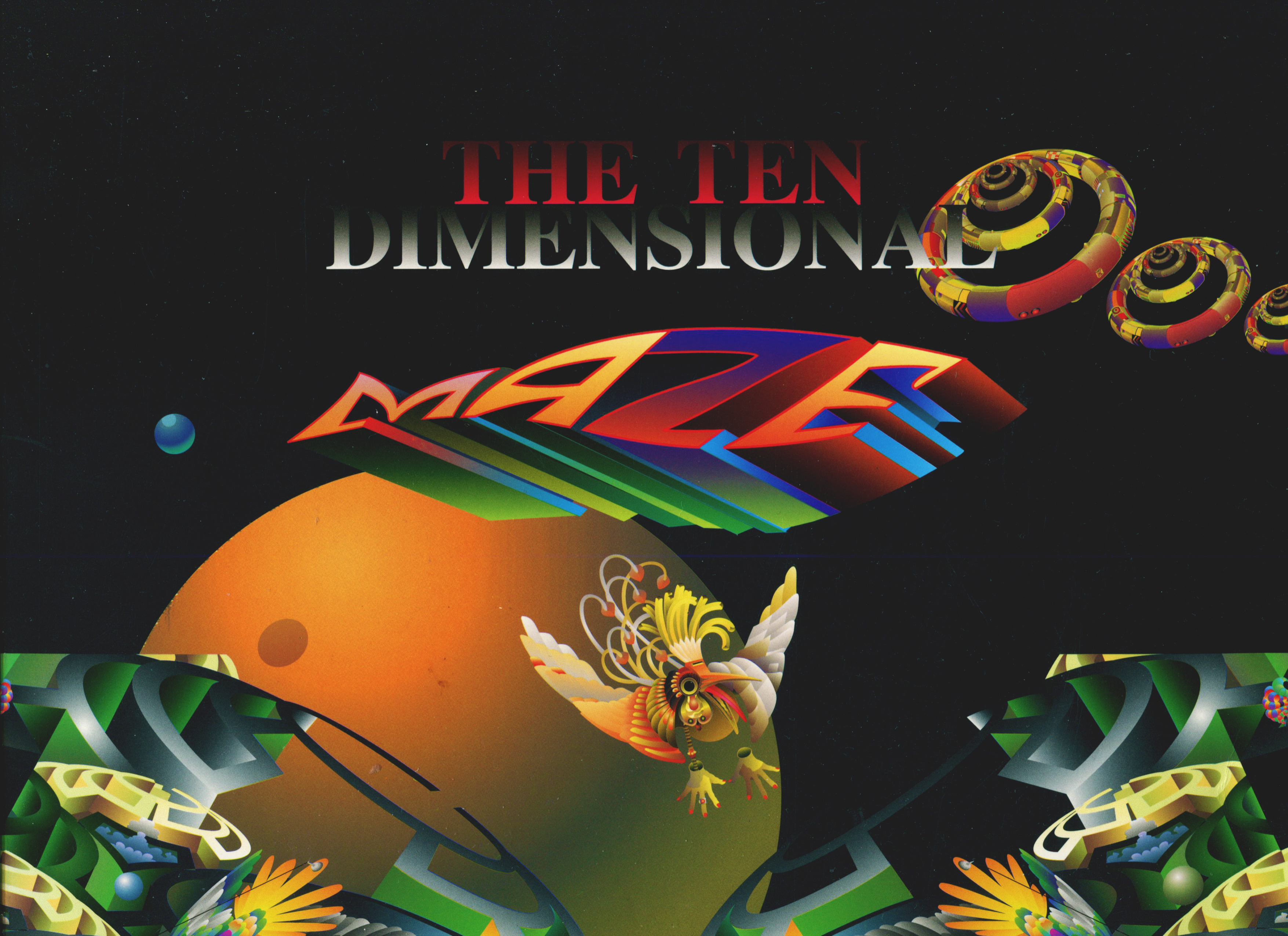

the ten dimensional maze

︎Book, Graphic Design, Digital Illustration, Article

︎ Ventral Is Golden

the ten dimensional maze

︎Book, Graphic Design, Digital Illustration, Article

︎ Ventral Is Golden

︎ Ventral Is Golden

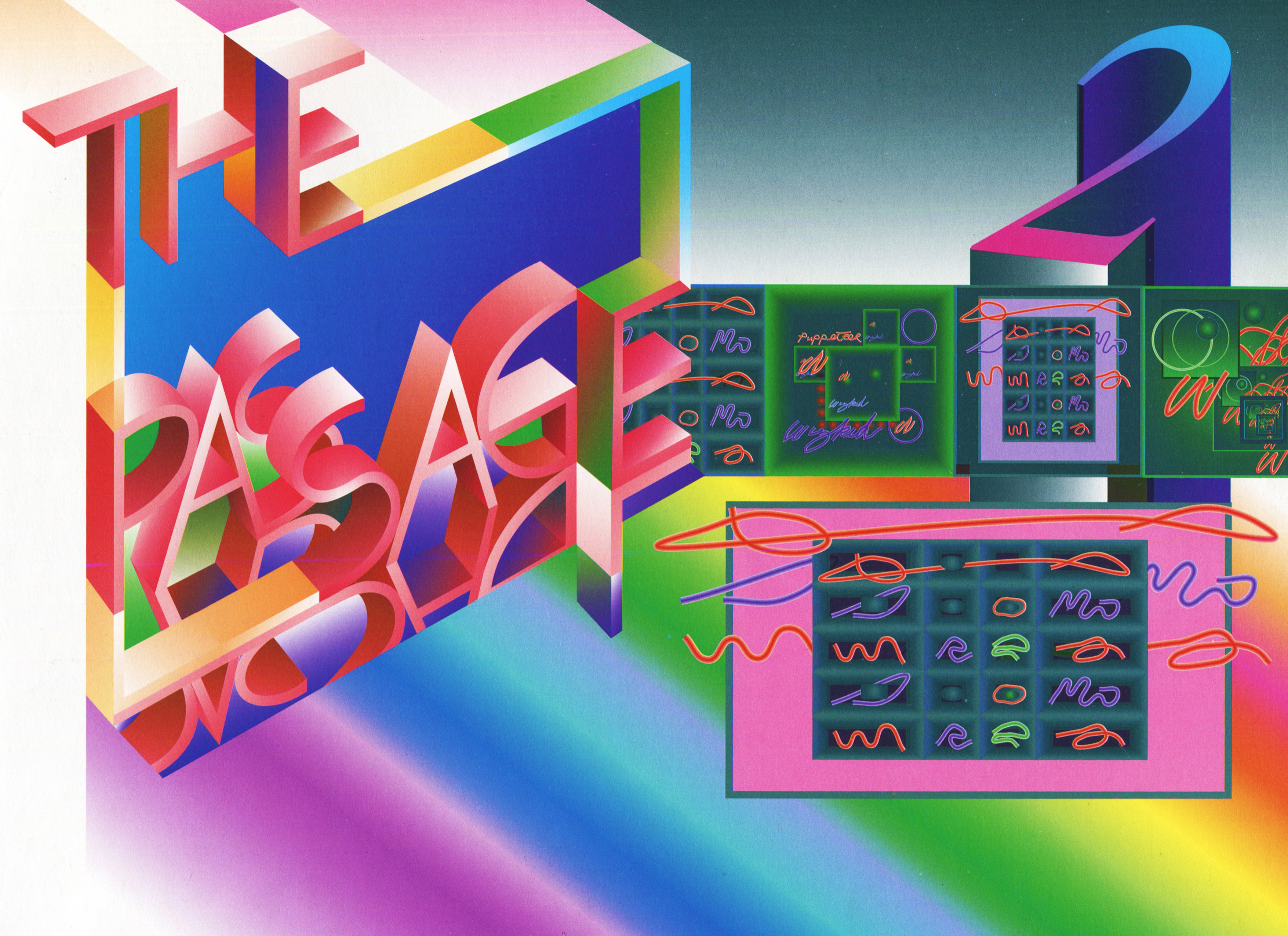

“Once the puppet’s remains had been gathered, they felt free to consider their surroundings” - The Ten Dimensional Maze.

Like all visionary ideas, by their very nature, they run the risk of being simply wrong, but because what they seek to do is so glorious, they to some degree fall upon the eye of the beholder to assess, and it is for this that they are wholly worth communicating. ‘The Ten Dimensional Maze: A Digital Fantasy in the Spirit of Lewis Carroll’ is one of these ideas.

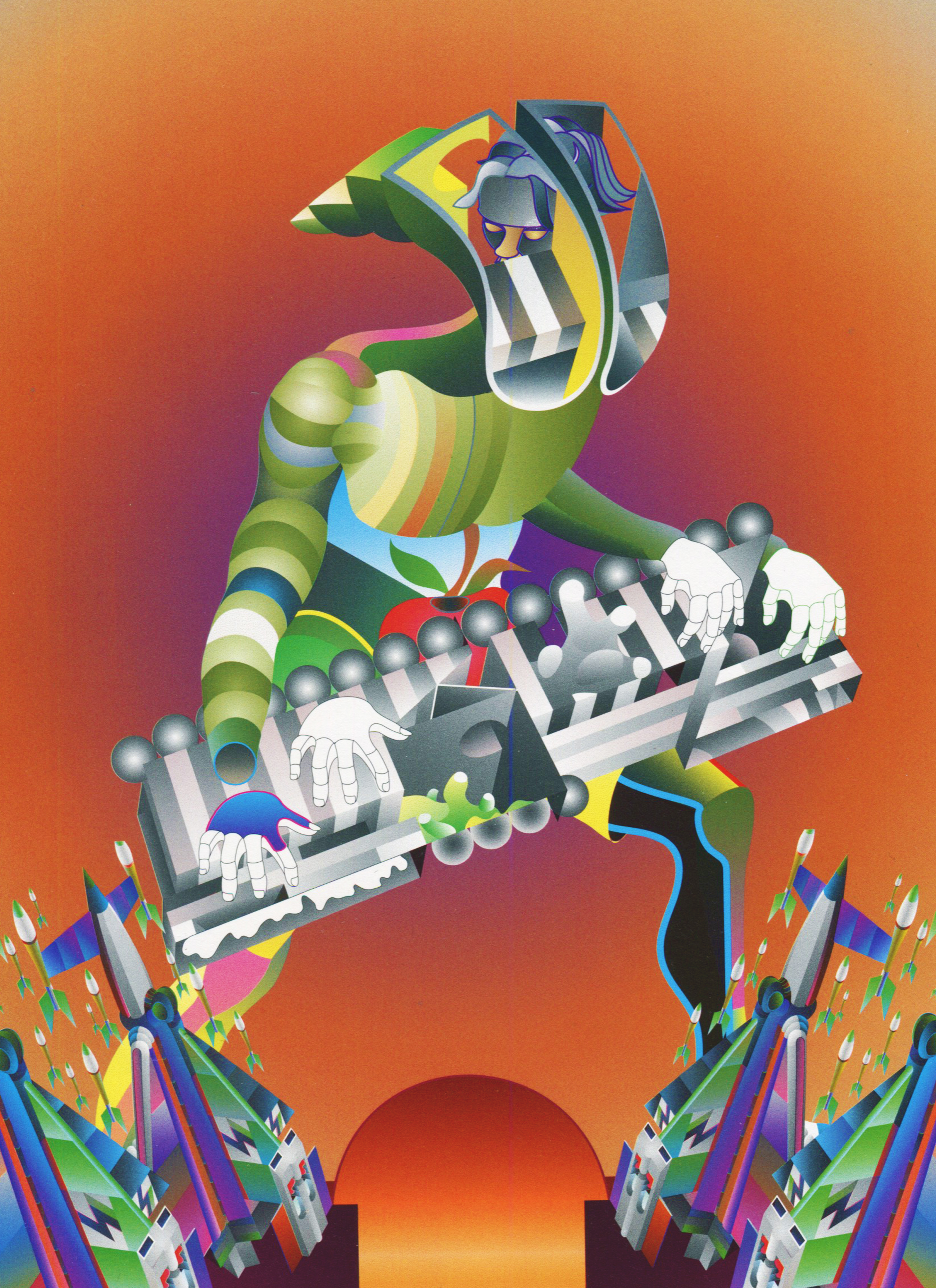

Written and illustrated by North Yorkshire design duo, Jan and Ted Arundell in 1995, The Ten Dimensional Maze was a dazzling display of state of the art computer generated graphics, dizzying in their intensity, with a non-linear storyline that follows the exploits of Whizkid and his wizard counterpart, Merlin, as they meander through vegetal domains and alchemical stews that bubble through the vacuum density, sprawling like troubadours across cybernetic meadows of proto-succulent meta-worlds.

Written and illustrated by North Yorkshire design duo, Jan and Ted Arundell in 1995, The Ten Dimensional Maze was a dazzling display of state of the art computer generated graphics, dizzying in their intensity, with a non-linear storyline that follows the exploits of Whizkid and his wizard counterpart, Merlin, as they meander through vegetal domains and alchemical stews that bubble through the vacuum density, sprawling like troubadours across cybernetic meadows of proto-succulent meta-worlds.

For some readers, The Ten Dimensional Maze will probably represent nothing more than a foray into the kitsch regions of psychedelia, but the book contains much more nuance.

Often times the term psychedelic doesn’t evoke the vision of it’s true meaning, partly due to the aesthetic of the visual counterculture of the 1960s and 70s, and how those cultural motifs are situated in the minds of future generations. In the true sense of the word ‘psychedelic’, the soul is manifest, evoking itself to glimpse into the trans-dimensional mystery machine - which is also you.

In the case of ‘The Ten Dimensional Maze’ the computer generated, flute playing shamans are analogous to the idea of deconstructing culturally sanctioned reality through the hyper-space of our technological mythos.

Thomas S. Kuhn (1922 - 1996), a physicist and philosopher of science from Harvard, is arguably most recognised for his coining of the concept ‘paradigm-shift’, which is by now common usage in the english language. His book, ‘The Strucutre of Scientific Revolutions’ highlighted the underlying matrix of ‘the paradigm’ that would inhibit the understanding and application of new discoveries until a cultural shift took place, enabling a re-examination of the scientific findings and intergrating them into a new mental framework.

A common theme can also be found in the work of media theorist Marshall Mcluhan, who’s work has succumbed ironically to the weight and historical abstraction of the print and electric mediums he so eloquently deconstructed.

Mcluhan stated that the use of language was a technology, or an ‘outering’ of inner thoughts. It was also suggested that all kinds of technological media were an extension of the human mind-body interface. Electricity being the extension of the nervous system, clothing an extension of the skin, the wheel an extension of the foot, the telephone an extension of the voice and so on, much in the same way Albert Einstein once wrote that “space is identical with extension, but extension is connected with bodies; thus there is no space without bodies and hence no empty space”.

Often times the term psychedelic doesn’t evoke the vision of it’s true meaning, partly due to the aesthetic of the visual counterculture of the 1960s and 70s, and how those cultural motifs are situated in the minds of future generations. In the true sense of the word ‘psychedelic’, the soul is manifest, evoking itself to glimpse into the trans-dimensional mystery machine - which is also you.

In the case of ‘The Ten Dimensional Maze’ the computer generated, flute playing shamans are analogous to the idea of deconstructing culturally sanctioned reality through the hyper-space of our technological mythos.

Thomas S. Kuhn (1922 - 1996), a physicist and philosopher of science from Harvard, is arguably most recognised for his coining of the concept ‘paradigm-shift’, which is by now common usage in the english language. His book, ‘The Strucutre of Scientific Revolutions’ highlighted the underlying matrix of ‘the paradigm’ that would inhibit the understanding and application of new discoveries until a cultural shift took place, enabling a re-examination of the scientific findings and intergrating them into a new mental framework.

A common theme can also be found in the work of media theorist Marshall Mcluhan, who’s work has succumbed ironically to the weight and historical abstraction of the print and electric mediums he so eloquently deconstructed.

Mcluhan stated that the use of language was a technology, or an ‘outering’ of inner thoughts. It was also suggested that all kinds of technological media were an extension of the human mind-body interface. Electricity being the extension of the nervous system, clothing an extension of the skin, the wheel an extension of the foot, the telephone an extension of the voice and so on, much in the same way Albert Einstein once wrote that “space is identical with extension, but extension is connected with bodies; thus there is no space without bodies and hence no empty space”.

“Though the world does not change with a change of paradigm, the scientist afterward works in a different world... What occurs during a scientific revolution is not fully reducible to a re-interpretation of individual and stable data. In the first place, the data are not unequivocally stable.” - Thomas S. Khun.

McLuhan’s theory of media places human thought in the same context as an alchemical conjunction, science as an extension of spirituality. Simply put, the environment is a reflection of what we communicate, our tools, or technologies for doing this, reveal not the nature of reality but the nature of the tools. All relational proximities are extensions of space, not simply how things appear but how things appear to be used. All of this constitutes the basic fabric of what we experience as a standardised ‘reality’.

McLuhan was also remembered for his 1964 phrase, the ’Global Village’, where he suggested that not only a connectedness of culture would be permitted through electricity, but that this would also reverse the relational meanings of certain ideas that mutated in the hidden psychological environments of the dominant technology. This idea came some forty years before our current understanding of online communication.

Our vocabulary for describing the use of computers and technology in general seems somehow tied to materialism. The opposite could be said for the psychedelic experience, as it rarely enters into constructive social discourse, nor is it usually taken seriously, perhaps becasue of it’s seemingly ineffable nature, its existence beyond language.

McLuhan was also remembered for his 1964 phrase, the ’Global Village’, where he suggested that not only a connectedness of culture would be permitted through electricity, but that this would also reverse the relational meanings of certain ideas that mutated in the hidden psychological environments of the dominant technology. This idea came some forty years before our current understanding of online communication.

Our vocabulary for describing the use of computers and technology in general seems somehow tied to materialism. The opposite could be said for the psychedelic experience, as it rarely enters into constructive social discourse, nor is it usually taken seriously, perhaps becasue of it’s seemingly ineffable nature, its existence beyond language.

These two worlds never seem to be reconciled, yet both worlds of material and non-material share many of the same constituents as the psychedelic and technological worlds. All are bound by the mythos of an ontological matrix - how we name things.

Computers, for example, are things of alchemical artifice whether they are material or phenomenological, with internal mechanisms powered by minerlas that reflect outward images via crystals, these machines have never been seperate from nature nor from alchemy.

Tantalum, a metal used in computers and smartphones, is named after a greek antihero who stole a gold dog from Olympus and boiled his son into a soup to gain a seat at the table of the Gods. As punishment for his arrogance, he was destined to stand in a pool of water under a fruit tree, with the water receding every time he tried to take a drink. The fruits on the tree were also just out of his reach. Its an absurd story, but also the origin of the english word ‘tantalising’, and describes how a supernatural, mineral to metal phenomena powers our electric relationship to communication and reality beyond the realms of physical pleasure and sustenance that nature seems to provide without much effort.

Computers, for example, are things of alchemical artifice whether they are material or phenomenological, with internal mechanisms powered by minerlas that reflect outward images via crystals, these machines have never been seperate from nature nor from alchemy.

Tantalum, a metal used in computers and smartphones, is named after a greek antihero who stole a gold dog from Olympus and boiled his son into a soup to gain a seat at the table of the Gods. As punishment for his arrogance, he was destined to stand in a pool of water under a fruit tree, with the water receding every time he tried to take a drink. The fruits on the tree were also just out of his reach. Its an absurd story, but also the origin of the english word ‘tantalising’, and describes how a supernatural, mineral to metal phenomena powers our electric relationship to communication and reality beyond the realms of physical pleasure and sustenance that nature seems to provide without much effort.

It is apparent that the origins of alchemy, psychedelia, computers, language and all other technologies throughout history have shared a common birthplace in the esoteric, but it is mainly our description that renders them separate. The late scientist and Ethnobotanist, Terence McKenna once asserted that we can look at the whole thing as a factory of moving mechanical parts. “The DNA is being read, the databases are being created and the protocols for moving through them are permissions to a new level of intelligence. The only difference between computers and psychedelics, is that one is easier to swallow. The Internet and computers are actually made from materials of the earth... silicon, glass, copper, gold, and silver. These are the things that the alchemist dreamt of. They transform space and time, they allow us to speak at a distance, and they allow us to wander through libraries thousands of miles distant. They make it so that no fact is too obscure and no person so hidden that you can’t reach them.”

As we delve further into our social psychologies in these perpetually obscure political and economic times, the one notable difference is that our mental tribalism has emerged through our metal connectedness. But since there is compression with every expansion, the cautionary element of this story will be revealed in our ability to navigate the unseen networks, the vast subterranean river systems and turbulent waves of information that offer only a tantalising mess of images.

As we delve further into our social psychologies in these perpetually obscure political and economic times, the one notable difference is that our mental tribalism has emerged through our metal connectedness. But since there is compression with every expansion, the cautionary element of this story will be revealed in our ability to navigate the unseen networks, the vast subterranean river systems and turbulent waves of information that offer only a tantalising mess of images.

“A radical phenomenon in science will be repeatedly treated as an anomaly until a new theory can explain it.” - Thomas S. Khun.

Further Reading ︎

Buy the book, The Ten Dimensional Maze

The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, Thomas S. Kuhn