & Dr. Luis Luna

Ayahuasca Visions (Article) - Dennis McKenna on Reality Sandwich

The ‘icaro’ or Shamanic Song - Dr Jacques Mabit